Voices of Biotech

Podcast: MilliporeSigma says education vital to creating unbreakable chain for sustainability

MilliporeSigma discusses the importance of people, education, and the benefits of embracing discomfort to bolster sustainability efforts.

March 1, 2013

As children growing up, we could barely contain our anticipation for those banner, milestone years: entering first grade, becoming a teenager, turning 16 and then 18, high-school graduation. But even the most innocuous “in-between” years saw notable change and maturation, and 2012 was just such a year for the growing cell therapy sector. Although it is not likely to be noted as a pivotal or breakthrough year, 2012 nonetheless delivered some significant and welcome signposts of continued sector maturation.

Here is a summary of what I believe to be the most notable of such events. I’ve liberally borrowed from the annual “Top 10” list delivered in January by Edward L. Field, chief operating officer of Cytomedix, Inc. and an executive committee member of the Alliance for Regenerative Medicine. He presented his list — voted on by the attending conference goers — in Washington, DC at Phacilitate’s Cell and Gene Therapy Forum (www.cgt-forum.com) held at the end of January 2013.

Perhaps the highest-profile event of 2012 was the awarding of the Nobel prize in Physiology or Medicine to Shinya Yamanaka and John B. Gurdon for their work in cellular reprogramming with induced-pluripotent cells. In some ways, this is certainly the pinnacle of recognition for the cell therapy sector. But it was voted the #2 event of the year by voters for the Phacilitate Top-10 list, perhaps because it is, as yet, a scientific but not clinical achievement.

The other unique event of the year was the ruling of the US District Court for the District of Columbia in favor of the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in litigation between Regenerative Sciences, LLC and the agency. An appellate court granted the FDA’s motion for summary judgment and issued a permanent injunction against RSI pertaining to the particular Regenexx procedure that was the subject of both the case and an FDA action more than two years before. At its essence was the issue of whether the agency can regulate a product that uses a patient’s own cells but is manufactured by that patient’s physician(s) in such a way as to — according to the FDA — cross the line between “practice of medicine” and “drug manufacturing.” This was voted as the 10th most important event of year in the Phacilitate poll (out of 16 nominations) and probably made the list because of the significant commercial implications no matter which way the verdict went.

I divide the rest of the year’s notable events into four categories below: product approvals, finance, corporate deals, and clinical data. The order reflects what I believe to be their relative importance this year.

Product Approvals

Before we review the 2012 cell therapy approvals, honorable mention must be given to the European Medicine Agency’s (EMA’s) approval of Glybera gene therapy from UniQure in Amsterdam, The Netherlands. Despite the many differences among gene, cell, and tissue therapy products, many investors and pharmaceutical companies class them together into the same kind of risk and innovation category, all under “regenerative medicine.” A product approval within that category tends to buttress support for all such products. Certainly I can attest to anecdotal evidence that the EMA’s long-awaited approval of a gene therapy suggests that even skeptics are acknowledging that we’ve moved a few notches forward along the continuum of regenerative medicine acceptance.

Regarding cell therapy approvals, it must be noted that no such products were approved by any regulatory agency for a good part of the 2000 decade (2002–2008). The floodgates have opened since, with 11 cell therapy products approved from 2009 through 2012 (excluding the more than 10 brought to market in regulated jurisdictions that, by virtue of their composition and intended use, require no formal approval before legal commercial distribution).

Six of those 11 cell therapy products approved in the past four years were approved in 2012. These included

FDA approval of the Organogenesis product called Gintuit as well as two cord-blood transplant products (Ducord from Duke University and HPC cord blood from ClinImmune Labs)

regulatory approval of Prochymal stem cell therapy by Osiris in both Canada and New Zealand

the South Korean KFDA’s approval of Cupistem and Cartistem stem cell therapies by Anterogen and Medipost, respectively.

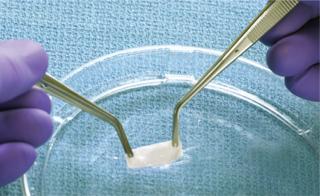

United States: In March, the FDA announced that it had approved Organogenesis’ cell-based product made of allogeneic human cells (from a donor unrelated to the patient) and bovine collagen for topical (nonsubmerged) application to a surgically created vascular wound bed in treating mucogingival conditions in adults. The FDA release describes Gintuit cell therapy as “a cellular sheet that contains allogeneic human cells and bovine collagen for topical application in the mouth. Gintuit consists of two layers. The upper layer is formed by human keratinocytes (the primary cell type in the skin’s outer layer) and the lower layer is constructed of bovine-derived collagen, human extracellular matrix proteins, and human dermal fibroblasts (skin cells that generate connective tissue).” What’s interesting is that the core product here is the same as what’s in Organogenesis’ Appligraf product, of which in 2012 the company surpassed the threshold of 500,000 units shipped.

