Voices of Biotech

Podcast: MilliporeSigma says education vital to creating unbreakable chain for sustainability

MilliporeSigma discusses the importance of people, education, and the benefits of embracing discomfort to bolster sustainability efforts.

Human medicinal product manufacturers face complexity and uncertainties regarding operational performance. Effective training management plays a major role in support and implementation of a pharmaceutical quality system. The minimum regulatory requirement is to employ adequately trained personnel with sufficient knowledge, skills, and experience. Software-based e-learning training methods are used widely across pharmaceutical companies. Achieving quality compliance depends significantly on several factors, from training preparation to assessments.

To comply with the current regulatory requirements, pharmaceutical companies need to implement learning management systems for training their employees — either e-learning or classroom (paper) based — as part of their overall quality systems. All such processes carry some residual risks and challenges during implementation. Based on regulatory agency inspection findings and industry expert perspectives, inherent risks in training processes include those related to training evaluation and retraining controls. Retraining is necessary, for example, when an employee fails to qualify or does not meet evaluation criteria, or when training evaluations are delayed or ineffective. Therefore, we consider it to be worth studying possible risk factors related to retraining processes and controls to help the industry work toward understand and mitigating those risks.

Risk Factors (3) Control of the retraining process (4) Effectiveness of the training (5) Identification of metrics for training effectiveness (6) Completion of training for all relevant personnel before the planned effective date for a given standard operating procedure (SOP) (7) Training evaluation controls (8) Changes in job roles (9) Multiple testing attempts (particularly with e-learning platforms) (10) Controls to prevent employees from resuming job functions before they are qualified to do so |

The general process flow of training programs in the pharmaceutical industry includes

• identification of training needs

• creation of a written procedure

• development of a training plan

• execution of training according to that plan

• evaluation of the training/retraining process

• documentation and archival of records.

At many companies, investigations related to quality events conclude with the proposed corrective action and preventive action (CAPA) of “retraining.” It usually is performed as part of immediate/corrective actions for the reported quality events. Unfortunately, many companies consider the “retraining” to be the only CAPA for such events.

Regulatory requirements for training processes and documentation are not specifically prescriptive, so pharmaceutical manufacturers follow different types of approaches. Few studies have been conducted about retraining evaluation controls. Our aim is to provide quality insight toward training evaluation processes specific to relevant procedures and their controls.

First, we summarize current regulatory approaches related to training requirements. Then, based on a survey of available literature, we present our understanding of retraining procedures and controls followed across the pharmaceutical industry. Next, we identify and analyze risk factors and procedural controls that companies use and measures that they can take to mitigate those risks. We present an empirical study of the identified risks related to retraining procedures. Our results are derived from the responses during semistructured interviews, a structured questionnaire (through email), and online group discussion with quality-unit professionals. Finally, we conclude with a discussion of the identified risk factors, existing controls, and mitigation actions.

Regulatory Sources

Most current regulatory guidelines describe minimum requirements for training as part of compliance for product quality of human medicinal products. Below are sources of regulatory requirements specific to personnel training.

United States: The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) requires every manufacturer of drugs or medical devices to train every employee beginning with regulated procedures based on requirements laid out in the US Code of Federal Regulations (CFR). Good manufacturing practice (GMP) training requirements are defined in 21 CFR Part 211.25 (1). FDA guidance is specific:

Each person engaged in the manufacture, processing, packing, or holding of a drug product shall have education, training, and experience, or any combination thereof, to enable that person to perform the assigned functions. Training shall be in the particular operations that the employee performs and in current good manufacturing practice (including the current good manufacturing practice regulations in this chapter and written procedures required by these regulations) as they relate to the employee’s functions. Training in current good manufacturing practice shall be conducted by qualified individuals on a continuing basis and with sufficient frequency to assure that employees remain familiar with CGMP requirements applicable to them. (2)

Training-related predicate rules that are covered by 21 CFR Part 11 on electronic records can be found in 21 CFR Part 111.14(b)(1), which stipulates that they include “documentation of training, including the date of the training, the type of training, and the person(s) trained” (3, 4). Section C highlights an operator-monitoring program in which adverse trends will trigger investigations. Follow-up actions can include increased sampling, increased observation, retraining, gowning requalification, and in some instances, reassignment of individual employees to operations that lie outside aseptic manufacturing.

