Cell and Gene Therapies Get a Reality Check: A Conversation with Anthony Davies of Dark Horse Consulting GroupCell and Gene Therapies Get a Reality Check: A Conversation with Anthony Davies of Dark Horse Consulting Group

Anthony Davies of Dark Horse Consulting Group hosted the super plenary at Phacilitate 2020 (www.phacilitate.co.uk)

As founder of cell and gene therapy (CGT) specialist firm Dark Horse Consulting Group in California, Anthony Davies speaks from a quarter century of experience including former positions at Onyx Pharmaceuticals, Syrrx, ZymeQuest, Serologicals, Geron Corporation, Capricor, and 4D Molecular Therapeutics — and he currently serves on the board of directors for TrakCel and the scientific advisory boards for Akron Biotech and BioLife Solutions. In his plenary address at the Phacilitate 2020 Leaders World conference (part of Advanced Therapies Week in Miami, FL), he reflected on difficulties the advanced-therapies sector has faced since its high of 2017, when three products achieved US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval: Kymriah (tisagenlecleucel) for Novartis, Yescarta (axicabtagene ciloleucel) for Kite Pharmaceuticals and Gilead Sciences, and gene therapy Luxturna (voretigene neparvovec) for Spark Therapeutics and Roche.

“A few years ago, I introduced this evening by saying: ‘Finally the field has had the year that we’ve been saying we are going to have for years.’ That was a great year,” he told a packed room at the Hyatt Regency Miami this past January. Kymriah and Yescarta chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapies offered treatment to “patients who previously could measure their life expectancy in a small number of months,” he added, and Luxturna gene therapy offered “hope to children whose ophthalmic deterioration was a statistical certainty.”

With those breakthroughs, positivity was high in the past few years. In January 2019, then FDA Commissioner Scott Gottlieb predicted in an agency statement that there would be more than 200 regenerative-medicine investigational new drug (IND) regulatory submissions in 2020 and that by 2025 the agency would be approving 10–20 CGT products each year (1). “I think 200 INDs is doable this year,” Davies said, “but INDs do not cure patients. And I think that if we’ve struggled with getting three commercial approvals in the years after that first year when three commercial approvals were made, then getting 10–20 [annually] in five years from now is going to be extremely challenging.”

Stalled Industry: Since that breakthrough year, the advanced-therapies industry has been hit by “bad news” and a lack of commercial products. Only Novartis/AveXis’s Zolgensma (onasemnogene abeparvovec-xioi) gene therapy and bluebird’s Zynteglo (autologous CD34+ cells encoding βA-T87Q-globin gene) cell therapy were approved by the FDA last year, while Takeda’s allogeneic cell therapy Alofisel (darvadstrocel) was “approved to a certain extent in Europe.”

Davies described the Zolgensma approval — with a price of US$2.1 million — as “groundbreaking,” but he noted that it has been overshadowed by a scandal involving data falsification during the approval process. He also noted that the Zynteglo success has been muted by multiple manufacturing problems that have delayed its launch. Meanwhile, the Kymriah pioneer product continues to suffer from manufacturing difficulties itself, and Novartis seems to be struggling with fixing those, as Davies suggested.

At the 38th JP Morgan Healthcare Conference in San Francisco, CA, just a few weeks before Phacilitate, Davies pointed out, “it was announced that for 10% of patients, no shipment of drug is made, and for a very significant minority of patients, shipment is made with out-of-specification product for which Novartis cannot charge.” He added that at that investor conference, Novartis CEO Vasant Narasimhan “said that they had made great progress in identifying the manufacturing issues and were negotiating their resolution with the FDA.” However, “this was exactly the same statement he made at JP Morgan the year before.”