The two other biologics license applications (BLAs) approved by the FDA in 2012 were issued to public cord banks for the allogeneic use of umbilical cord blood-derived stem cell products known as Ducord and HPC. They are both indicated for “use in unrelated donor hematopoietic progenitor cell transplantation procedures in conjunction with an appropriate preparative regimen for hematopoietic and immunologic reconstitution in patients with disorders affecting the hematopoietic system that are inherited, acquired, or result from myeloablative treatment.” The former brand is owned by Duke University’s School of Medicine, and the latter is owned by Clinimmune Labs, which is the University of Colorado’s cord blood bank. The fact that product approvals are being issued to nonindustry sponsors is an awkward artifact of a regulatory framework attempting to incorporate products that were brought to the market as medical practice before the regulation existed.

Use of cord blood is a well-established medical tradition for dozens of indications. Consequently, the FDA decided to lump those indications together into one BLA using the “unrelated donor hematopoietic progenitor cell transplantation procedures” language cited above. For new indications that fall outside that language, individual BLAs will have to be sought in the traditional fashion either by the banks themselves or (more likely) by companies using cord blood units they provide as raw materials for a unique product. Many (but not all) cord blood banks have now submitted BLA applications for unrelated donor hematopoietic progenitor-c

ell transplantation procedures, but only three such approvals have been granted to date.

Canada and New Zealand: Osiris Therapeutics has had more than its fair share of failed late-stage clinical trials in testing the Prochymal cell-based product for multiple indications. But the company eked out what most people would agree is a significant industry milestone if a very limited commercial victory with Canadian and New Zealand product approvals for pediatric graft versus host disease (GvHD) under certain conditions. I call this “significant” because Canada’s approval was the first regulatory approval of a stem-cell product in the Western world. It may, however, be a pyrrhic victory because the total market in these two countries represents a very small number of patients (probably <100 per year cumulatively). The product is based on allogeneic, bone-marrow–derived mesenchymal stem cells.

South Korea: The South Korean KFDA approved Anterogen’s and Medipost’s stem cell products in 2012. Anterogen’s Cupistem autologous, adipose-derived cell therapy is approved for treatment of anal fistulas suffered by patients with Crohn’s disease — an approval reportedly based on a trial involving 33 treated patients. Medipost’s Cartistem allogeneic, umbilical-cord–blood derived cell therapy is approved for treatment of damaged knee cartilage. Its approval is reported to have been based on a trial involving 89 patients. As of January 2013, Medipost claims to have treated 250 patients with the product even though it is not yet reimbursed.

The KFDA’s regulatory practices are criticized by some industry experts as being too permissive and lacking in transparency. The agency’s first cell therapy approval — indeed, the first-ever approval of a stem cell product anywhere — was for Pharmicell’s Heartcellgram-AMI treatment for heart attacks. Comprising cultured, autologous bone-marrow–derived mesenchymal stem cells, the product was tested in a trial involving 59 patients before KFDA approval. The framework and processes that the KFDA has created are generally structured similarly to that of top-tier regulatory bodies around the world. But criticisms center on the fact that the agency has approved cell-based products based on a data set from studies involving far fewer patients than would have been acceptable by others, as well as a lack of peer-reviewed publication of data produced by those trials. And it is almost certainly true that the US FDA, for example, would be unlikely to approve a product tested in so few patients. It is interesting to note that, according recent statements from Medipost, the data were sufficient to easily obtain clearance for a phase 2 trial in the United States. But the FDA did require the company to commit to addressing a lack of patient diversity in the data.

Other experts argue that with the safety profile of cell-based products, the KFDA’s speedy approvals and emphasis on postapproval trials and/or follow-up is a perfectly rational (although different) way to balance the risk-benefit analysis that every agency faces. From a patient perspective, it has the benefit of providing access to products far sooner than is found in other regulated jurisdictions.

Finance

Burrill and Company reports that biotech companies on the whole raised about US$71 billion in 2012. The Cell Therapy Group blog (www.celltherapyblog.com) reports that cell therapy and cell-based regenerative medicine companies raised just over $1.2 billion in the same time. Although 25% of this money came from grant sources, over $900,000 million was raised from investors. There is no baseline historical data to compare for determining whether this is a milestone, but most analysts and industry insiders believe that it is undoubtedly an industry first.

