Transforming Deviation ManagementTransforming Deviation Management

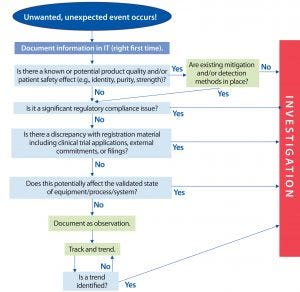

Figure 1: Overview of proposed two-tier process

All biopharmaceutical companies espouse a belief in scientific, risk-based approaches. However, with respect to deviation management systems (DMSs), the industry is falling short of that promise. By and large, companies still use a small-molecule pharmaceutical compliance model that dates back to the 1980s, based on the strategy that all deviations are created equal and require 30-day closure. Most bioprocessors still hold to a default 30-day rule, even though there is no specific regulatory requirement for that time frame. Major or critical investigations often take 50–60 days or longer, and simpler events can be closed much faster. The 30-day rule is not risk-based, and it can drive the wrong behaviors by promoting a check-the-box mindset and creating pressure to close an investigation without finding the true systemic root cause.

Some attempts have been made to improve on the above model, although most companies have tweaked their systems using the same formula: “deviation leveling.” Some have shifted away from a 30-day rule in favor of 45 or 90 days for more complicated issues. However, realizing the promise of a risk-based model requires more than just tinkering with the existing paradigm. Managers can’t pat themselves on the back for categorizing nonconformances as minor–major–critical or level 1–2–3 and still investigate all of them (even if to a limited extent).

Each company has faced a nebulous grey area with the minor deviations, which account for the largest volume of work. The approach to such events has been characterized as limited root-cause analysis (“RCA light”). Comparisons of many companies’ practices have shown that “minor” issues suffer from scope creep because once investigators start down their path, it is challenging for them to obtain stakeholder agreement on where to stop. Similarly, what does the third level mean? What is the real difference between “major” and “critical?”

By asking people to conduct check-the-box “investigations” for every minor deviation, companies unintentionally instill an overreliance on basic tools such as 5-Whys, PEMME (personnel, equipment, method, materials, environment), and fishbone diagrams. They run the risk of losing the point regarding why deviation management is performed — to find and fix problems — and replaced it with lengthy documents for nonissues that can’t or won’t be fixed.

The result is an overfilled “deviation warehouse” with rudimentary investigations that do not drive real improvement or preventive actions for operations groups. How often have you read a multipage deviation for a missed signature that made statements such as “Training records were reviewed, and personnel were current on the good documentation practices standard operating procedure (SOP),” or “The document was reviewed and found to be clear and concise.” Such formulaic approaches do little to help companies understand minor slips/lapses in their well-trained, well-intentioned employees. Nor do they enhance product quality or assure patient safety, which must be the primary goal.

Achieving the promise of a risk-based approach requires that investigators ask themselves one fundamental question: “Is this an event from which we need to learn lessons and make corrections, or is the risk low enough that we can tolerate a potential recurrence?” In a perfect world, we would prefer that no deviation ever recurs, but the desire that nothing ever should go wrong can hold companies back from taking a truly risk-based approach.

Figure 2: Potential decision tree

In April 2016, the BioPhorum Operations Group (BPOG) established its Deviation Management Systems workstream. With representatives from 16 major biomanufacturers (including the authors of this article), the team has developed and tested methods to separate nonconformances into two classifications: events or investigations. In this model, events are tracked and trended with documentation only if key attributes, and investigations are fully evaluated for root causes (Figures 1 and 2). A two-tiered approach might seem too rigid, but it is necessary to separate the wheat from the chaff. Either you investigate or you don’t; trying to have it both ways causes waste in existing systems. A transformation from current predominant models will require operational discipline to hold true to the new vision.

Companies need to eliminate time wasted on low-risk events, not just reduce it with “RCA light.” Doing so will enable trained and qualified investigators to develop more effective tools, techniques, and competencies for comprehensively evaluating causal factors and systemic issues involved in significant events. That allows companies to allocate resources much faster and dedicate teams to use more advanced RCA tools on true investigations, or use continuous improvement strategies on trends that will help them learn from important issues — ultimately leading to more effective corrective and preventive actions (CAPAs).

A good investigation hinges on what information is gathered and how it is gathered: as close to the event as possible — ideally as the event is occurring. Freeing up capacity to shorten the gap between event occurrence and advent of an investigation improves line-of-sight CAPAs and increases the likelihood of effective results. Moving investigations to manufacturing shop floors with the right cross-functional support — e.g., dedicated professional investigators and quality assurance (QA) — will decrease the time it takes to investigate while increasing the amount of usable information obtained. Ultimately, that builds smarter investigations.