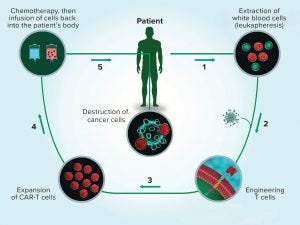

Figure 1: The multistep process of chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy reflects the complexity of cell therapy products overall. (www.istockphoto.com)

Reasons To Be Cheerful: Despite the slowdown in commercialization and manufacturing challenges, Davies said that much remains about which to be positive. “Everything I said reflects the extreme difficulty in bringing this class of therapeutics to market. If these therapeutics were easy to develop, then they would have been developed [already]. If diseases were easy to cure, then we wouldn’t need new therapeutics. Let us just use these good pieces of news and these bad pieces of news as inspiration. Let’s continually remind ourselves that what we do is one of the hardest things in science or medicine at this time.” Figure 1 illustrates his point.

Davies was not alone in his views. Speaking in Miami later that week, Robert Preti (CEO of Hitachi Chemical Advanced Therapeutic Solutions) admitted that the advanced-therapies industry is behind where he thought it would be by now when he began his career 37 years ago. But he also said that he was not too worried. “I want to commend this industry on what we have achieved for patients,” he said, noting the difficulty in developing and making CGTs. He also highlighted that with more than 1,000 regenerative therapies in development, problems eventually will be ironed out and these medicines will make the widespread impact intended in time.

Our Conversation

After the conference in January, we caught up with Davies for a little more discussion of major themes that had been brought up during the week’s program. We drew some inspiration for our questions from another plenary talk at Phacilitate 2020 (3).

On Trends: The plenary session seemed to provide something of a “reality check” this year, especially in regard to costs; chemistry, manufacturing, and controls (CMC); and product approvals. What’s happening in the industry right now that most gives you pause — and what gives you particular hope for the future?

Davies: On an empirical level, after three banner approvals in 2017, the number of cell and gene [biologics license applications] BLAs and [marketing authorization applications] MAAs has honestly been a disappointing anticlimax. It’s possible that BioMarin’s valoctocogene roxaparvovec gene therapy, with its [Prescription Drug User Fee Act] PDUFA date in August and no advisory-committee hurdle, will rejuvenate the field from this perspective. But I still feel that progression to commercialization has been somewhere between disappointingly slow and stalled.

On Approvals: You noted the unlikeliness of Gottlieb’s predicted 10–20 annual approvals in five years from 2019. At this point, what would you consider to be a more realistic prediction?

Davies: As of today, there have been just four cell and gene approvals on top of the dozen or so “legacy” approvals, some of which are products no longer on the market. These “next-gen” approvals were three in 2017, none in 2018, one in 2019, and none so far in 2020. And sadly, who believes that the COVID-19 pandemic will do anything but further slow this approval rate (2)? So we have had four approvals in the past three years. Even if that doubles for the next three — to a total of eight more by the end of 2022 — I will be profoundly disappointed. I will make an optimistic prediction that we will see a dozen approvals between now and the end of 2022, corresponding to four a year. If that prediction is correct, we might just scrape into the bottom end of Gottlieb’s range by 2025.

On Patents: The biotechnology industry is a notoriously complicated intellectual property (IP) landscape. CAR-T and clustered and regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR) technologies both raise patent conundrums. And some experts point to the “medical treatment methods” patentability exemption as limiting for many cell therapy approaches. Will these present obstacles to the industry’s progress? Or are they just “par for the course” in doing business? Do you know of upcoming cases we should watch?

Davies: Not in any way to belittle the IP field or process, but for decades the biotech industry has moved forward on the basis of crossing that bridge if and when we come to it. CRISPR is a great example of this. As the east coast versus west coast “[UC] Berkeley versus the Broad [Institute]” soap opera continues to enrich both organizations’ lawyers (4), no one really believes that these issues are going to prevent patients from receiving the benefits of this technology — if it actually does work in the sense of generating licensed products. So many other fields of equal promise and apparently universal application, such as antisense and siRNA, have disappointed in the scope of eventual approvals that there is built-in reluctance to assume that IP will ever gate anything in the real world.