Europe: Annex 1, section 2, of the European Union’s GMP regulations specifies that personnel should have adequate qualification and experience, training, and aptitude, with a specific focus on the principles involved in the protection of sterile products during manufacturing, packaging, and distribution (5). Section 7.6 requires systems for disqualification of personnel from entry into cleanrooms based on ongoing assessments and/or identification of adverse trends from a personnel monitoring program — and/or after employee participation in a failed aseptic process simulation study (6). Once an operator has been disqualified, then retraining and requalification should be completed before permitting that person to have any further involvement in aseptic practices. Section 7.18 specifies further that air-flow visualization studies should be considered as part of operator training.

Those requirements clearly indicate the intensity and importance of operator training programs and retraining in Europe. EU guidelines specify that all necessary facilities for GMP include appropriately qualified and trained personnel (7). Schedule M specifies that drug manufacturers ensure, in accordance with written instructions, that all personnel in production areas or quality control laboratories receive training appropriate to their duties and responsibilities (8). And they must be provided with regular in-service training.

Part 2 of the basic requirements for active substances used as starting materials (Volume 4) in the EU GMP guidelines for human and veterinary medicinal products also mentions personnel qualification requirements, including training and records (9).

International: Chapter 2 in Part 1 of the Pharmaceutical Inspection Convention and Cooperative Scheme’s guide to current good manufacturing practices (CGMPs) for medicinal products addresses the requirement that initial and continuing training of department personnel will be carried out and adapted according to need (10). It specifies that visitors and untrained personnel preferably should not be taken into production and quality-control areas. If that is unavoidable, then those people should be supervised closely and informed in advance about personal hygiene and prescribed protective clothing.

The Health Canada regulatory agency specifies training requirements in a GMP guide for drug products (11). It describes all key elements for GMP compliance, including qualified and trained staff. Annex 2 of the World Health Organization’s (WHO’s) GMPs for pharmaceutical products includes key principles related to training, including that visitors and untrained personnel should not be taken into production and quality-control areas (12).

The International Council for Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Pharmaceuticals for Human Use (ICH) discusses personnel qualification requirements, including training and records, in its Q7 GMP guidelines for active pharmaceutical ingredients (13).

Research Review

It is important to understand that the implementation of training programs carries risks, and this is particularly true for retraining procedures and controls. Retraining procedures and controls carry residual risks, in particular. Thus, understanding, assessing, identifying, analyzing, and mitigating those risks in retraining requires a thorough level of understanding about what training evaluation and control entail. ICH Q9, published in Europe as EMA/CHMP/ICH/24235/2006, provides a reference for industry professionals to follow (14, 15). Section II.1 states that quality risk management (QRM) should be part of integrated quality management, which includes training and education.

Issues arise in conventional quality management and root-cause analysis of training and retraining. The policies and directives of senior management often greatly influence training performance at drug companies by controlling the availability of training personnel and resources, timing constraints, and other considerations that significantly affect training efforts (16). Training and qualification for aseptic processing pertain to gowning effectiveness, aseptic technique, materials handling, and specific process-related training on equipment and cleanroom behavior (17). Specific training is needed to manage and handle cleanroom environments, including monitoring of the processing environment, gowning of personnel, transfer of materials within the aseptic processing area, and performance of aseptic techniques that include setup, filling, and environmental sampling (18). CAPAs and root-cause analyses are key to training and documentation at all pharmaceutical companies (19). Employees and trainers should focus on specific topics and approach training as an ongoing and dynamic process. Continuous training programs are mandated for adequate quality compliance.