Companies that raised $25M or more from investors in 2012 include Fibrocell Sciences, Advanced Cell Technology, Aastrom Biosciences, Allocure, China Cord Blood Bank, Vital Therapies, Promethera Biosciences, Argos Therapeutics, Coronado Biosciences, Histogenics, and bluebird bio. Companies that raised a similar amount from grant sources include Cytori Therapeutics, Cellerant, and Stem Cells Inc. The first two sourced their grants from the US Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority (BARDA), within the federal government’s Office of the Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response, and the latter received two grants from the California Institute of Regenerative Medicine (CIRM). That last item is notable evidence of a significant pivot by CIRM last year in terms of its future funding focus. In 2012, that state organization provided $80M in funding to cell therapy companies. From that, we should expect to see a similar commitment to funding more industry-sponsored clinical work in the coming years than has been true in the past.

Finally, it is of note that an index of public cell therapy companies significantly outperformed the major stock indices (S&P 500, Dow Jones, and NASDAQ) in 2012. This might not be surprising for a year in which the major biotech indices significantly outperformed those three. Not only did the cell therapy index do just as well, however, but by some accounts it even beat out the NASDAQ biotech index in 2012. Go online to www.celltherapyblog.com to find the index definition and reporting.

Corporate Deals

There were five notable corporate deals in 2012. Each is significant for different reasons.

Commitment: Although it is not the biggest agreement in terms of monetary upfront payment, the one that the Phacilitate audience voted #1 was a landmark deal between Novartis and the University of Pennsylvania. In August, they announced an exclusive global research and licensing agreement to study, develop, and commercialize novel cellular immunotherapies using chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) technologies. In exchange for an at least $20 million commitment, Penn granted Novartis an exclusive worldwide license to the technologies used not only in an ongoing trial of patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), but also in future CAR-based therapies developed through the same collaboration.

As further evidence of its commitment to something more than an interesting academic research alliance, Novartis announced in December that it had purchased Dendreon’s New Jersey facility for $43 million and committed to keeping 100 of its 300 employees. It is widely assumed that the primary driver for that purchase was to provide the kind of uniquely designed infrastructure required for autologous cell therapies such as those expected to come out of the collaboration with Penn. This deal is both evidence of and further catalyst for a pendulum swing toward immunotherapies. It has encouraged venture capitalists that such therapeutics may have a pharmaceutical company “exit” after all — and, in typical fashion, heightened the competitive curiosity of other big-pharma companies in evaluating such products. One of the most significant impacts of the deal may be the confidence it instills in autologous cell therapies as bona fide pharmaceutical products despite repeated concernes that are voiced about the “business model.”

Big Buy: Without question the largest deal of the year was the acquisition of Healthpoint by Smith & Nephew for $782 million. Although Healthpoint’s current portfolio does not include a cell therapy product, it is a company with products in the “bioactives” and regenerative-medicine market. Its pipeline includes a cell therapy as lead product: HP802-24 (an allogeneic living-cell bioformulation containing keratinocytes and fibroblasts), which is currently entering phase 3 trials for treatment of venous leg ulcers. The price tag for this acquisition was very similar to that of the purchase price paid for Advanced BioHealing by Shire Pharmaceuticals in 2011. Healthpoin

t is forecast to generate some $190 million sales in 2012. That was roughly ABH’s annual revenue at the time of the sale. With very similar multiples for both deals, this creates a valuation metric for companies to consider in future deals.

Biobucks: Although another deal involved very little up-front payment (described as “single-digit millions”), Shire’s acquisition of certain clinical assets from Pervasis Therapeutics was notable. It confirmed that Shire is indeed serious in reorganizing its global organization into three business units, of which regenerative medicine is one, and that cell therapies will play an important role in that business unit. The deal itself was made up largely of what the industry has come to label as “biobucks”: back-end–loaded payments of up to $200 million to be made on passing certain development milestones and commercial thresholds.

Doubletake: One 2012 deal that, in my opinion, failed to get the attention it deserves was the Cytomedix acquisition of Aldagen. With a fairly broad pipeline and a growing set of phase 2 data, Aldagen had been shopping for further investment since at least 2008. Twice (first in 2008, then again in 2010) the company had filed for an initial public offering (IPO) to access the public markets, but both times the company pulled out citing “unfavorable market conditions” as the reason. As it began to cast its net wider and wider for increasingly creative deals, Aldagen fell into discussions with Cytomedix, a public company with a “regenerative medicine” focus built around platelet-rich plasma (PRP) devices and looking to bring in the kind of deeper, broader, and higher-value pipeline of products that Aldagen represented.