On Mergers, Acquisitions, and Licensing: On that note, will licensing provide an answer or just another stumbling block? (Consider the complex web of licensing around protein expression systems.) Is gaining control of IP a major driver in mergers and acquisitions related CGTs?

Davies: We do not see such a complex web of licensing in CGTs as in the protein-production world. I think this reflects a reciprocal of the extreme complexity of the field. There are so many ways to tackle a problem and reverse-engineer almost everything. But I do believe that at some point there will be a level of collapse of this complexity. It most likely will not be around clever molecular or cellular IP, however; it will be around breakthroughs in the cost-effectiveness of manufacturing. As I commented at Phacilitate 2019, we are “sleep walking into a cost-of-goods (CoG) crisis.” Sadly, this is even truer today than it was last year. The companies that do crack that nut will be those that can effect the equivalent of taking monoclonal antibody (MAb) yields from milligrams to grams per liter of culture.

On In-House and Outsourced Manufacturing: Investment money currently is pouring into the CGT industry, and as a result we see a lot of facility construction by both product developers and service providers. Meanwhile, we heard a lot of talk at Phacilitate 2020 about a dearth of available talent. How will companies compete to fill those new facilities with skilled workers? Will outsourcing be less about capacity and more about capability in the foreseeable future?

Davies: Reports on the death of outsourced manufacturing have been greatly exaggerated, to misquote one of Mark Twain’s best quotations. Therapeutics developers are insourcing manufacturing because they can — although the macroeconomic effects of the CoVID-19 pandemic may considerably dampen enthusiasm for such capital projects. Who wouldn’t want to own that? But the answer to that question is someone whose drug fails in phase 3. Overbuild in biologics was curtailed by exactly that phenomenon, and sadly history is likely to repeat itself in this field. When that occurs, a number of therapeutics developers will pivot to being contract manufacturing organizations (CMOs) themselves. So there always will be customers for CMOs: capital-investment risk-averse therapeutics developers and those who simply cannot afford to build.

Talent shortage is another matter altogether. Again, the biologics industry suffered from and solved this problem in previous decades. The only way it happens is organically: as organizations grow, hire, and train, and eventually their ‘graduates’ disperse throughout the industry and have to be replaced, themselves. This is not to say that vocational training in higher education can’t help — and it can, greatly. We all should support far-sighted universities that step up to provide this sort of training.

On Clinical Results, Patients, and Access: Some companies are adding patient representatives to their boards of directors, and some experts suggest adding them to institutional review boards (IRBs) for clinical testing as well. Increasingly we hear patient voices in discussions about cost and clinical results. You included the patient perspective in your plenary session conversations. Can you speak here to the importance of patients in helping CGT companies find new business models and pathways to providing access?

Davies: If we don’t listen to patients, then we lose all perspective. On a personal level, I hear this patient perspective every day from my wife, who is a practicing oncologist at a large American medical center. The dinner-table conversation in our household can be sobering and heart wrenching. But ultimately that conversation also can be uplifting and optimistic: Patients want to live, they want to live well, and their doctors want nothing more than never to have to see them again — in the best possible way! This is the ultimate driver of everything we do, and shame on us if we ever forget.

On Costs: Under Medicare’s and other prescription-drug programs, patients are required to pay a percentage of the cost of their medicines. For some CGTs, that can add up to thousands of dollars out of pocket — something many patients simply cannot pay. In nationalized healthcare systems, however, that isn’t the case. Are CGT products more likely to make inroads where copays don’t present such obstacles to their adoption?

Davies: We are at risk of developing CGTs that are cost-effective but unaffordable. So the fundamental aspects of pricing must change. Performance-based pricing and amortization schemes are a good start, but they carry huge operational challenges, especially in the United States. Two examples include navigating with patients who change insurers and ensuring that patients comply with long-term efficacy assessments. Ultimately, as thought leaders have started to educate us, this is a risk-analysis problem that will be solved by relatively macroeconomic methods such as pure and mixed bundling and securitization. It will be essential to spread risk and allow investors in such pools to access suitably diversified portfolios. But in combination with the CoG reductions already discussed, in my opinion, tools such as that will solve the capital crisis that such expensive drugs are engendering.

