Voices of Biotech

Podcast: MilliporeSigma says education vital to creating unbreakable chain for sustainability

MilliporeSigma discusses the importance of people, education, and the benefits of embracing discomfort to bolster sustainability efforts.

As organizations launch operational excellence (OpEx) programs, they are faced with challenges that must be overcome before they can achieve true excellence. One of the largest barriers to overcome is employee perception. The first step is to provide training that will energize employees and change their understanding of what operational excellence can do for them and their organization. For this reason, Bayer has developed an OpEx fundamentals training that starts with the “heart and mind,” focusing on less-threatening “soft skills” first and thus opening an audience to listening to the message the team is trying to convey.

Our training also focuses on neurolinguistic programming (NLP) and Lewin’s change model. This helps remove misperception and retrains thought development so employees can eliminate false perceptions and replace them with new understanding and openness to operational excellence. Although team members are not instantly converted, the process of change is triggered so that continuous improvement becomes a way of doing business. A strong program is still required to drive excellence, but it cannot begin without these foundations being established first.

Making a Business Case

Although OpEx has been around in other industries for years, it has recently become a focus area for pharmaceutical and biotechnology organizations. As many drugs mature through their life-cycle process, innovation and total cost reduction become essential. Organizations must change the way they are doing business and challenge existing capabilities. Because the true capabilities of each organization lie in its operations, many excellence programs are launched in this area. OpEx is a way for organizations to drive their capabilities to world-class levels. Although it is often credited for achieving world-class status, the success of an organization is truly linked to its knowledge base. Success in evolving and OpEx comes from teaching employees how to evolve and driving their understanding of why evolution is essential.

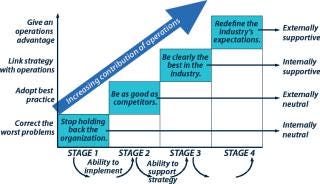

Figure 1:

BAYER HEALTHCARE (WWW.BAYER.COM/EN/HEALTHCARE.ASPX)

Hayes and Wheelwright explain that to become truly excellent in operations, an operation must redefine expectations and consider its business in a new way (1). OpEx organizations help drive a focus around this philosophy. Changes are “owned” by operations, and the people doing the work and are simply facilitated by an OpEx organization. This model is critical (Figure 1), and it forms part of the explanation and business case presented to trainees so they can look at operational excellence as more than an initiative or organization, but a way of doing business that is critical to creating a competitive advantage and sustaining growth.

Figure 1: ()

Training Development

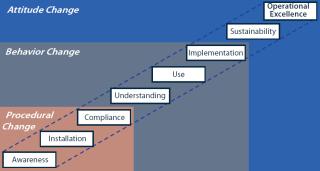

At Bayer, our objectives were to train 85% of employees at each launch site, achieve awareness of 75% based on the first phase of employee feedback after training, achieve an applicability and realization score of >50% based on the second phase of employee feedback after training, and achieve 94% sustainment of active initiatives in all production areas across the launch site. When the training was under development, several programs were reviewed and benchmarked. Although many organizations had either fundamentals training or what they called “yellow-belt” training, none of those observed included a blend of soft skills, which represent the foundation of operational excellence and technical tools training (Figure 2).

Figure 2: ()

Most training programs we looked at did not cater to all learning types (tactile, visual, and audio learners), which is critical because trainee populations tend to be split almost evenly among those three types. Through handouts, slide presentations, exercises, and simulations, trainers can hit all areas with even focus to ensure that absorption of material is achieved for the majority of trainees. In addition, very few training programs focused on removing misperceptions, which we find to be one of the largest reasons for resistance. Instead of focusing solely on providing tools training, the team at Bayer launched its program with knowledge sharing about operational excellence. In year two, after all employees had received OpEx fundamentals training, the team shifted to heavier tools training after proof-of-concept kaizen (Japanese for continuous improvement) and projects had been successfully completed.

We used two key approaches to make our training effective: We started soft, and we used NLP and Lewin’s change model to redirect thought development and drive different behavior patterns. The latter began by asking, “What is operational excellence?” and providing a new definition. Then we produced a map of our current state to show that we were not operationally excellent (thus providing a business case. Next we showed that we could become operationally excellent by detailing our future state and the benefits it could bring. With practice we would explain how we could become even better and achieve world class.

Effecting behavioral change and attitude shifts represents a major challenge for all organizations. According to Edgar H. Schein, the key of Lewin’s change model (Figure 3) is to see that human change, whether at the individual or group level, is a profound psychological dynamic process that involves painful unlearning without loss of ego identity and difficult relearning as people cognitively attempt to restructure their own thoughts, perceptions, feelings, and attitudes (2). One day of training cannot completely alter a culture, but it can help employees change their perceptions and start behaving differently when they participate and support OpEx initiatives. Once misperceptions are removed, employees are free to start building OpEx into their daily work as a practice and philosophy of continuous improvement that is owned by all.