Also important is GXP training for new-employee orientation. Such training programs should cover regulatory requirements, behavioral aspects, qualification of trainers (“train the trainer” programs), root-cause analysis, and regulatory updates with warning-letter information (20). Employees should follow comprehensive training plans that include participating in continuous CGMP training modules. Necessary considerations for effective training include policies, standards, and strategies managed by qualified instructors who can facilitate proper training (21). By assessing trainee proficiency, companies can gain clarity about the educational and experience requirements people need for qualification (22).

Many pharmaceutical companies have failed to identify the importance and necessity of quality-training programs, which can lead to a workforce that has failed to develop crucial job skills. Some employers have failed to assess the aptitude of their operators before assigning specific training responsibilities to them. Each company needs a system of providing continuous training that brings safe and effective products as well as increased profits (23). Maintaining adequate quality systems is mandatory (24). Managers should discuss human errors and retraining status with respect to global regulations pertaining to complaint investigations in pharmaceutical manufacturing (25). Training is a planned and systematic attempt to improve the aptitude, attitude, skills, and knowledge of a person to perform specific tasks effectively and efficiently. And overall talent management requires identifying, attracting, developing, compensating, and especially retaining the best possible employees (26).

Training is a dynamic process for ensuring that personnel will be capable of performing their assigned functions. CGMP regulations contain only general expectations, and the FDA has issued no guidelines on complete training. Although training programs are generally in place, their quality and effectiveness could be inadequate at some pharmaceutical companies (27). An appropriate system will provide information about the training plan and associated roles and responsibilities for designing, developing, implementing, evaluating, and recording training activities (28). Managers should design training processes to include competency-based training; in many cases, no competency-based training or qualified trainers are present (29).

Aseptic-process training should be specific and cover both operational and practical aspects related to cleanroom environments and practices, operator clothing and activities, and critical-zone interventions, including assembly of equipment before operations begin (30).

In our literature review, we discovered other considerations that can contribute to identifying risk factors in training but are not clearly specific to procedures and controls in retraining. These include retraining evaluations, timelines for retraining, removal of employees from work scheduling, and delays in retraining evaluations.

Analysis of Retraining Risk Factors

Over 10 years ago, Malcolm Ross addressed training and retraining issues related to CAPA processes in conventional quality management and root-cause analysis (16). He specified that policies and directives of upper management often greatly influence the performance of training programs. Two decades ago, James Akers et al. highlighted key risk areas in aseptic-process training and qualification related to gowning effectiveness, aseptic techniques, specific process-related activities and equipment, and evaluation of cleanroom aptitude (17).

We believe that many other, hidden risk factors related to retraining evaluation can affect training processes and ultimately a company’s overall quality management system. We tested that hypothesis with semistructured interviews and a structured questionnaire, as well as group discussions with relevant quality-unit professionals at major pharmaceutical companies in Hyderabad and Bangaluru (states of India).

Research Methodology: Our purpose was to detect possible risks involved in evaluation of retraining. Based on our review of available research articles, regulatory guidelines on training requirements, and our own work experience in retraining processes, we identified 10 key risk areas (listed in the “Risk Factors” box) and used them to draft our survey questionnaire. To validate those identified risk factors and finalize the questionnaire design, we conducted a pilot study with a panel of relevant subject-matter experts (SMEs) from different pharmaceutical companies. The four experts each had a minimum of 20 years of experience in a quality function within the pharmaceutical industry, and they discussed with us the identified risk elements and overall training processes, evaluations, controls, and regulatory requirements. In the end, we made a few changes to the initially identified risk factors, but the core principles did not change. Then, we finalized the questionnaire for validation through our survey process.

To validate the importance of our identified risk factors, we conducted semistructured interviews with quality-unit professionals involved in the manufacture of human medicinal products in India. Participants were selected based on their job roles (responsibility for quality-unit function), with each participant having 10 years of such experience at minimum. After sending email inquiries inviting 17 pharmaceutical-quality experts to participate in the survey, we received 11 confirmations and conducted 10 interviews/discussions through both questionnaires and online group discussions between January and March of 2022.