On Quality By Design (QbD): QbD was glaringly absent from most talks in the manufacturing track at Phacilitate this year. Some gene-therapy speakers offered oblique perspectives on it, but there was very little from the cell-therapy developers. And although it’s true that good manufacturing practices (GMPs) don’t become as much an issue until products are in clinical trials, our friends in protein biopharmaceuticals have learned the hard way that it’s a good idea to start thinking about such things as early as possible in development. Do you think CGT companies will have to learn that lesson, too?

Davies: I completely agree that slow penetrance of concepts such as QbD into the cell and gene field is problematic. Unfortunately, few companies seem to have learned the hard lessons endured by the biologics field in past decades. (Editor’s Note: Find more in-depth discussion by Kim Bure et al. elsewhere in this issue.)

The Last Word

In relation to the QbD question, Davies also pointed out some problems with recent approvals that came from regulators’ CMC concerns. (Even a company as large and experienced as Novartis is having problems.) We wondered what message early stage companies need to hear now to improve their chances for success later on.

“Manufacturing processes must be ready for clinical production at phase 1,” said Davies, “and they must be ready for commercial production at the licensure-enabling trial, whether that is phase 3 or earlier.”

Technology providers can help (5). “One new trend we have seen over the past year is dramatically increased interest from private equity funds in tools and technology players in the cell and gene field,” Davies pointed out. “My colleague Katy Spink’s opinion piece at the end of last year identified 2019 as the year this ‘gold rush’ started (6), and indeed the ‘picks and shovels’ of this field represent a rapidly maturing sector. We shouldn’t be surprised by this: Making complex and expensive but effective medicines inevitably requires a sophisticated infrastructure and supply chain. Fundamentally, this is good news, indicating capital inflow that will be motivated by driving down CoG.”

References

1 Gottlieb S. Statement on New Policies to Advance Development of Safe and Effective Cell and Gene Therapies. US Food and Drug Administration: Rockville, MD, January 2019; https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/statement-fda-commissioner-scott-gottlieb-md-and-peter-marks-md-phd-director-center-biologics.

2 Approved Cellular and Gene Therapy Products. US Food and Drug Administration: Rockville, MD, 29 March 2019; https://www.fda.gov/vaccines-blood-biologics/cellular-gene-therapy-products/approved-cellular-and-gene-therapy-products.

3 Stanton D. Top 10 Advanced Therapy Milestones of 2019: Patient Access Takes Center Stage. BioProcess Insider 27 January 2019; https://bioprocessintl.com/bioprocess-insider/global-markets/top-10-advanced-therapy-milestones-of-2019-patient-access-takes-center-stage.

4 Terry M. UC-Berkeley Rekindles U.S. Patent Dispute with the Broad Institute Over CRISPR. BioSpace 1 August 2019; https://www.biospace.com/article/crispr-patent-battle-isn-t-quite-over-yet.

5 Stanton D. The Technology of Tomorrow — Today. BioProcess Int. 18(4) 2020: S15–S19; https://bioprocessintl.com/manufacturing/cell-therapies/cell-and-gene-therapy-manufacturing-technology-of-tomorrow-today.

6 Spink K. 2019: The Year the Tools and Tech C and GT Gold Rush Began. Straight from the Horse’s Mouth 31 December 2019; https://darkhorseconsultinggroup.com/2019-the-year-the-tools-tech-cgt-gold-rush-began.

Cheryl Scott is cofounder and senior technical editor of BioProcess International, PO Box 70, Dexter, OR 97431; 1-646-957-8879; [email protected]. Dan Stanton is founding editor of BioProcess Insider.

The first half of this article is adapted from an original online BioProcess Insider report on 22 January 2020; https://bioprocessintl.com/bioprocess-insider/regulations/phacilitate-2020-fda-commercial-cell-and-gene-therapy-forecast-unlikely.

You May Also Like