The deal was structured largely as a share swap in which existing Aldagen shareholders landed 17% of Cytomedix up front while existing Cytomedix investors agreed to buy $5 million more shares in it to help fund a phase 2 study of Aldagen’s lead stroke treatment. If that trial succeeds, Aldagen investors stand to earn the majority of 20 million Cytomedix shares held out in milestones.

What’s interesting about the newly combined company’s strategy is that the management has designed, negotiated, and is now implementing two product development initiatives. Those are intended to generate meaningful clinical data and move the cell therapies forward through significant milestones in a way that requires very little of the company’s own capital. The first stems from some other notable news Cytomedix received in May from the US Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) by way of a preliminary decision that the company’s AutoloGel PRP product will be covered for treatment of chronic nonhealing diabetic, venous, and/or pressure wounds. In a national coverage determination (NDC) memo, CMS proposed that coverage through its Coverage with Evidence Development (CED) program. So CMS will reimburse for use of the product in a registry-based protocol designed with its approval to answer questions and provide the evidence it requires to finalize its ruling. Company insiders have been quoted as saying that CMS reimbursement will almost entirely cover the total cost of the trial.

On the Aldagen side of the new business, Cytomedix announced in December it had signed an agreement with the US National Institutes of Health (NIH) to collaborate on a phase 2 clinical study of patients with intermittent claudication (caused by peripheral arterial disease). This study is funded by NHLBI/NIH and managed by the Cardiovascular Cell Therapy Research Network (CCTRN), which is also responsible for enrolling patients. The CCTRN network includes seven centers in the United States with experience and expertise in stem-cell clinical trials studying treatments for cardiovascular heart diseases. The phase 2, 80-patient, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial has already received investigational new drug (IND) clearance from the FDA and is expected to begin enrollment during the first quarter of 2013. Cytomedix will be responsible for manufacturing ALD-301 for the clinical trial and retain certain rights to data generated during the trial.

Good News, Bad News: When Osiris Therapeutics announced its collaboration with Genzyme in 2008 — in what was loosely described as a potentially $1 billion deal for the joint development and commercialization of Prochymal and Chondrogen products — their deal was understandably the toast of the industry. When Sanofi acquired Genzyme, and after the dust settled, it appeared that Sanofi was going to keep the cell therapy products and programs not only within Genzyme, but also would retain the deal with Osiris. And the industry quietly heralded what many people saw as a validation of cell therapy’s potential and fit within the Sanofi strategy.

But the industry preferred not to notice when that Osiris collaboration was quietly announced to be formally over this year. That followed a somewhat public battle about whether a statement buried in one of Sanofi’s securities filings about abandoning the program constituted functional termination of the agreement. Osiris spun that news as positive in that it had already benefited from tens of millions of Genzyme’s dollars and was now free to go it alone or seek another partner. And both Genzyme and Sanofi have been relatively quiet. The good news from the wider industry perspective is that Sanofi is still in the cell therapy game with Genzyme’s portfolio.

Clinical Data

Although 2012 will not go down as a year in which clinical data — either positive or negative — played a notable role, some results were published: phase 1 and interim results for central nervous system (CNS) and eye disorders from Advanced Cell Technologies, Stargardt’s disease from Lancet, Pelizaeus-Merzbacher disease from StemCells, Inc., amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS, Lou-Gehring’s disease) from NeuralStem, Inc., and dry macular degeneration from Johnson and Johnson. Early stage data were released and/or published from a few other companies. This is all meaningful to those companies involved in cell therapy development (as well as their investors and patients). But at a high level (from the industry’s overall perspective), those are all early stage data based on small numbers of patients. So they might be an early sign of something significant, but the data overall were nothing one would describe as a breakthrough — as yet.

Growing Up, Settling Down

The year 2012 will not be remembered as one of breakthrough change for the cell therapy industry. But it might have delivered us something the sector has sought the most: signs of an emerging maturity.

About the Author

Author Details

Lee Buckler is managing director of the Cell Therapy Group, a division of CTG Consulting, Co.; 1-877-760-1966, 1-778-278-6311; [email protected]; www.celltherapygroup.com

You May Also Like