The survey questionnaire was designed to identify existing controls in employee-retraining evaluation procedures and controls, with a focus on the retraining of unqualified employees. Most such activities are classroom (paper based) and e-learning (software based) training. Our survey questionnaire was designed to get information about procedural controls pertaining to such retraining procedures:

• If an employee fails to meet evaluation acceptance criteria, how does retraining follow?

• What are the existing controls for retraining procedures?

• What risks are involved during retraining?

• What measures are used to mitigate those risks?

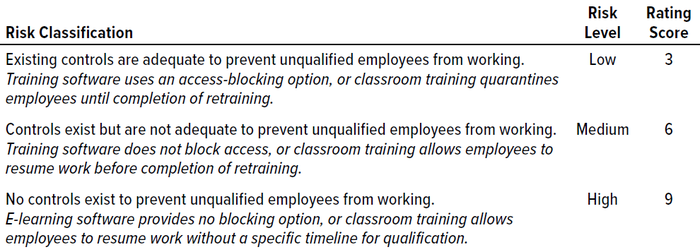

We asked discussion participants to rate risks and existing controls for each proposed risk factor using “high,” “medium,” and “low” ratings. We also asked participants to add other risk factors that they felt were relevant to the study. To derive a final score for each risk factor, we assigned values based on a three-point Likert scale (Table 1). For each risk factor, a total score is derived from the scores of the individual ratings such that a maximum total score of 90 and a minimum of 30 could be reached.

Table 1: Risk classification, level, and score for employee retraining (classroom and e-learning).

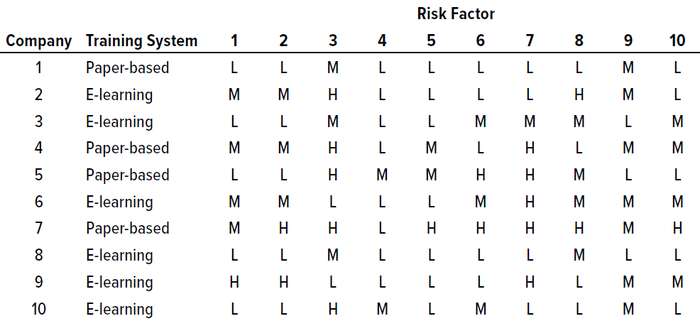

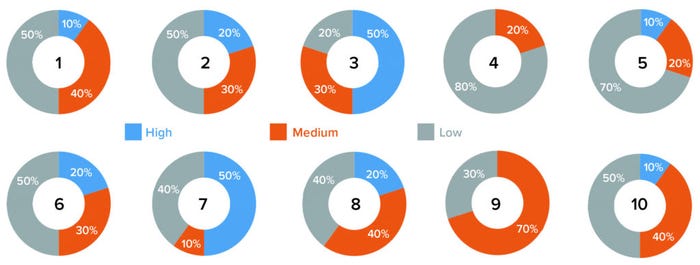

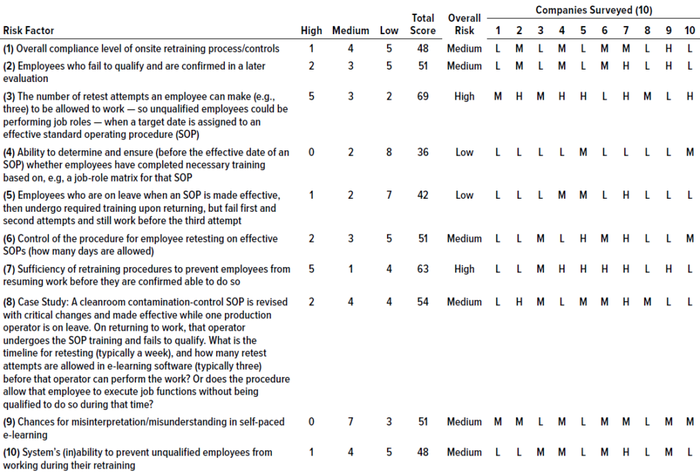

Results of Survey and Interviews: Discussions revealed that handling the identified risk factors appropriately could help reduce and mitigate those risks. Risk counts from the survey questionnaire were considered for reporting the final total risk score, but the significance of each factor was tabulated based on its risk score (Table 2). Figure 1 graphically represents our survey results. And Table 3 provides a detailed analysis of identified risk factors related to retraining evaluations.

