A New Kinetic Structured Model for Cell Cultivation in a ChemostatA New Kinetic Structured Model for Cell Cultivation in a Chemostat

Mathematically modeling the kinetics of batch and continuous cultivation allows you to not only calculate and evaluate the effects of process parameters, but also to forecast those parameters and duration of cultivation to develop a cost-effective production process. Mathematical modeling microorganism cultivation was intensively developed in the second half of the last century.

Equations 1–6: ()

Monod proposed

Equation 1 for batch processes in 1942 (1). In that equation, µ and µmax are the specific and maximum growth rates, respectively (h−1), S is the substrate concentration, (g/L), and KS denotes a Monod semisaturation constant (g/L). That model implies that yield Y is a constant value. For continuous-mode cultivation (e.g., chemostat), Y can be calculated using

Equation 2, in which X is the biomass concentration (g/L), and S0 is the limiting substrate concentration in the input (g/L). For a continuous cultivation at flow rate D (h−1), combined solution of

Equations 1 and

2 gives the equation called a Monod model for chemostat cultivation under full stirred conditions and substrate limitation. For the biomass, this is

Equation 3, and for the limiting substrate it is

Equation 4.

PRODUCT FOCUS: RECOMBINANT PROTEINS

PROCESS FOCUS: PRODUCTION

WHO SHOULD READ: PROCESS DEVELOPMENT AND CHARACTERIZATION

KEYWORDS: KINETICS, PERFUSION, SIMULATION, MODELING, FERMENTATION, OPTIMIZATION

LEVEL: ADVANCED

In 1959, Luedeking and Piret (2) presented a model describing cell cultivation to produce valuable metabolites. Moser (3) in 1958 and Andrews (4) in 1968 both described models for continuous processes, taking into account substrate inhibition as an example of trying to resolve some limitations of the Monod theory. Their work is shown as

Equations 5 and

6, in which K* denotes a new parameter not considered in

Equation 1, provided that K* > 1, and Ki is the inhibition constant.

Equations 1–6:

Equation 1

Equation 2

Equation 3

Equation 4

Equation 5

Equation 6

The improved Monod equation and kinetic models on its base describe biomass growth and formation of target products gave rise to various stochastic, unstructured, and structured models, which Gormely reviewed in detail in 1973 (5). Pirt (6), Bailey and Ollis (7), and Terskov and Gurevich (12) presented the classification and critical analysis of the developed kinetic models. Some studies have linked process kinetics to the physiological state of cells and to the concentration of substrates consumed for biomass growth and maintenance of population viability (8,9,10,11)(13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24).

Here we discuss the method of structuring a cell population into dividing and nondividing cells of zero age. We describe universal laws deduced mathematically and show graphically the types of static characteristics of continuous-mode cultivation X = ƒ(D). The Monod equation and the other well-known models are the particular cases of our proposed model. In addition, we provide some discrepancies of the proposed method from the Monod model:

Extreme dependence of a specific growth rate on substrate concentration implies a maximum specific growth rate, which differs from the results obtained from the Monod equation.

Specific growth rate depends on inhibitory metabolite concentration, which differs from the propsed model.

The proposed model describes energy (oxygen) limitation when the concentration of substrate (oxygen) is very low due to its extremely low solubility. The Monod model and others do not consider such a case.

Equations 7–14:

Equation 7

Equation 8

Equation 9

Equation 10

Equation 11

Equation 12

Equation 13

Equation 14

Materials and Methods

Our previous structured approach for calculating the model and to control batch processes is based on two differential equations for biomass growth inhibition phase (GIP) (13,14,15,16). For the biomass,

Equation 7 applies. In that equation, n is the integer, an order of the derivative of the function; Xdiv is the quntity of dividing cells; Xst is the qauntity of nondividing (stable) cells; K is a product of overall growth rate and the rate of accumulation of stable or nondividing cells; A is the ratio of maintenance energy to the energy consumed for biomass growth or a specific rate of accumulation of stable or nondividing cells.

Furthermore, C = 1 if n = 1, and C = 0 if n ≥ 2.

For the target product (substrate),

Equation 8 applies. In that equation, P is the target product, S denotes the limiting substrate, kdivP,S (h−1) and kstP,S (h−1) are the product and substrate constants of dividing and nondividing cells, respectively.

