The Biosimilars Action Plan: Promoting Faster and More Extensive Adoption of Biosimilar DrugsThe Biosimilars Action Plan: Promoting Faster and More Extensive Adoption of Biosimilar Drugs

December 8, 2021

WWW.ISTOCKPHOTO.COM

The pace with which biosimilar drugs have been adopted in the United States has frustrated (and displeased) policymakers (1). After passage of the Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act (BPCIA) (2) as part of the Affordable Care Act of 2010 (3), policymakers intended and expected significant reductions in expenditures for this class of biopharmaceuticals (4). The Federal Trade Commission (FTC) had predicted that the percentage of savings would be lower than that of the <90% reduction in costs for small-molecule generic drugs (5, 6). That this has not been the case provides the policy motivation for a joint effort by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the FTC to achieve that goal.

Biopharmaceuticals emerged in the latter part of the 20th century, due in large part to the recombinant DNA revolution that sparked the biotechnology industry (7). Although some drugs that fell within the scope of the definition of a biologic drug already were known (insulin isolated from a variety of animal species, for example) (8), many of those products suffered from problems with antigenicity; that is, human immune systems recognized them as foreign sooner or later (9), and processes to scale them for commercial use were relatively inefficient (10). Starting in the 1980s, successes in biotechnology-produced human-derived biologic drugs had dramatic effects at treating life-threatening diseases. Those successes included Humulin (insulin, Lilly, 11), Intron A (interferon, Schering, 12), tissue plasminogen activator (an anticlotting drug from Genentech, 13), HGH (human growth hormone, Lilly, 14) and EPO (erythropoietin, Amgen, 15). Following those early achievements were drugs for treating cancer, such as Herceptin (trastuzumab, Genentech, 16); for ameliorating the deleterious effects of conventional cancer chemotherapies such as with Neupogen (filgrastim, Amgen, 17); and for addresssing other chronic diseases, such as Humira (adalibumab, from AbbVie) for rheumatoid arthritis. Today, biologic drugs make up the majority of best-selling (and most expensive) drugs on the pharmaceutical market (18, 19).

The costliness of biologic drugs stems from the complexity in developing them for commercialization, regulatory approval, and manufacturing (10). Unlike conventional small-molecule drugs that are made using (relatively) inexpensive methods for chemical synthesis, biopharmaceuticals must be made in living cells, initially in bacteria, but now commonly in immortalized mammalian cell lines (20). Even when reduced to routine commercial synthesis, such biologic production methods factor heavily into the high costs of most biologic drugs (10). High biopharmaceutical drug prices frequently have spurred policymakers to seek regulatory avenues for producing “generic” versions of biologic drugs. But because of the same complexities that distinguish biopharmaceuticals from small-molecule drugs, making an exact, “generic” copy of a biologic drug is functionally impossible (21). Accordingly, the best that can be achieved are so-called biosimilars.

The US passage of the BPCIA permitted biosimilars to be made, approved, and marketed for the first time. The act contains two sections. The first section sets forth the regulatory basis for biosimilar drug approval, and the second establishes a complicated scheme for settling patent disputes (the patent dance) between biologic drug innovators (called reference product sponsors in the act) and biosimilar applicants (2). The regulatory portions of the act delegate determination of most of the requirements to the FDA. In the years following enactment, the agency issued a number of guidance documents regarding what would be considered sufficient evidence that a proposed biosimilar was “similar enough” for approval (see the “FDA Guidances” box). It is important to note that the agency’s guidances provide detailed requirements and evidence cited for biosimilar drugs in other jurisdictions (principally Europe, which had introduced a biosimilar pathway almost a decade before the United States) (22).