Table 2: Survey results for identified risk factors in current retraining procedures and controls at 10 pharmaceutical companies in India; see full listings of risk factors in the Risk Factors box and Table 3.

Figure 1: Survey results graphs for 10 risk factors (see Table 3).

Based on those results, most of the analyzed risk factors are relevant to retraining evaluations from a quality-system perspective. Six of the 10 companies surveyed use e-learning software, and four use paper-based classroom training. Our results show two risk factors identified as high-risk by five out of 10 companies (50%): numbers 3 and 7, which are related to a lack of procedural controls (“Procedure allows personnel to perform job roles even at unqualified stage,” and “There are no controls to prevent personnel from working while in retraining”). At least five out of 10 respondents identified risk factors 1, 2, 6, 8, 9, and 10 as carrying medium or high risk. Factors relating to training effectiveness (4) and ability to develop metrics of effectiveness (5) were assessed as low-risk.

Table 3: Analysis of risk factors related to retraining processes from a quality-unit perspective; a score of 30–42 is low risk, 45–60 is medium, and 63–90 is high.

Our results indicate that existing retraining evaluation procedures and controls might well be inadequately defined to handle and mitigate the associated risks. We believe that the residual risk of “medium” categories will lead to high risk in the future if they persist in quality systems. Most important is that neither the e-learning software nor the paper-based (classroom) training procedures have controls to quarantine and/or prevent employees from working during retraining.

It is interesting to find that six of our proposed risk factors fell under the medium risk category in all surveyed companies. Our interpretation is that risks related to retraining evaluation procedures are evident and persist across existing training processes. In our experience, inadequate procedural and process controls lead to high risks, which in turn can cause untoward quality-system events. Interviewees with adequate experience (e.g., managerial level with at least 10 years of experience in quality-unit activities) support that interpretation.

Discussion

We have tried to identify and study possible risk factors related to retraining evaluation and controls in the pharmaceutical industry (specifically the area of aseptic processing). The identified risk factors are more relevant and comprehensive than other explanations found in literature related to training. These 10 risk factors were deemed important by experts in relevant quality units who are responsible for identifying, analyzing, and mitigating training risks in day-to-day practice at their respective pharmaceutical companies. We found that all 10 factors do have an impact on and relevance to the quality systems.

These results suggest that all the proposed risk factors are important, with high-risk factors related to inadequate procedure controls being the most critical. Results indicate that existing processes and procedural controls should be reconsidered for better mitigation of existing residual risk in retraining. The results have implications both for companies involved in the manufacture and supply of human medicinal products and for academics pursuing research in this field.

We identified and evaluated possible risk factors associated with retraining evaluation processes at pharmaceutical companies in India. We discovered procedural gaps in the adequacy of training procedures to prevent employees from working while in retraining. We also learned that e-learning software and classroom training procedures lack controls in retraining evaluation. To close that gap, quality units should meet regularly and analyze the risks present in their retraining evaluation procedures. Companies need to review the controls on their existing retraining procedures to prevent unqualified employees from working (e.g., by implementing an access-blocking mechanism in e-learning software or “quarantining” such employees until their retraining is complete). Our findings indicate that existing training procedures and controls are not managed adequately to mitigate retraining evaluation risks at the surveyed pharmaceutical companies.

These findings are similar to those of the 2009 study by Ross, which focused on retraining as part of corrective actions but did not consider risk factors related to retraining evaluation (16). That suggests that our hypothesis was even more relevant to evaluation-related risks faced by pharmaceutical companies and the conditions under which such risks can be mitigated. Our research should provide a road map to consider in future research projects in this area.