To get a generalized model of the chemostat, we will use equations for the total amount of biomass in GIP, a share of nondividing cells (R = Xst/X, in which X is the total biomass for GIP), changes in the number of nondividing cells and their share XstR at the end of logarithmic growth phase (LGP), and a specific rate of product formation and substrate consumption (

Equation 8). This is

Equation 9, in which q is defined by

Equation 10.

Yield is determined by

Equation 11. In a steady state, flow rate is equal to the specific growth rate (

Equation 12) (1,2,3,4,5,6).

Under equilibrium conditions,

Equations 9 and

10 may be equated. Then multiplying the left and right sides of the equation for Y (

Equation 11), we obtain the final equation for the dependence of flow rate on the number of nondividing cells and yield (

Equation 13). As we show below,

Equation 13 represents a generalized equation. It combines all the cases of culture behavior in all flow processes, and describes all deviations from the Monod model.

Clearly, there are no limits for exponential cell growth. The rate of substrate consumption is maximum and is expressed by kdiv, provided that maximum specific growth rate µmax follows

Equation 14. In such case, it is impossible to control the chemostat, and biomass concentration in the stationary growth phase may take any arbitrary value (7).

Equations 15–23:

Equation 15

Equation 16

Equation 17

Equation 18

Equation 19

Equation 20

Equation 21

Equation 22

Equation 23

If growth rate is limited by some substrate, then nondividing cells must appear in the system. Such cells possess a limiting substrate consumption distinctive rate kst that affects the static characteristics. Previous studies showed that nondividing cells can be formed at the end of LGP during batch fermentation (13,14,15,16). We show below that this very phenomenon accounts for the observed deviations from the Monod model and is expressed in the absence output of microorganisms predicted by the Monod model when the rate of dilution D is equal to or significantly higher than µmax. So, we must examine cultivation at D ≥ µmax and D < µmax. In previous studies (13,14,15,16), we used

Equations 15–

17 for R at the end of LGP and GIP. In those equations, X denotes the total biomass concentration in the batch process, and X1 (defined by

Equation 16) is the biomass concentration at the beginning of population structuring.

Equations 15 and

17 correspond to D ≥ µmax and D < µmax, respectively.Parameters X(D→0) and XDmax correspond to parameters Xp and XLim, respectively during batch fermentation in the chemostat. The values of X(D→0) are always greater than those of XDmax for all types of static characteristics (such as D < µmax), except for “endogenous metabolism” characteristics (9) for which X(D→0) < XDmax. Substitution of

Equations 15 and

17 into

Equations 13 and

15 shows the dependence of flow rate D on the equilibrium concentration of the biomass X for cases in which D ≥ µmax and D < µmax. The results are

Equations 18 and

19.

If the left and right sides of

Equation 18 are multiplied by X, and

Equation 19 is converted to ((D – Ykdiv)*X)−1 = ƒ(X), and both sides of the resulting expression are divided by X, then the resulting equations (

20 and

21) of the structured model determine static characteristics of the chemostat.

If dependencies of the experimental data are built according to

Equations 20 and

21 in the coordinates (D – Ykdiv)*X = ƒ(X−1) and ((D – Ykdiv)*X)−1 = ƒ(X), then it would be possible to work out all the parameters of the chemostat structured model. Parameters µmax, Y, S0, XLim, Xp, A, and K/A2 can be determined first in the batch process. The points of those graphical dependencies, which are described by relevant laws, should be well grouped around a straight line. Deviations from the straight line indicate the action of one of the above lows. Common chemostat models represent static processes as a function X = ƒ(D). So,

Equations 20 and

21 have been converted in accordance with a generally accepted view. For D ≥ µmax and D < µmax, these equations appear, respectively, as

Equations 22 and

23. In

Equation 23, X1 has a positive (+) solution to match the Monod model, and X2 has a negative (-) solution for cultures with “endogenous metabolism” in compliance with results from Bailey and Ollis (7).

Equation 19 can be used to calculate a low boundary of the chemostat operating range (the admissible value D at which the equilibrium concentration of the biomass will be guaranteed to match the values of X being set by the proposed chemostat model). For the static characteristics of the type D ≤ µmax, this value corresponds to D = Ykst. Using

Equation 23, you can determine the equilibrium concentration of biomass X for the upper boundary of the permissible flow rate in the chemostat, when D ≤ µmax, at D = µmax. The former value is optimal in terms of biomass as a target product because it ensures maximum productivity. In practice, it often happens that when D = µmax, equilibrium biomass concentration X = 0.5X(D→0), lower as it was shown in the example of “Conformity with the Monod model” (Table 1). As a rule, any deviation from the boundaries of the determined range can lead to uncontrollable changes in the equilibrium states. However, remember that the state D = µmax is impossible in all processes. To control such processes, the parameter concentration S0 in the input flow, should be taken into account. Also, the quality of the nutrient medium composition should cause concern because possible growth inhibitors may be present in it.