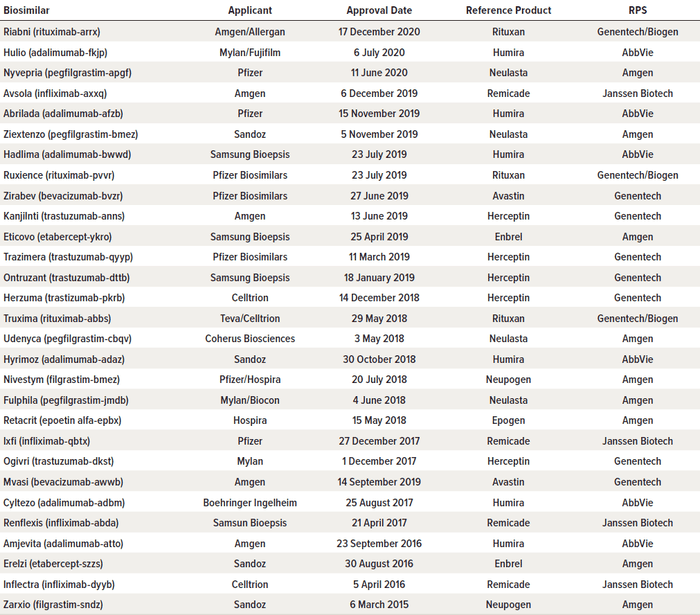

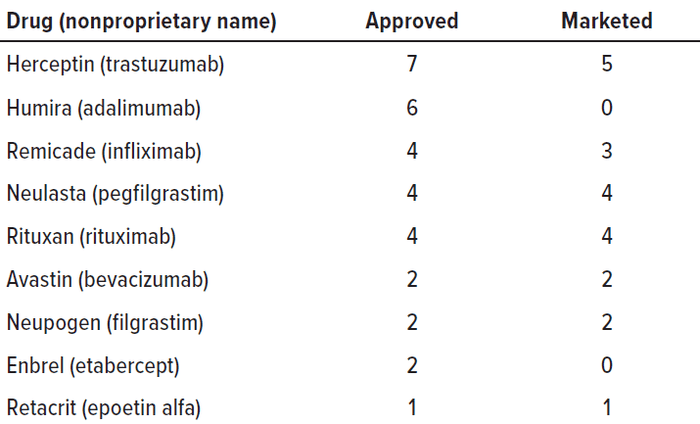

The consequence of these legislative and regulatory activities is that as of December 2020, 29 biosimilars have received FDA approval (Table 1) (23). However, approval of such drugs is limited to the innovator products to which they are biosimilar. As shown in Table 2, they can be used in place of nine such innovator biologics, but only 20 of them have been marketed. For Enbrel and Humira products, there are as yet no marketed biosimilars. In addition, there has been some resistance from physicians and other prescribers to adopting biosimilars (due in large part to their complexities, the severity of the illnesses they treat, and the involvement of medical personnel in delivering those treatments) (24). These circumstances have produced a clarion call from members of Congress and commentators that more must be done to increase availability and acceptance of biosimilars (25–27). In response, the FDA and FTC, two agencies involved in drug approval and price regulation, announced the “Biosimilars Action Plan (BAP): Balancing Innovation and Competition” on 3 February 2020 (28). The initiative is intended “to ensure that this balance between innovation and competition exists across the spectrum of pharmaceutical products.” The hoped-for outcome of the BAP is that “[a]fter patents or other exclusivities expire on these novel products, prices can fall dramatically once follow-on products are available, potentially lowering costs for patients and payers and expanding access to these innovations” (28).

Table 1: As of December 2020, 29 biosimilar drugs have received approval from the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA). (RPS = regulated product submission)

Table 2: Approvals of biosimilars are limited to the biologic drugs to which they are biosimilar. Currently such products can be used in place of nine innovator biologic drugs, but only 20 of them have been marketed. The Enbrel and Humira reference products as yet have no marketed biosimilars.

Some of the bureaucratic measures the agency intends to implement to further these efforts include the following:

• introducing new FDA tools to improve efficiency of FDA review (e.g., templates “tailored to marketing applications for biosimilar and interchangeable products”)

• creating information resources and development tools for biosimilar applicants (in silico models and simulations for correlating pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic (PK/PD) responses to clinical outcomes)

• enhancing The Purple Book database (see corresponding box, above)

• exploring data-sharing agreements with foreign regulators

• establishing a new Office of Therapeutic Biologics and Biosimilars (OTBB) to improve coordination under the Biosimilar User Fee Amendments (BsUFA) program

• providing critical education to healthcare professionals

• finalizing the guidance on labeling (29)

• providing finalized guidance on interchangeable biosimilars (30)

• improving analytical approaches for structure/function for demonstrating biosimilarity, including statistical methods

• implementing standards for manufacturing quality control

• improving public dialog with hearings and requests for public input on FDA actions to evaluate and promote biosimilars.

