Voices of Biotech

Podcast: MilliporeSigma says education vital to creating unbreakable chain for sustainability

MilliporeSigma discusses the importance of people, education, and the benefits of embracing discomfort to bolster sustainability efforts.

Biotech was “born” in the 1970s. Since that time innovation by biotech pioneers has brought more than 200 medicines and vaccines to fruition for difficult-to-treat indications including oncology, HIV/AIDs, diabetes, and immune disorders. Another 400 biotech products targeting 200 diseases are currently in clinical trials, and 700 compounds are in preclinical development (1). Overall, the industry had a banner year in 2007, with an 8% increase in biotech revenues and a total of more than $29.9 billion (US) in investment capital raised in Europe and the Americas. Record levels of financing and deal making suggest strong confidence in this sector, with mergers, acquisitions, and alliances in the amounts of US$60 billion in the United States and $34 billion in Europe (2).

Biotech is poised to capitalize on the current challenges confronting Big Pharma: looming patent expirations on blockbuster medicines and a dearth of new compounds in the pipeline to replace them. Current pharmaceutical business models are in the doldrums and operationally incapable of rapid action. Cost cuts are prompting consolidation and restructuring to improve productivity and innovation, but these approaches buy only so much time until successful new models emerge. In the interim, Big Pharma is turning to structured biotech business alliances to supply assets and products that will address true unmet medical needs and keep them financially viable and competitive.

The need to fill pipelines quickly is compounded by slow regulatory approvals, the volatile nature of financing, concerns about costs for prescription pharmaceuticals, late-stage product failures, and increased complexity in trial design and development costs. Despite 8-10% increases in R&D spending, a record low number of NDAs (new drug applications) were approved in 2007 as the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) faced significant resource constraints and increased scrutiny from Congress on safety issues (3).

The climate for small and emerging companies is not better in Europe. Pricing pressures in the United Kingdom are forcing developers to negotiate reduced prices for the National Health Service (NHS). In one company’s agreement to gain market access, the developer even guaranteed a refund to payers if patients fail on their treatment (2). In England and Wales, the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE), a special health authority of the NHS, holds increasing influence with cost-benefit justification in product access. NICE conducts clinical appraisals of new treatments and makes decisions that are starting to influence American health insurance pharmacy benefit plans.

The Role of Outsourcing in Early Drug Development

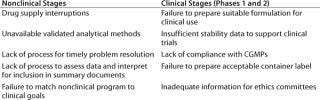

The urgency to fill pipelines and prevent delays creates a greater need for biotech to make preclinical development as efficient as possible (Table 1). Effective screening strategies are moving a higher proportion of new chemical entities (NCEs) into preclinical and early clinical development. International regulatory initiatives now provide a fairly standardized approach for small molecule preclinical safety testing, although the biologic guidelines are less defined and subject to interpretation.

Table 1: Common causes of delays in product development

Preclinical safety studies are performed in compliance with good laboratory practices (GLPs), a set of regulations that ensure conformity to analytical, data, quality, and safety standards. Significant infrastructure is required for GLP compliance. Establishing and maintaining this infrastructure is often cost and time prohibitive for small and emerging biotech organizations.

Biologics represent nearly 50% of all drugs currently in development, and the global market share of prescription drugs that are biologics is about 13% (2,3,4,5). However, biotech organizations are not engaged in this increased development activity alone. These organizations embrace outsourcing as a business practice, and in 2007 they generated roughly 30% of global contract research organization (CRO) revenue, up from 21% in 2004 (3).

Outsourcing can be strategic or tactical, serving as a means to balance the workload for sponsors and expand capacity, manage costs, draw on external expertise, and allow biotech organizations to focus internal resources on high-value activities. Since 2001, growth in biotech R&D outsourcing expenditures has outpaced the overall global R&D spending growth rate: 15% versus 11% (6).

Synergies of CROs and Biotech

Large, global CROs are uniquely positioned to help biotech organizations achieve strategic goals and hit target milestones on product development regardless of company maturity. The depth and breadth of expertise in a global CRO is accumulated from hundreds or thousands of studies, compounds, and customers. Its insights into study designs, regulatory paths, timelines, and capacity are invaluable. The institutional expertise and experience available in global CROs can help small emerging biotechnology companies advance development compounds through development. After determining the preclinical tests required for biologic safety and efficacy studies, CROs often can schedule appropriate resources so the biotech company avoids incurring expensive internal infrastructure or facility costs.