Table 1: Model parameters and significant factors for the calculation of various types of static characteristics

Table 1:Q

94;Model parameters and significant factors for the calculation of various types of static characteristics ()

Results and Discussion

Equation 13 as a Generalized Model with respect to Earlier Models: In the proposed model described by

Equations 13,

22, and

23, the main determining factors in the system under equilibrium conditions are constants of substrate use by appropriate cell groups as well as the relative number of nondividing cells R both in the steady state and in the initial batch culture. This model allows for better understanding and control of the essential elements in continuous processes. The essence of the chemostat state is that the derivative of the dividing cells with respect to nondividing cells is a fixed constant for any a specific value D. That is a more reasonable and precise condition than that of

Equation 12, because if D > µmax (as it was deduced in generally accepted models such as the Monod model), then culture process management is impossible, and the situation itself is by no means explained. Table 1 lists examples of possible static characteristics of continuous cultures that describe and explain the structured chemostat models (

Equations 22 and

23) at a qualitatively new level. It is important that the Monod model can be derived from the general model (

Equation 13, assuming that D ≤ µmax), provided that the equation is reduced to a common denominator and

R is substituted fromEquation 17

X fromEquation 4 replaces S

it is assumed that S << S0.

That simplification leads to

Equation 24. In that equation, taking into account S << S0 in the denominator, the values X(D→0) – YS0 and YS are comparable. So, the value S in the expression in brackets in the denominator and numerator can not be equated to 0. The first two terms in the numerator represent the sum of the constants, and if its sum is much less than the third term in the numerator containing multiplier S, then it can be equated to 0. In this case, for the first two terms in the numerator

Equation 25 is true.

Reduction of both the numerator and denominator in

Equation 24 by S0Y2, replacement of D for µ, and use of

Equation 12 leads to

Equation 26. That equation is fully consistent with the Monod

Equation 1, in which the constant KS is defined by

equation 27.

Equations 24–31:

Equation 24

Equation 25

Equation 26

Equation 27

Equation 28

Equation 29

Equation 30

Equation 31

Similar to the deductions of the Monod model, using

Equations 12 and

14 to make the appropriate substitutions in

Equations 20 and

21 and simplifying the deduced ratios results in a model of the dependence of specific growth rate on the substrate concentration proposed by Pirt 6, shown as

Equation 28. In that equation, µ0 is the specific growth rate at zero concentration of the substrate, and the specific rate (µ0 + µ1) is reached when S→∞. If

Equation 17 is substituted into

Equation 21, then by rearranging terms and reducing the known small values that contain the parameter S2 and the constant K, we form an equation that is formally identical to the Pirt model for specific growth rate. Using the obtained equation KS, µ0, and µ1 can be defined as

Equations 29–

31. Those equations — which are similar to those of Moser (

Equation 5) and Andrews (

Equation 6) — can be deduced from

Equation 13 for the structured model. An equation for the processes of product inhibition — such as the Ierusalimsky model (12) — can be similary deduced.

When applying this method, you should remember that it describes static characteristics, which are essentially a set of various processes running at different rates D. For continuous-mo

de cultivation, it is correct to say that D→0 rather than D = 0, because a simple substitution of D = 0 in the equation for the “flow” model does not mean that equations for batch processes can be automatically obtained in this way. Thus, the proposed continuous-mode cultivation model is based on the subdivision of the microbial population into dividing and nondividing cells of zero age. The model takes into account different rate constants for the consumption of a limiting substrate and constants for a biomass. It also explains the well-known phenomenon of chemostat behavior deviation, which has not been described precisely by mathematical methods (12) that made cultivation control of microbiological processes impossible. Our proposed mathematical model of the chemostat will help to change the situation.