If you asked, “But wouldn’t that approach take on too much risk?” We would counter that companies already tolerate risk associated with minor deviations by not taking a preventive action for every one. In the end, retraining and adding details to a SOP doesn’t really solve a problem. So if you are comfortable with continuing to operate knowing that people will occasionally make documentation errors or perform steps incorrectly, or that single-use parts leak sometimes, then there is little value in investing resources to investigate these issues unless they trend upward.

Stated simply, the level of effort being put into current processes is commensurate neither with the risk they represent nor with the value they deliver. Consider the data below, gathered from a survey of 13 BPOG member companies:

Most deviations (72%) were classified as minor — and 28% as major or critical — with each site averaging ~1,500 deviations annually.

Almost all deviations (98%) are investigated, with little or no tracking or trending — in other words, no risk-based selection of what should and should not be investigated.

About two-thirds (60–70%) of deviations have no effect on product quality or patient safety.

Minor deviations involve ~18.1 hours of activity time, 5.3 hours of which is spent by operations staff involved in investigations (time they are not spending making product).

Minor deviations take ~29 calendar days to complete.

About 24% of all deviations are deemed “repeats,” indicating an ineffective CAPA process or lack of CAPA actions taken.

QA professionals surveyed are convinced that they could make a major difference with the new DMS described herein— freeing up significant amounts of time for proactive, preventative work on the manufacturing floor.

A Proposal for Transforming Deviation Management

If tinkering hasn’t worked, then how does the industry move to a new state? What will that look like, and how will it work in practice? The BPOG workstream’s proposed system is based on three main tenets: Stop investigating for causes of low-risk events. Create an open-reporting culture. Monitor with a robust trending program to identify rising issues before they become major events.

The goal of a reenvisioned DMS is not to ignore minor issues or engage in blind pursuit of lean manufacturing for its own sake. Rather, it is an intentional shift in problem solving to drive the right CAPA actions and ultimately increase “right first time” for manufacturing batches.

The redesign was driven by a recognition that different types of nonconformances are best solved using different investigational techniques. For minor, low-risk events, companies should document the reasons for that classification and key facts/metadata that are immediately available to support trending. That should apply to an estimated 60–70% of all deviations. Such events generally are symptoms of larger systemic process issues. Rather than conducting a comprehensive root-cause analysis on each individual instance, however, experienced investigators have found that these issues are addressed more effectively by trending for patterns and using continuous improvement methodologies to address “common-cause” issues. More significant issues and deviations, however, are likely to result from “special-cause” issues — and thus are best investigated using traditional root-cause analysis methods.

The workstream team believes that a robust DMS can be achieved only by embracing an open reporting culture. The goal is to uncover potential issues and near-misses proactively because they can remain unseen otherwise until they are uncovered during an investigation process — after something significant already has gone wrong. A reactive approach does not help build quality into bioprocesses.

Learn from Trends: Each nonconformance, whether it is a minor event or a batch-ending deviation, provides an opportunity for a company to learn more about its processes, equipment, and staff. However, it is equally important to realize whether that learning is better from a specific event (e.g., contamination, out-of-specification (OoS) result, or major equipment failure) or from a pattern of issues (e.g., minor documentation discrepancies isolated to one department or shift). Using a single database to capture all learning opportunities and events enables continuous improvement by highlighting such opportunities while they are still small and before they become significant deviations. A fully realized, open reporting model also would end the perennial debate over whether something is an investigation or “just a comment.” That often keeps minor issues out of sight, buried in archived forms and batch records — or worse yet only in people’s memories. From a practical standpoint, however, a simple approach to handling track-and-trend events is a crucial prerequisite to prevent hampering the overall system.

Managers can provide support by promoting a questioning attitude in their staff and empowering employees to report issues, flaws, and workarounds that they live with every day. Because frontline workers are closest to a process, they are in the best place to identify the problems as well as fixes that will allow easier and more efficient operations. Empowerment of frontline personnel to be involved in real-time problem solving with the proper tools, training, and support fosters a culture that values intellectual diversity. Such a culture gives companies the best chance to learn from events and implement CAPAs that indeed will reduce risk of future occurrence. In addition, it closes the feedback loop to the frontline and further promotes trust in the open reporting system. Too often these days, individuals who initiate deviations don’t know the outcome or learnings of the resulting investigations.

Tracking and Trending

An essential element in the future-state DMS is to have a robust trending program that analyzes data for in-aggregate system defects. The foundations of this concept exist already at most companies: Good investigations include trend review for each specific issue/cause, and many companies conduct a retrospective review when triaging deviations. The proposed trend program builds on that foundation to look holistically at event patterns.