The FDA maintained that “[t]his is a crucial time in the emergence of the marketplace of biosimilar and interchangeable products.” The agency expects continued expansion of the number of approved biosimilar and interchangeable products in the coming years. The announcement of this new initiative recognizes “barriers to marketing a biosimilar or interchangeable product that are outside of the FDA’s purview” but asserts that it is part of the agency’s mandate to “advance[e] policies to facilitate the efficient development and approval of these products.”

Key Elements of the BAP

The four key elements of the BAP focus on improving the efficiency of biosimilar approval; maximizing scientific and regulatory clarity; communicating effectively with patients, clinicians, and payers; and supporting market competition.

Improving the Efficiency of the Biosimilar and Interchangeable-Product Development and Approval Process: Improving coordination with the Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER) is a key aspect of improving the overall process. The availability of application review templates that are formatted for 351(k) biologics license application (BLA) requirements will serve as another means of improving efficiency. Within the FDA, the transition to a Therapeutic Biologics and Biosimilars Staff (TBBS) from the Office of New Drugs (under CDER) to the OTBB is intended to “improve coordination and support” of activities under the BsUFA, increase agency response times, and improve efficiencies in policy development and responses to applicants. Information resources will be developed for biosimilar applicants such as an index of critical quality attributes for comparing reference products to biosimilars, along with comparison metrics that to help reduce the size of clinical studies

Maximizing Scientific and Regulatory Clarity for the Biosimilar Product- Development Community: The FDA expects continued publication of guidances for industry (17) to be forthcoming, involving public hearings and prioritizing the following issues.

Final or Revised Draft Guidance: Reference Product Exclusivity for Biological Products Filed Under Section 351(a) of the Public Health Service (PHS) Act (31);

Final or Revised Draft Guidance: Implementation of the “Deemed to be a License” Provision of the Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act of 2009 (32);

Final or Revised Draft Guidance: Statistical Approaches to Evaluate Analytical Similarity (33);

Draft Guidance: Processes and further considerations related to postapproval manufacturing changes for biosimilar biological products as part of the US Biosimilar Product Development (BPD) program (34).

The agency also is developing guidance for biosimilar applicants who will seek approval for fewer than all conditions for which a reference product is licensed. It is developing a formal rule for interpreting the definition of biological product under the BPCIA to provide additional “clarity.” The FDA is evaluating regulations regarding BLA submissions and working on an enhanced Purple Book (that will contain “information about newly approved or withdrawn BLAs and about reference product exclusivity determination”).

Finally, under this part of the BAP, the agency will be “[s]trengthening its partnerships with regulatory authorities in Europe, Japan and Canada” by “harmonizing requirements for their development as well as sharing regulatory experience across national boundaries.” That includes data sharing agreements to increase the use of non–US-licensed comparator products to support biosimilar application.

Developing Effective Communications to Improve Understanding of Biosimilars Among Patients, Clinicians, and Payers: This portion of the BAP is aimed at increased educational efforts according to the Biosimilar Education and Outreach Campaign released in October 2017. Those efforts include providing videos, webinars, and information on the webpage and educational materials for patients, pharmacists, and other stakeholders.

Supporting Market Competition By Reducing Gaming of FDA Requirements or Other Attempts to Delay Competition Unfairly: In many ways the most provocative part of the plan, the announcement states the following:

The FDA will clarify our position on issues affecting reference product exclusivity to better effectuate balance between innovation and competition. We will also take action, whenever necessary, to reduce gaming of current FDA requirements, and coordinate with the Federal Trade Commission to address anti-competitive behavior. Additionally, we will work with legislators, as needed to close any loopholes that may effectively delay biosimilar competition beyond the exclusivity periods envisioned by Congress. (35)

The FDA intends to take steps for biosimilars analogous to those of the Drug Competition Action Plan (DCAP), which the agency implemented for generic drugs. For that category of products, it was “a priority to address practices that delay or block competition from entering the market (35).” Those efforts were aimed at preventing branded drug makers from activities such as “refusal to sell the samples necessary for developing generic drugs [a practice we’ve seen with products under limited distribution, whether the drug maker limits distribution voluntarily or does so in connection with a Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS) program]” (35). Insofar as such practices are being used by reference product sponsors (and the announcement does not provide examples of such behavior), the agency states that “[w]e will apply the same principles used in DCAP to our BAP to address circumstances in which drug makers refuse to sell samples, or use any other anticompetitive strategies, to delay the entry of biosimilar or interchangeable development and competition” (35).