Figure 3: ()

Many employees have built up misperceptions about operational excellence, for example feeling that it creates less job security. If launched incorrectly, OpEx can be seen as a pure cost-cutting effort focused on only quick cuts (e.g., head count). People may fear that it will point out their flaws. To break these misperceptions, an organization must first get its employees’ attention so that they will be open to listening to the true use and benefits. To that aim, our team developed a training program that starts out soft.

The first half of a day-long training session specifically focuses around the foundation of operational excellence, which is made up of soft skills required to enable good practices. This critical foundation is far less controversial than the OpEx concept itself, so employees do not immediately move into a fear or defensive mode in which they focus on personal safety rather than on learning. If trainers can help employees move up Maslow’s hierarchy of needs diagram (Figure 4) to a productive state in which they focus on self or personal growth, then they will be more receptive when training later focuses on tools and philosophies critical to operational excellence.

Figure 4: ()

After its audience is open to absorb information, the training team seeks to break misperceptions. Our team focused on the very basics of neurolinguistic programming to redirect trainees’ thought-development process in this area. NLP is a multidimensional process that involves developing behavioral competence and flexibility along with strategic thinking and an understanding of the mental and cognitive processes behind behavior (3). Techniques focus on identifying, using, and changing patterns in the thought processes that influence people’s behavior to improve the quality and effectiveness of their performance.

Here the trainers first require participants to ask the question, “What is operational excellence?” not only internally, but aloud as well. We then discuss their current understanding of operational excellence before moving to a deeper explanation. Throughout this training, the foundation of OpEx is provided as well as a thorough overview of the tools and techniques used to drive its philosophy and initiatives. This moves the focus to a personal level, showing employees that they truly are the owners of world-class operations.

The training program also walks trainees through many hands-on exercises so they can see for themselves that their organization is not yet operationally excellent. The main exercise is a simulation: making something like Play-Doh modeling compound. Employees are walked through an entire value-stream process from supplier to customer, with all the inefficiencies in most companies exaggerated to show their effects downstream and on the entire process. Mapping out the process leads to a discussion of the organization’s challenges. Here employees are asked whether they are operationally excellent or not, and inevitably they respond with the realization that they are not. It is the realization state of NLP. Here, trainees finally start seeing OpEx in a new light.

The Simulation: Bringing the Point Home

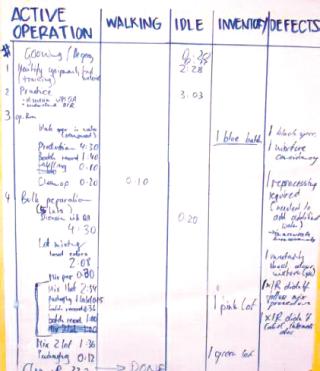

Define/Measure (Identify What’s Critical to Quality and Observe Waste): Trainees are asked to move into the role of employees at “Play-do Co.” The first runs have built-in inefficiencies that help participants see how inefficiencies at each step affect the entire chain. The key of this activity is to reach all types of learners, whether kinesthetic, audio, or visually oriented. Learning by doing has been proven to be one of the most effective knowledge distribution channels, and the simulation drives off of this best practice. It works on creating a process that shows how a “push” system can have batching inefficiencies, excess inventory, cycle-time effects, and poor customer performance. During the initial run, analysts pull data on cycle time, waste time, defects, scrap, and inventory (Figure 5). Customers report on performance to expectation, which is very poor during the first run.

Figure 5: ()

Analyze (Reviewing the Current State): With data from the first run, trainees work together to develop a current-state value stream map (Figure 6). During its development, trainers provide an overview and training on value-stream mapping. After the map is created, the group bullet-lists and discusses waste and inefficiencies in their process (Figure 7), then relates them to those seen within their organization. After the current-state map is developed, trainers start discussing major operational excellence tools and move into a technical mode. By this point, most participants have been pulled into the process and are eager to improve their struggling “Play-do” company.

Figure 6: ()

Figure 7: ()

Improve (Developing the Future State): After tools training, the trainers break the participants into four teams focusing on inventory/ resources, flow/layout, documentation/ training, and customer focus/ innovation. Figure 8 illustrates their analyses. Customers are interviewed to understand their true needs so a new process can be developed around those needs. The four teams focus on using the tools they just learned to improve their process. This not only helps drive active participation, but it also helps drive understanding and applicability. Once the teams have completed their plans, each team leader reports to the entire group (as shown in the photo on the first page of this article). Reporting as a team to your peers is a critical piece of this exercise. It helps drive ownership of the change process.