With only 10 participating companies, our sample size is limited considering the hundreds of pharmaceutical companies located in south India. So our results provide only a first foray into retraining-evaluation risk factors from a quality-unit perspective. We believe that senior management and quality-unit personnel should evaluate their companies’ retraining processes and controls through a thorough risk assessment. Adequate processes and procedural control measures should be articulated and put in place to mitigate the identified retraining risks. For future research, we recommend another survey with a larger sample size of pharmaceutical companies. It would be interesting to consider all the possible risk factors in the other sections of biopharmaceutical companies in different regions and countries around the world.

References

1 21 CFR 211.25: Personnel Qualifications. US Code of Federal Regulations. US Food and Drug Administration: Rockville, MD, 2023; https://www.ecfr.gov/current/title-21/chapter-I/subchapter-C/part-211/subpart-B/section-211.25.

2 Section V, Personnel Training, Qualification, and Monitoring. Guidance for Industry: Sterile Drug Products Produced By Aseptic Processing. US Food and Drug Administration: Rockville MD, October 2004; https://www.fda.gov/media/71026/download.

3 21 CFR 11: Electronic Records, Electronic Signatures. US Code of Federal Regulations. US Food and Drug Administration: Rockville, MD, 2023; https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cdrh/cfdocs/cfcfr/CFRSearch.cfm?CFRPart=11.

4 21 CFR 111 Subpart B: Personnel. Section 111.14. US Code of Federal Regulations. US Food and Drug Administration: Rockville, MD, 2023; https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cdrh/cfdocs/cfcfr/CFRSearch.cfm?fr=111.14.

5 Chapter 2: Personnel. EudraLex Volume 4 — Good Manufacturing Practice for Medicinal Products for Human and Veterinary Use. European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 16 February 2014; https://health.ec.europa.eu/system/files/2016-11/2014-03_chapter_2_0.pdf.

6 Section 7 — Personnel. Annex 1: Manufacture of Sterile Medicinal Products. EudraLex Volume 4: Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP) Guidelines. European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 22 August 2022; https://health.ec.europa.eu/system/files/2022-08/20220825_gmp-an1_en_0.pdf.

7 Section 1.8 (iii). Chapter 1: Pharmaceutical Quality System. EudraLex Volume 4 — Good Manufacturing Practice for Medicinal Products for Human and Veterinary Use. European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 31 January 2013; https://health.ec.europa.eu/document/download/e458c423-f564-4171-b344-030a461c567f_en?filename=vol4-chap1_2013-01_en.pdf.

8 Schedule M, Section 6.0: Personnel. Good Manufacturing Practices and Requirements of Premises, Plant and Equipment for Pharmaceutical Products. Indian Ministry of Health and Family Welfare: New Delhi, India, December 2001; https://rajswasthya.nic.in/Drug%20Website%2021.01.11/Revised%20Schedule%20%20M%204.pdf.

9 Part 2: Quality Management. Basic Requirements for Active Substances Used as Starting Materials — EU GMP for APIs. European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 13 August 2014; https://www.gmp-compliance.org/files/guidemgr/2014-08_gmp_part1.pdf.

10 PE 009-16: Part I, Chapter 2. Guide to Current Good Manufacturing Practices for Medicinal Products. Pharmaceutical Inspection Convention and Cooperative Scheme: Geneva, Switzerland, 1 February 2022; https://picscheme.org/docview/4588.

11 C.02.006 Personnel. GUI-0001: Good Manufacturing Practices Guide for Drug Products. Health Canada: Ottawa, Ontario, Canada, July 2020; https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/drugs-health-products/compliance-enforcement/good-manufacturing-practices/guidance-documents/gmp-guidelines-0001/document.html#a3.6.

12 Main Principles. TRS 986 — Annex 2: WHO Good Manufacturing Practices for Pharmaceutical Products: Main Principles. World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014: https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/trs986-annex2.

13 Section 3: Personnel. ICH Q7: Good Manufacturing Practice Guide for Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients. US Fed. Reg. 66(186) 2001: 49028–49029; https://database.ich.org/sites/default/files/Q7%20Guideline.pdf.