The FDA says that it expects development of biosimilar and interchangeable drugs to “continue to evolve” and, thus, that implementation of the BAP will be “dynamic.”

Following in this vein, on 3 February 2020, the FDA and FTC issued a joint statement (36) aimed at advancing competition in the biologic drug market, restating some of the goals enunciated in the action plan:

• The FDA and FTC will coordinate to promote greater competition in biologic markets.

• The FDA and FTC will work together to deter behavior that impedes access to samples needed for the development of biologics, including biosimilars.

• The FDA and FTC intend to take appropriate action against false or misleading communications about biologics, including biosimilars, within their respective authorities.

• The FTC will review patent settlement agreements involving biologics, including biosimilars, for antitrust violations.

Although a good deal of this announcement is conventional bureaucratic promotion, a few nuggets suggest that the FDA might be becoming more confrontational and aggressive toward perceived “bad behavior” by certain shareholders. It is certainly the case that the price of drugs, particularly biologic drugs, is high and imposes a significant cost burden on the healthcare system as a whole, both public and private. The BAP appropriately addresses such concerns and recognizes that they must be addressed. But it is also good to try to understand the economic realities that have created the situation (without excessive and unproductive finger-pointing). It is a truism that everything has increased in price (and many things have even adjusted for inflation). After all, it isn’t just the elderly that are confronted with prices that seem ridiculously excessive. But for drugs, policymakers and the public both must recognize that the low-hanging fruit of small-molecule drugs and those with (relatively) simple etiologies were discovered in the first flowering of modern pharmaceutical intervention in human disease (37, 38). And federal regulation, particularly by the FDA, is more extensive and costly than it was before the thalidomide tragedy in 1962. Although it is convenient and politically expedient to castigate the pharmaceutical industry for high prices, it is foolhardy not to recognize those and other factors behind the current price situation.

The comments in the FDA’s BAP also include statements by former FDA commissioner Scott Gottleib (39) regarding the possibility of changing US drug importation regulations (but with disclaimers regarding exclusivities and “supply chain disruptions” to soften the political effects of implied threat) to permit “temporary” importation of drugs from foreign sources. The FDA has also created a task force (40) to address drug shortages, due either to supply-chain difficulties or source monopolization of sole-sourced unpatented drugs without remaining regulatory exclusivity.

But another point is typically overlooked. For many biologic drugs, the diseases they address are ones that a generation ago resulted in significant morbidity and mortality; indeed, some diseases were invariably fatal (many cancers and HIV) or severely debilitating (kidney disease and hepatitis). Some of those were diseases of the elderly, and the wisdom of expending vast sums to extend lives for short times is a topic for another day. But for the overwhelming number of cases in which individuals in the prime of life are cured or their diseases can be managed, such drugs provide significant advantages, both for the afflicted individuals and society as a whole. In the most hard-hearted, dollars-and-cents analysis, what pundits who bemoan high drug costs appear to forget is that individuals can be returned to the workforce as productive participants who hold down jobs, pay taxes, and participate in the US consumer economy. Society, whether in the form of local or nationwide businesses or federal, state, and local tax collectors, reaps the benefit of those who have returned to the workforce thanks to the effects of biopharmaceuticals that did not exist 20, 10, or five years or even one year ago.

And that doesn’t take into account the human benefits. Individuals (and their spouses, children, and grandchildren) can enjoy the benefits of longer life and participation in weddings, births, and other lifetime milestones. Undue focus on the goal — obtaining biopharmaceuticals at reduced prices — risks delaying availability of those therapies and their benefits through frustration of private investors and the government’s generally poor track record of innovation. It would be well for policymakers, particularly at FDA, to keep such considerations in mind to temper their fiscal zeal.

References

1 Biosimilars. US Food and Drug Administration: Silver Spring, MD, 28 July 2021; https://www.fda.gov/drugs/therapeutic-biologics-applications-bla/biosimilars.

2 42 USC 262. Regulation of Biological Products. United States Code 7 January 2011; https://www.govinfo.gov/app/details/USCODE-2010-title42/USCODE-2010-title42-chap6A-subchapII-partF-subpart1-sec262.

