Seal Intrusion — A Hidden CostSeal Intrusion — A Hidden Cost

The following is an extract from a paper presented at the Orlando ISPE Annual Meeting on November 2010 by Dr. John Toynbee.

Seal or gasket material protruding into the process flow within pipework carries a number of production issues, many of which have serious cost implications.

Areas of seal intrusion or recess are caused by oversized or undertightened gaskets that create a trap at the clamp union. This creates a number of production problems:

System drainage and cleaning are compromised

Excess product is held in the system — creating a microbial trap

Intrusion into the process stream creates damming and exposes the gasket to excessive shear

Seal failure is accelerated because increased contact area is subjected to aggressive CIP chemicals

Risk of process contamination increases due to shearing of seal particulates.

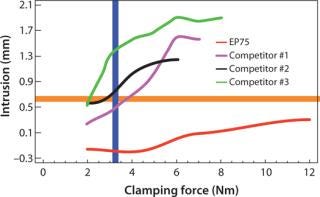

The following chart, compiled from James Walker test data on 1-inch clamp gaskets, demonstrates rates of seal intrusion plotted against clamping force for James Walker Elast-O-Pure EP75 and the three closest competitor materials.

The traces clearly show that only Elast-O-Pure meets ASME Category 2 (± 0.2 mm) for intrusion performance on installation at the ASME recommended clamping force of 3.3 Nm/30 in.lb.

Figure 1: ()

As the clamp is tightened, three of the materials soon reach intrusion levels in excess of a millimeter, while Elast-O-Pure remains within Category 1 performance specification (± 0.6 mm) even at four times the recommended clamping force. Performance Impact

The performance of a seal material is totally dependent on selection of the specific type and grade of all ingredients as well as the compounding and moulding process. As a direct result of saving perhaps tens of dollars on the cost of a seal, thousands of dollars can be incurred in increased maintenance or unscheduled downtime, and millions of dollars risked on product contamination.

The constant drive to reduce unit costs for elastomeric seals has resulted in their becoming a commodity. Many manufacturers — to meet the low prices demanded — are buying “off the shelf” compounds, which are selected for their ease of manufacturing rather than operational performance. As a result, while pricing points may be achieved, operational capability is often severely compromised.

Seals may well be of a material that is USP Class VI certified, but this is only an indication of biocompatibility and by no means an indication of how the material concerned will function as a seal. Neither does it guarantee the origins and traceability of the elements that go to make up the final compound or provide any certification of the suitability of the production methods that would be involved in making a seal from the compound.

So what’s the answer? On a production unit, once a seal is in place and the clamp tightened, how do you know what is happening inside?

There are three elements to ensuring minimization of intrusion problems:

Make sure you specify high performance elastomeric seals offering proven intrusion resistance

Ensure that clamp joints are not over-tightened

Carefully examine joints during change-out and revisit the first two points. Take up the issue with your seal supplier if any signs of excessive seal intrusion or recession are discovered.

About the Author

Author Details

Dr John Toynbee is a senior development technologist at James Walker & Co Ltd. For more information contact David Donnelly, pharmaceutical industry manager; +44-1270-536000; [email protected]; www.jameswalker.biz.

You May Also Like