Strategies for testing biologics vary widely from one molecule to the next. Unlike small molecules for which animal models for testing safety and efficacy are readily available, biologics by their very nature are often designed to target receptors, mechanisms, or diseases that exist only in healthy or diseased humans. Biologics often do not generally exhibit “classic toxicity” observed with small molecules. In a “standard” toxicity test, doses are increased to a point where toxicity is observed or until giving higher doses is no longer feasible. Biologics often cause no toxic effects, or they cause adverse effects only because of exaggerated pharmacology, so safety testing must necessarily deviate from traditional studies and animal models. Despite efforts to standardize and update regulatory guidelines for testing biologics, many “gray areas” remain. CROs, with their plethora of trials and experiences, can often devise the best regulatory strategy and course of action.

Specificity of biologics for human targets often precludes safety testing in laboratory animals. In some cases, biologics can crossreact with target receptors in laboratory animals; in such instances, toxicology evaluations in sensitive species may be predictive of adverse effects in humans. In the absence of cross-species activity, an alternative approach involves using a homologous molecule directed against an animal target (extrapolating, for example, the findings from a monoclonal antibody directed against a rat target to a development candidate with a human target). Transgenic models are also occasionally established for biologic testing by genetically transferring a human molecular target into an animal model. A limited number of facilities around the world offer such tests. A large CRO may have its own primate and transgenic testing facilities. If it doesn’t, it will have established relationships and contacts to help companies find the necessary resources from niche providers.

The range of biologic testing services varies with the type of molecules in development and the size of the company. Preclinical services for biologics typically include

Biosafety and cell banking

Batch-release assays (analytical characterization and cell-based potency assays)

Preclinical safety testing (primate, transgenic, or xenograft models)

Bioanalysis (immunoanalytical methods)

Anti-drug antibody assay development and testing

Immunotoxicity screening (including cytokine screens)

Immunohistochemistry (tissue cross reactivity and tissue microarray assays).

From IP to Acquisition

Big Pharma is counting on biotech’s innovation to help it survive in today’s economy. Many small and emerging companies are founded by passionate innovators who challenge conventional wisdom and create novel therapeutics. Intellectual property (IP) represents all the equity of such companies. They will shop their IP to venture capitalists or other potential customers to raise capital for continued operations. Buyers require a certain amount of data to conduct due diligence and effectively evaluate a product. Often their request is for human data, so the biotech company is obligated to carry through its products to proof-of-concept clinical trials.

Big-Pharma investors are steering biotechnology companies to large, reputable CROs for preclinical development assistance. The average cash outlay for R&D in preclinical development for an approved biologic was $198 million in 2006, 46% higher than for traditional pharmaceuticals (7). With that kind of investment, many buyers want a good idea of how the molecule behaves in humans. Many times the buyers are pharmaceutical customers that have used preclinical CROs. Such buyers are accustomed to certain standards, quality, and report formats, and by steering the biotech to their reputable CROs, due diligence evaluations become more credible. Even though the costs may be higher, preclinical development packages are perceived to have added value when prepared by a reputable, global CRO.

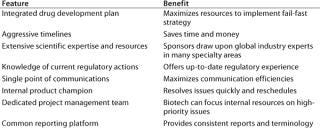

Program Management

Small biotech companies characterized by limited numbers of employees and capital. They are already stretched thin managing multiple priorities and rarely have the time or resources to monitor multiple different niche contract providers. Biotech resources tend to be more R&D focused, and that’s where hiring a large, multiservice CRO for development work is ideal.

Table 2: Features and benefits of program management

Integration and coordination of the various tasks and stages of development are essential to reducing development times, improving efficiency, and enhancing overall quality of a drug development dossier. The management of biotech programs is not all that different from the management of small-molecule programs. Biotechs benefit from working with program management teams offered by full-service CROs because they have the resources, experience, and expertise garnered through years of conducting a wide variety of development programs.

Initially, a needs assessment is conducted by the CRO project team to understand the goals of the program and how far a biotech company is willing to take its compound. Biotechnology companies generally require more discussion of program design, largely because regulatory guidelines for biologic molecules are not always as clear as those for small molecules. If the biotech wants to develop its molecule through certain milestones (such as human data from phase 1 or 2a), the CRO develops an integrated product development plan by designing and executing studies that generate data for unanswered questions and anticipates questions that will inevitably arise over the course of evaluation. A single project manager may be assigned to manage the lifecycle of the program from the earliest function of cell banking to phase 2a when it is handed off to a clinical development team.

Critical Parameters of the Plan

Each succeeding milestone along the early development paradigm achieved by biotech organizations represents potential revenue or equity. Generally speaking, the farther development progresses, the higher the price a biotechnology company can ask for its compound.

To hit those all important milestones, an effective project plan anticipates resources, interdependencies, and timelines needed for successful implementation of the development plan. Budgets are established, a project team assembled (including a representative responsible for manufacture of the product), and supplies of the bulk drug or reference standards are obtained before project initiation. Other critical resources include key staff, the appropriate animals, and development space.