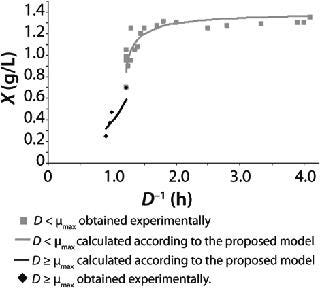

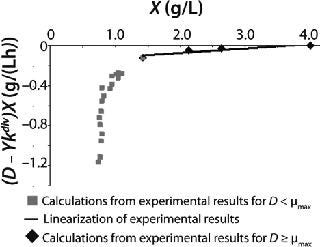

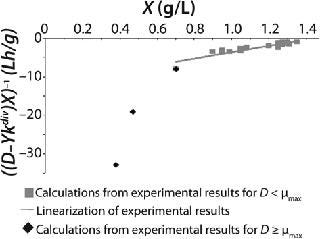

Examples of Calculations of Various Static Characteristics from

Equations 21–

23: Table 1 lists the model parameters and significant factors for the calculation of various types of static characteristics. Figure 1 shows the literature data (7) for calculating a continuous process for Aerobacter cloacae and the corresponding curves calculated from the shown models. Table 1 shows the the data as “Conformity with the Monod model” and “Deviation 1 from the Monod model.” We calculated the parameters of those models after constructing dependences shown in Figures 2 and 3, specified in Equations (

21 and

23) and (

20 and

22), respectively for each case.

Figure 1: ()

Figure 2: ()

Figure 3: ()

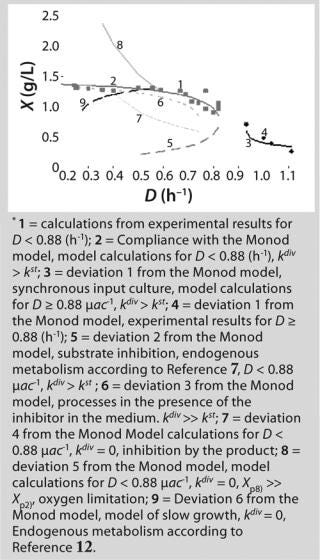

Table 1 shows the parameters for other possible types of static characteristics of continuous cultures analyzed in detail in a previous study 12,. Table 1 and the legend of Figure 4 (numbers 2–6) show the deviations from the Monod model. We arbitrarily set Model parameters for such deviations (except for deviation 2, for which we used the parameters of the curve for “Conformity with the Monod model” and a “–” sign for the solution). The only condition was that the shape of the derived characteristics would strictly conform to the shape of the curve presented in reference 12,. Table 1 also shows the significant factors (“+” or “–” sign) that we used to solve

Equation 23 and construct Figure 4.

Figure 4: ()

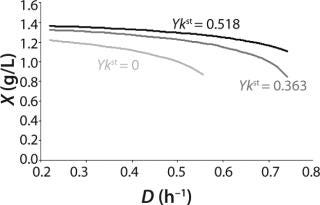

Figure 5 shows the decrease of the static characteristics for different kst values at constant kdiv for D ≤ µmax, as frequently encountered in microbiological practice. In all those examples, Y = constant. The calculation of the relevant characteristics of the substrate is not difficult. For all subsequent examples, the constant yield is used on the default. Therefore, experimental results comply with model data.

Figure 5: ()

Our Proposed Model

We propose a new mathematical model for cell cultivation in a chemostat. Our model is based on the structuring of the biomass into two main groups: dividing and nondividing cells. The model is applicable both to existing static characteristics such as the Monod model and to the deviations from it.

We determined the range of chemostat stability at the specified flow rate D and concentration of the input limiting substrate S0. We also proposed the methods for determining parameters of the chemostat structured model.

The value of the derivative of dividing cells to nondividing cells of zero age is constant for a given flow rate. That value is no less important than the equality of specific growth rate and nutrient flow rate, which determines the equilibrium of the chemostat.

We showed that the corresponding specific rate constants of limiting substrate use by dividing and nondividing cells determine the system equillibrium. We also demonstrated that the new proposed structured model of the chemostat is more general than any other existing model. In each specific case, the model provides comparable equations to the well-known models of Monod, Pirt, Moser, Andrews

, and Ierusalimsky.

About the Author

Author Details

Sergey P. Klykov, PhD is senior researcher, and corresponding author Vladimir V.Kurakov, PhD is general manager of biotechnology at PHARM-REGION, Ltd. 10/1, Baryshikha Street, Moscow, Russian Federation 125222; +79037951745; [email protected].

REFERENCES

1.) Monod, J. 1942.Recherches sur la Croissance des Cultures Bactériennes2nd Edition, Hermann and cie, Paris.