3 Affordable Care Act. Wikipedia 15 September 2021; https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Affordable_Care_Act.

4 Noonan KE. A Solution in Search of a Problem. Patent Docs 26 March 2019; https://www.patentdocs.org/2019/03/a-solution-in-

search-of-a-problem.html.

5 Emerging Health Care Issues: Follow-on Biologic Drug Competition. US Federal Trade Commission: Washington, DC, 2009; https://www.ftc.gov/sites/default/files/documents/reports/emerging-health-care-issues-follow-biologic-drug-competition-federal-trade-commission-report/p083901biologicsreport.pdf.

6 Noonan KE. No One Seems Happy with Follow-On Biologics, According to the FTC. Patent Docs 14 June 2009; https://www.patentdocs.org/2009/06/no-one-seems-happy-with-followon-biologics-according-to-the-ftc.html.

7 Hughes SS. Genentech: The Beginnings of Biotech. University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, 2011.

8 Animal Insulin. Diabetes.co.uk 15 January 2019; https://www.diabetes.co.uk/insulin/animal-insulin.html.

9 What Are the Major Drawbacks of Using Insulin Purified from Animals? Diabetes Talk 26 December 2017; https://diabetestalk.net/insulin/what-are-the-major-drawbacks-of-using-insulin-purified-from-animals.

10 Makurvet FD. Biologics vs. Small Molecules: Drug Costs and Patient Access. Med. Drug Disc. 9, 2021: 100075; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.medidd.2020.100075

11 Quianzon C, Cheikh I. History of Insulin. J. Community Hosp. Intern. Med. Perspect. 2(2) 2012; https://doi.org/10.3402/jchimp.v2i2.18701.

12 Recombinant Drugs. National Museum of American History. Smithsonian: Washington, DC, 2021; https://americanhistory.si.edu/collections/object-groups/birth-of-biotech/recombinant-drugs.

13 Press release: Tissue Plasminogen Activator (tPA) Produced By Recombinant DNA Techniques. Genentech: South San Francisco, CA, 21 July 1982.

14 Fryklund LM, Bierich JR, Ranke MB. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 15(3) 1986: 511–535; https://doi.org/10.1016/s0300-595x(86)80009-3.

15 Ohls RK, Christiansen R. Recombinant Erythropoietin Compared with Erythrocyte Transfusion in the Treatment of Anemia of Prematurity. J. Pediatr. 119(5) 1991: 781–788; https://doi.org/10.1016/s0022-3476(05)80303-8.

16 Shepard HM, et al. Herceptin. Therapeutic Antibodies: Handbook of Experimental Pharmacology, Volume 181. Chernajovsky Y, Nissim A (Eds.). Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2009; https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-540-73259-4_9.

17 Neupogen (Filgrastim): General Information for the Public. US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Atlanta, GA, 4 April 2018; https://www.cdc.gov/nceh/radiation/emergencies/neupogenfacts.htm.

18 Noonan KE. Drug Costs Continue to Rise. Patent Docs 3 March 2018; https://www.patentdocs.org/2018/03/drug-costs-continue-to-rise.html.

19 Noonan KE. Cancer Drug Costs Continue to Rise. Patent Docs 16 April 2019; https://www.patentdocs.org/2019/04/cancer-drug-prices-continue-to-rise.html.

20 Burke E. Biomanufacturing: How Biologics Are Made. Biotech Primer 16 June 2020; https://weekly.biotechprimer.com/biomanufacturing-how-biologics-are-made.

21 Waithe R. Why Biosimilars Are Not Generics. Medium 29 June 2018; https://medium.com/rxradio/why-biosimilars-are-not-generics-a25700348825

22 Biosimilars in the EU: Information Guide for Healthcare Professionals. European Medicines Agency: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/leaflet/biosimilars-eu-information-guide-healthcare-professionals_en.pdf.

23 Noonan KE. FDA Approves First Interchangeable Biological Product. Patent Docs 5 August 2021; https://www.patentdocs.org/2021/08/fda-approves-first-interchangeable-biological-product.html.

24 Inserro A. Uptake of Biosimilars in the US: Good News, Bad News. AJMC Center for Biosimilars 10 April 2019; https://www.centerforbiosimilars.com/view/uptake-of-biosimilars-in-the-us-good-news-bad-news.