14 Note for Guidance on Guidance on Good Manufacturing Practice for Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients (CPMP/ICH/4106/00). European Medicines Agency: London, UK, November 2000; https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/scientific-guideline/ich-q-7-good-manufacturing-practice-active-pharmaceutical-ingredients-step-5_en.pdf.

15 Section II.1 — Quality Risk Management As Part of Integrated Quality Management, Training and Education. ICH Q9: Quality Risk Management. US Fed. Reg. 71(106) 2006: 32105–32106; https://database.ich.org/sites/default/files/Q9%20Guideline.pdf.

16 Ross M. Training, Re-Training and CAPA: A Root Cause Analysis View. J. GXP Compliance 13(1) 2009: 90–96.

17 Akers JE, Agalloco JP. Recent Inspectional Trends: Are Regulatory Requirements for Sterile Products Becoming Scientifically Undoable or Unpractical? PDA J. Pharm. Sci. Technol. 56(4) 2002: 179–182; https://journal.pda.org/content/56/4/179.short.

18 Akers J, Agallaco J. Environmental Monitoring: Myths and Misapplications. PDA J. Pharm. Sci. Technol. 55(3) 2001: 176–184.

19 Welty G. Final Implementation of the Training Module. J. GxP Compliance 13(2) 2009: 67–78; http://www.wright.edu/~gordon.welty/J_GXP_C_Final_04_09.pdf.

20 Welty G. Developing a Continuing CGMP Training Program: Part 2. J. GXP Compliance 13(4) 2009: 86–96; http://www.wright.edu/~gordon.welty/J_GXP_C_Continuing_10_09.pdf.

21 Pluta PL, Fugate F. Effective GMP: Effective Training. J. GXP Compliance 13(3) 2009: 32–35.

22 Welty G. Final Implementation of the Training Module. J. GXP Compliance 13(2) 2009: 67–78; http://www.wright.edu/~gordon.welty/J_GXP_C_Final_04_09.pdf.

23 Pai DR, et al. Personnel Training for Pharmaceutical Industry. Int. J. Pharm. Qual. Assur. 7(3) 2016: 55–61; https://impactfactor.org/PDF/IJPQA/7/IJPQA,Vol7,Issue3,Article5.pdf.

24 Section 2: Personnel Development. Guidance for Industry: Quality Systems Approach to Pharmaceutical CGMP Regulations. US Food and Drug Administration: Rockville, MD, September, 2006: 13; https://www.fda.gov/media/71023/download.

25 Haigney S. Developing a Continuing CGMP Training Program. J. GXP Compliance 13(4) 2009: 47–60.

26 India: Preparation for the World of Work. Pilz M, Ed. Springer Nature: Berlin, Germany, 2016.

27 Levchuk JW. Training for GMPs. PDA J. Pharm. Sci. Technol. 45(6) 1991: 270–275; https://journal.pda.org/content/45/6/270.

28 Gallup D, Beauchemin K, Gillis M. A Comprehensive Approach to Compliance Training in a Pharmaceutical Manufacturing Facility. PDA J. Pharm. Sci. Technol. 53(4) 1999: 163–167; https://journal.pda.org/content/53/4/163.

29 Gallup D, Beauchemin K, Gillis M. Competency-based Training Program Design. PDA J. Pharm. Sci. Technol. 53(5) 1999: 240–246; https://journal.pda.org/content/53/5/240.

30 Delattin R. E U Status of GMP for Sterile Products. PDA J. Pharm. Sci. Technol. 52(3) 1998: 82–88; https://journal.pda.org/content/52/3/82.

Venkatesan Jaiganesh ([email protected]) and Maria Ioakeim ([email protected]) are in the department of quality compliance at Medochemie Ltd., 1-10 Constantinoupoleos Street, 3011 Limassol, Cyprus; 357-25-867600. Corresponding author Sandhya Gangadhar is a freelance consultant ([email protected]).

You May Also Like