Figure 8: ()

After all four teams have presented their plans, the entire group walks through a future-state mapping exercise. Quality variations and defects are addressed by the teams through building more robust quality into their process. Inventory is addressed through development of inventory-control systems such as a raw material kanban (Japanese for a signaling system for triggering action) and supplier-managed inventory and a finished-goods production kanban to help trigger production of the right piece only when a void is created. Poka-yoke (Japanese for fail-safing), color coding, and special labeling are also developed. A new optimized layout is developed to support a continuous-flow process, and the group moves away from an isolated island layout. Communication is also improved with new visual signals and identification of roles and responsibilities.

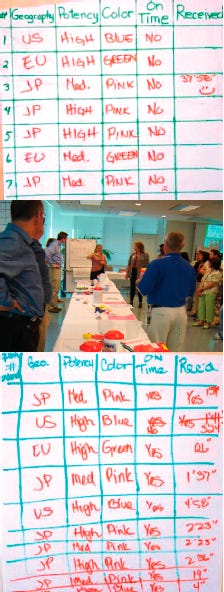

Once the future state is described, the four groups move into actively changing their organization to become a customer-focused lean and efficient plant that is resilient to customer needs and fluctuating demands. The second run after this improvement is much smoother, but trainees quickly realize with their newfound knowledge that there is more work to be done. For the remaining portion of the exercise, they are tasked to continuously improve their process until it is running as desired. By the end of the second run, customers have 100% fulfillment (Figure 9), employee satisfaction has increased, scrap rates are almost negligible, and inventories are all within desired ranges. The difference is dramatic and obvious to all involved.

Figure 9:

With the simulation complete, trainees regroup and discuss the future state and changes that they not only experienced, but also made happen. Most classes ends with cheers, and the employees usually leave with a sense of excitement.

Feedback: Our team has put two forms of feedback into place. One is the “Bs and Cs” (Benefits and Best practices, Challenges and Concerns), represented by a large white sheet of paper on which employees place sticky notes throughout the day on either side to provide immediate feedback (Figure 10). This is a mechanism trainers can use to react immediately to feedback as it is given. In addition, employees are given a follow-up survey that they take at the end of class before leaving. It provides feedback that can be used to improve the training program overall in preparation of later classes. The survey is broken into two parts: one that focuses on the training set-up and execution, and the second focusing on overall absorption of information and applicability.

Figure 10:

From the Foundation Up

According to the survey results, our team achieved its desired goals. Even more importantly, the OpEx organization saw dramatic shifts in all employee participation supporting critical projects, kaizens, and workouts. The employees developed a new understanding of what OpEx is and what it can do for them and their organization. Although execution and follow-up activities are key to maintaining the appropriate perceptions, it is critical to start out on the right foot with employees on board before change can really start moving at the company’s desired speed.

1.) Hayes, RH, and SC Wheelwright. 1984.Restoring Our Competitive Edge, John Wiley and Sons, New York.

2.) Schein, EH 2004. Kurt Lewin’s Change Theory in the Field and in the Classroom: Notes Toward a Model of Managed Learning.

3.) Dilts, R, and J DeLozier. 2000.Encyclopedia of Systemic NLP and NLP New Coding, University Press, Scotts Valley.

4.) Borisoff, D, and L Merrill. 1998.The Power of Communication: Gender Differences As Barriers, Waveland Press, Inc, Long Grove.

5.) Brassard, M 1995.The Team Memory Jogger, GOAL/QPC and Oriel Inc, Madison.

6.) Canfield, J, MV Hansen, and L Hewitt. 2000.The Power of Focus, Health Communications, Inc, Deerfield Beach.

7.) Eckmann, H Leadership for Supply Chain Managers.

8.) Hagberg, JO 1994.Real Power: Stages of Personal Power in Organizationsrevised edition, Sheffield Publishing Co, Salem.

9.) Kidder, RM 2003.How Good People Make Tough Choices, Harper Collins Publishers Inc, New York.

10.) Kotter, JP 1990.A Force for Change: How Leadership Differs from Management, Free Press, New York.

11.) Northhouse, PG 2004.Situational LeadershipLeadership Theory and Practice, Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks.

12.) Ohno, Taiichi 1988.Toyota Production System, Productivity Press, Portland.

13.) Parker, G 1998.Teamwork: Action Steps for Building Powerful Teams, Successories Library Inc, Aurora.

14.) Waitley, D, and B Matheson. 1998.Attitude: Your Internal Compass, Successories Library Inc, Aurora.

You May Also Like