2.) Luedeking, R, and EL. Piret. 1959. A Kinetic Study of the Lactic Acid Fermentation: Batch Process at Controlled pH. J. Biochem. Microbiol. Tech. Eng 1:393.

3.) Moser, H. 1958.The Dynamics of Bacterial Populations Maintained in the Chemostat, Carnegie Institute, Washington.

4.) Andrews, JF. 1968. A Mathematical Model for the Continuous Culture of Microorganisms Utilizing Inhibitory Substrate. Biotechnol. Bioeng 10:707-723.

5.) Gormely, LS. 1973.Continuous Microbiological Leaching of a Zinc Sulphide Concentrate, University of British Columbia, Vancouver.

6.) Pirt, SJ. 1975.Principles of Microbe and Cell Cultivation, Blackwell Scientific Publications, Oxford.

7.) Bailey, JE, and DF. Ollis. 1977.Biochemical Engineering Fundamentals, McGrow-Hill Book Co, New York.

8.) Tsuchiya, HM, AG Fredrickson, and R. Aris. 1966. Dynamics of Microbial Cell Populations. Advan. Chem. Eng 6:125-206.

9.) Fredrickson, AG, and HM. Tsuchiya. 1963. Continuous Propagation of Microorganisms. AIChE J 9:459-468.

10.) Eakman, JM, AG Fredrickson, and HM. Tsuchiya. 1966. Statistics and Dynamics of Microbial Cell Populations. Chem. Eng. Progr. Symp. Ser 62:37-49.

11.) Rumkrishna, D, AG Fredrickson, and HM. Tsuchiya. 1967. Dynamics of Microbial Propagation: Models Considering Inhibitors and Variable Cell Composition. Biotechnol. Bioeng 9:129-170.

12.) Terskov, IA, and YL. Gurevich. 1975.Characteristic Features of Continuous Culture of Microorganisms as the Object of Control in Application of Mathematical Methods in Microbiology Center for Biological Research, AS of the USSR, Pushchino.

13.) Klykov, SP, and VV. Derbyshev. 2003.Relationship between Biomass Age Structure and Cell Synthesis, Sputnik-Company:.

14.) Derbyshev, VV, and SPA. Klykov. 2003.Technique for Cultivation of Cell Biomass and Biosynthesis Target Products with Specified Technological Parameters, Patent of Russian Federation 2228352.

15.) Klykov, SP, and VV. Derbyshev. 2009. Dependence of the Age Structure of Cell Population, Consumption of Substrate, and Product of the Synthesis on Energy Consumption. Biotechnologia 5:80-89.

16.) Klykov, SP. 2011. A Cell Population Structuring Model to Estimate Recombinant Strain Growth in a Closed System for Subsequent Search of the Mode to Increase Protein Accumulation during Protealysin Producer Cultivation. Biofabrication 3:12.

17.) Bouguettoucha, A. 2010. Improved Growth Model for Two-Stage Continuous Cultures of Lactobacillus helveticus. Electronic J. Biotechnol www.ejbiotechnology.info/index.php/ejbiotechnology/article/view/v13n5-16 13.

18.) Zeng, AP. 1995. A Kinetic Model for Product Formation of Microbial and Mammalian Cells. Biotechnol. Bioeng 46:314-324.

19.) Znad, H. 2004. A Kinetic Model for Gluconic Production by Aspergillus niger. Chem. Pap 58:23-28.

20.) Wang, X. 2006. Modeling for Gellan Gum Production by Sphingomonas paucimobilis ATCC 31461 in a Simplified Medium. Appl. Environ. Microbiol 72:3367-3374.

21.) Bajpai, RK, and M. Reuss. 1980. A Mechanistic Model for Penicillin Production. J. Chem. Tech. Biotechnol 30:332-344.

22.) Constantinides, A. 1970. Optimization of Batch Fermentation Processes: Development of Mathematical Models for Batch Penicillin Fermentations. Biotechnol. Bioeng 12:803-830.

23.) Weiss, R M, and DF. Ollis. 1980. Extracellular Microbial Polysaccharides: Substrate, Biomass, and Product Kinetic Equations for Batch Xanthan Gum Fermentation. Biotechnol. Bioeng 22:859-873.

24.) Dhanasekar, R, T Viruthagiri, and PL. Sabarathinam. 2003. Poly (3-hydroxy butyrate) Synthesis from Mutant Strain Azotobacter vinelandii Utilizing Glucose in a Batch Reactor. Biochem. Eng. J 16:1-8.

You May Also Like