25 Issacson AA. Two Bipartisan Bills Aim to Encourage Competition in the Biopharma Industry. JD Supra 25 May 2021; https://www.jdsupra.com/legalnews/two-bipartisan-bills-aim-to-encourage-8046419.

26 New Analyses Point to Opportunities to Increase Savings from Biosimilar Adoption. Biosimilars Council: Washington, DC, 25 March 2021; https://biosimilarscouncil.org/resource/savings-biosimilars-adoption.

27 Noonan KE. Senators Ask FTC to Investigate Biosimilar Litigation Settlement Agreement. Patent Docs 5 July 2018; https://www.patentdocs.org/2018/07/senators-ask-ftc-to-investigate-biosimilar-litigation-settlement-agreement.html.

28 Biosimilars Action Plan: Balancing Innovation and Competition. US Food and Drug Administration: Silver Spring, MD, 2018; https://www.fda.gov/media/114574/download.

29 Noonan KE. FDA Issues Guidance Regarding Biologic Drug Naming. Patent Docs 17 January 2017; https://www.patentdocs.org/2017/01/fda-issues-guidance-regarding-biologic-drug-naming.html

30 Noonan KE. FDA Issues Final Guidance Regarding Biosimilar Interchangeability. 13 May 2019; https://www.patentdocs.org/2019/05/fda-issues-another-draft-guidance-regarding-biosimilar-interchangeability.html.

31 Draft Guidance for Industry on Reference Product Exclusivity for Biological Products Filed Under Section 351(a) of the Public Health Service Act: Availability. US Fed. Reg. 5 August 2014; https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2014/08/05/2014-18169/draft-guidance-for-industry-on-reference-product-exclusivity-for-biological-products-filed-under.

32 Interpretation of the “Deemed to be a License” Provision of the Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act of 2009: Guidance for Industry. US Food and Drug Administration: Silver Spring, MD, December 2018; https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/interpretation-deemed-be-license-provision-biologics-price-competition-and-innovation-act-2009.

33 FDA Withdraws Draft Guidance for Industry: Statistical Approaches to Evaluate Analytical Similarity. US Food and Drug Administration: Silver Spring MD, 21 June 2018; https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-safety-and-availability/fda-withdraws-draft-guidance-industry-statistical-approaches-evaluate-analytical-similarity.

34 New and Revised Draft Q&As on Biosimilar Development and the BPCI Act (Revision 3): Draft Guidance. US Food and Drug Administration: Silver Spring, MD, December 2018; https://www.fda.gov/media/119278/download.

35 Press release: FDA Tackles Drug Competition to Improve Patient Access. US Food and Drug Administration: Silver Spring, MD, 27 June 2017; https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-tackles-drug-competition-improve-patient-access.

36 Cole C. Feds Unveil Collaborative Push on Biologics Competition. IPLaw360, 3 February 2020; https://www.law360.com/articles/1239961/attachments/0.

37 Epstein RA. Overdose: How Excessive Government Regulation Stifles Pharmaceutical Innovation. Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, 2006.

38 Rosen W. Miracle Cure: The Creation of Antibiotics and the Birth of Modern Medicine. Penguin: New York, NY, 2017.

39 Gottlieb S. Statement by FDA Commissioner Scott Gottlieb, MD, on the Formation of a New Work Group to Develop Focused Drug Importation Policy Options to Address Access Challenges Related to Certain Sole-Source Medicines with Limited Patient Availability, But No Blocking Patents or Exclusivities. US Food and Drug Administration: Silver Spring, MD, 19 July 2018; https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/statement-fda-commissioner-scott-gottlieb-md-formation-new-work-group-develop-focused-drug.

40 Gottlieb S. Statement by FDA Commissioner Scott Gottlieb, MD, on Formation of a New Drug Shortages Task Force and FDA’s Efforts to Advance Long-Term Solutions to Prevent Shortages. US Food and Drug Administration: Silver Spring, MD, 12 July 2018; https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/statement-fda-commissioner-scott-gottlieb-md-formation-new-drug-shortages-task-force-and-fdas.

Kevin E. Noonan, PhD, is a partner with McDonnell Boehnen Hulbert & Berghoff LLP, 300 South Wacker Drive #3100, Chicago, IL 60606; [email protected].

You May Also Like