The first step is capturing the right data/metadata that describe a given event, but not necessarily its cause. This begins with having solid categorization for types of events: e.g., critical and noncritical parameters out of range; equipment malfunction and in-process leaks; compromised samples; and out-of-trend (OoT), out-of-limit (OoL), and OoS results. Beyond that, basic data alone often support an understanding of whether a trend is in progress. In failures of single-use components, for example, the data required might include part number, batch number, and failure mode (e.g., seam tear, puncture, crack, or cut). For a human-error event, those data could include shift, whether shift handover was involved, and other tasks or activities going on at the time. Naturally, dates, departments, document and batch numbers, and the like will be continued to be gathered. All of this information is readily available at the time an event occurs or is discovered.

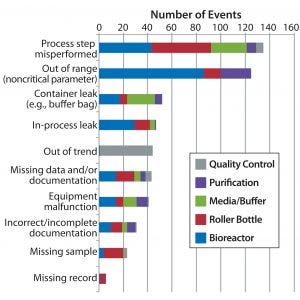

Figure 3: Example trending tools — Pareto analysis of top event categories by department

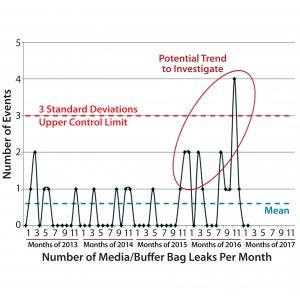

After event data are collected, records should be closed as soon as possible so that resources can be made available for other work. One such task is trend analysis, which should be conducted regularly. The workstream team recommends beginning with monthly departmental trend reviews and slightly longer intervals for site-level reviews or those covering plant networks. Trend analysis should be owned by related functional areas to help those teams understand the biggest pain points or improvement opportunities for their functions. Data can be evaluated by simple Pareto analysis (Figure 3) to identify what types of events are the biggest nonconformance contributors. Over time, control charts (Figure 4) can be developed for certain types of events that a company can anticipate to occur — e.g., documentation errors or single-use failures — to establish whether things are within a state of control.

Figure 4: Example trending tool — media buffer bag leak control chart

The goal of this DMS transformation is not to replace unneeded investigations with unneeded and unwieldy monthly reports. Although some level of formal management review is warranted, it should be aligned with a given site’s quality management review process. At shorter internals, trend reviews are a natural fit for the “managing for daily improvement” (MDI) boards that have become increasingly common throughout the biopharmaceutical industry. A quick update with visualized data at MDI daily meetings with shop-floor personnel should be an effective way to identify actions to address the biggest contributors. That could mean launching a trend investigation into an issue that has not yet escalated, or it could lead to an alternative continuous improvement project to conduct a Kaizen/5S activity or enhancement process to prevent failures.

The health of a new DMS system could be measured easily by establishing key performance indicators related to time-to-closure for both track-and-trend events and investigations, the ratio of events to investigations, and how many actions are taken on top contributors identified by trend analysis.

Tracking Low-Risk Events |

|---|

Examples of low-risk events suitable for tracking and trending: |

Modernizing to Work Smarter

The proposed future state for DMS balances inherent tension between velocity and capacity of deviation systems with thoroughness of learning from events. Furthermore, this is more than a strawman model. Elements of it have been implemented in full by BPOG members, and other member companies see it as the next step in a deviation maturity model. The natural consequence of both an open reporting system and a truly risk-based approach is that more events will be initiated — but actual investigations will be concentrated to only those representing true risks for bioprocesses and patients. Ultimately, this deviation management structure promotes an open reporting of unexpected events, ends debate on whether to investigate, and generates more meaningful data showing what is truly occurring on manufacturing plant floors.

In an age of “big data,” an open reporting system builds a cumulative set of system defects for companies to learn from and gives managers a better view on the health of their plants. By freeing up valuable resources from overanalyzing each and every minor issue, teams can unleash their skills faster and more effectively on significant nonconformances and trends of minor issues. Proactively learning about both types of deviations provides the most effective means to driving solutions and eliminating recurrences.

Some managers may be concerned about how to defend this approach to regulators. However, early adopters of the model have had successful inspections from multiple authorities. Furthermore, events that typically interest inspectors the most are not minor issues; they know companies are going to make mistakes and have problems. Regulatory authorities care the most about how the biopharmaceutical industry investigates its large issues, how it addresses recurrent issues, and how quickly it transfers solutions to manufacturing groups to eliminate both. The proposed DMS system is designed to improve all three of those lines of investigation, which should make questions about investigative processes easy to answer.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge Jennifer Karatka (human performance manager at Pfizer) for peer reviewing this manuscript and also the other 13 companies implementing the consensus approach set out herein.

Corresponding author Brian Chviruk is associate director of PTS investigations at Shire, c/o BPOG 5 Westbrook Court, Sharrowvale Road, Sheffield S11 8YZ UK; [email protected]. Ewald Amherd is head of quality customer engagement at Lonza Ltd; Joseph J. Antonetti is associate director of SQO R&D at Sanofi; Philippe Verdon is quality unit director at Merck Serono SA; and Amanda Patnaud is QA senior supervisor at Biogen Idec.

You May Also Like