A key milestone is the first regulatory submission, a clinical trials application (CTA) or an investigational new drug application (IND). As part of the early planning process, the critical components and interdependencies for the regulatory submission are identified. The CTA or IND submission represents the first opportunity to receive regulatory endorsement for the NCE/NBE (new biological entity) and is an important early validation of the product development strategy. Not surprising, a successful CTA or IND is a key milestone investors request from biotechnology companies before considering purchase of their compounds. In addition to the preclinical laboratory services already mentioned, preparation of a CTA/IND package also requires the following components:

Regulatory forms

Chemistry, manufacturing, and controls (CMC) documentation

Summaries, overviews, and individual study reports

Investigator’s brochure

Clinical protocol for the first in human study.

All those documents require assembly into a common technical document (CTD) according to a format prescribed by ICH, and it is submitted electronically or on paper.

Communication: Open and effective communications are critical to successful drug development. Biotechs often work with CROs in the same region or time zone to track and respond to progress of their projects. For small biotechs, preclinical development is a huge undertaking, both risky and expensive. If a package does not succeed, failure may expose the company to bankruptcy or sale. At this stage, drug development is often unpredictable. Challenges with resource availability or unexpected findings can cause project delays. Frequent and effective communications permit a team to monitor progress, ensure that intermediate tasks are addressed, resolve problems, and keep timelines and budgets within expectations. Funneling communications through a program manager provides a single point of contact responsible for disseminating the information to the project team.

Globalization and the Preclinical Environment: The globalization that has consumed clinical development is not as prevalent in the preclinical marketplace. Most preclinical CROs that specialize in biologics testing are located in Europe or the United States. The Asian preclinical CRO industry is in its infancy, and differences in language, time zones, and regulatory practices add to the complexity of outsourcing in Asia. On top of those challenges, shipping and customs regulations make it notoriously difficult to transport primate samples across borders. These barriers are likely to confine testing to locations where primate facilities exist.

Scientific and Regulatory Oversight: Another benefit of working with full-service CROs is the scientific and regulatory oversight of seasoned professionals. Their experience and foresight may address any of a number of challenging issues that threaten to derail progress. Issues including insufficient quantity of the biologic, difficulties with formulation, unanticipated species differences, or unexpected adverse effects can cause substantial delays, repeat work, or even the demise of the project. More than likely, the CRO staff has experienced similar issues in the past and can lend their expertise to overcome seemingly insurmountable hurdles.

Handoffs from Preclinical to Clinical Development: Program managers with large CROs understand the planning and coordination required for handoffs from preclinical to clinical programs. A preclinical IND/CTA program generally requires six to eight months for completion; therefore, early planning for safety and efficacy human trials needs to happen concurrent with the preclinical program. Early safety studies should be actively monitored by clinical representatives to assess issues such as compound supply or quality, formulation issues, and adverse effects. These can have significant impact on the design and timing of clinical trials. Proactive resolutions of issues that arise during preclinical programs facilitate smooth transition of compounds from the preclinical to clinical phase. An experienced program management team serves as a linch pin to coordinate tasks and communication between preclinical and clinical representatives.

Opportunities Abound

Biotechnology companies are poised to fill Big Pharma’s dwindling pipelines, and the opportunities have never been better for small, emerging companies. However, preclinical development must be conducted as efficiently as possible to capitalize on the urgency of these prospects. Large, global CROs offer facilities and resources for preclinical programs, as well as the insight and scientific expertise of program management teams gathered over the years with clients large and small.

When time and quality is of the essence, effective program management can help ensure a streamlined and comprehensive pathway that speeds preclinical development. It is not always clear how a biologic molecule is going to behave in animals or humans, but with clearly defined goals and endpoints, backed by a solid program management team, development risk is mitigated for faster go/no-go decisions.

1.) The Biotechnology Industry Organization (BIO) Biotechnology Industry Facts.

2.) Ernst & Young 2008. Beyond Borders: Global Biotechnology Report.

3.) MacDonald, G. 2008.Biotechs Generate 30% Annual CRO Revenue Outsourcing pharm.com.

4.) Reymond, E. 2007.Biotech CEOs Expect Increase in Outsourcing.

5.) Business WireIMS Health Reports Global Biotech Sales Grew 12.5% in 2007, Exceeding $75 Billion.

6.) Flanagan, N. 2008. Small Biotechnology Firms Reach Out to CROs for Help. GEN www.genengnews.com/articles/chitem.aspx?aid=2383&chid=4 (accessed 6 October 2008). 28.

7.) Tufts Center for the Study of Drug Development 2006. Cost to Develop New Biotech Products Is Estimated to Average $1.2 Billion. Impact Report. 8.

You May Also Like