Therapeutic IgG-Like Bispecific Antibodies: Modular Versatility and Manufacturing Challenges, Part 2Therapeutic IgG-Like Bispecific Antibodies: Modular Versatility and Manufacturing Challenges, Part 2

HTTP://STOCK.ADOBE.COM

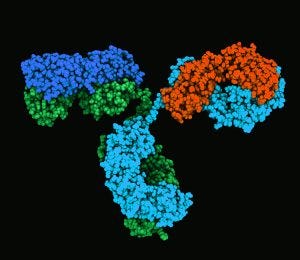

Monoclonal antibodies (MAbs) are bivalent and monospecific, with two antigen-binding arms that both recognize the same epitope. Bispecific and multispecific antibodies, collectively referred to herein as bispecific antibodies (bsAbs), can have two or more antigen-binding sites, which are capable of recognizing and binding two or more unique epitopes. Based on their structure, bsAbs can be divided into two broad subgroups: IgG-like bsAbs and non–IgG-like bsAbs. We have chosen to focus on the former in this review. Part one provides a pipeline update for IgG-like bsAbs; lists their general advantages and disadvantages compared with MAbs; and describes different formats, their structural characteristics, and how structural variations contribute to improved productivity (1). Here, part 2 goes into more detail describing how bsAbs are applied in medical research as well as basic upstream and downstream manufacturing considerations.

Comparing bsAbs and Monoclonal Antibodies

Like MAbs, IgG-like bsAbs can be used to deliver toxins, drugs, or radiolabeled compounds to inactivate ligands, to antagonize receptors, and to mediate antibody dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity (ADCC) or complement-mediated cytotoxicity (CMC). However, the dual specificity of bsAbs creates additional therapeutic options for treating diseases that do not respond sufficiently to monospecific MAbs. The box below lists functionalities of IgG-like bispecific antibodies.

Functions of IgG-Like bsAbs |

|---|

Bind ligands and inhibit ligand–receptor interaction. |

Bind cell-surface receptors and inhibit ligand binding. |

Bind a virulence factor and inhibit endocytosis or escape from endosome. |

Bind a cell surface receptor and activate or inactivate it. |

Crosslink cell-surface receptors to induce or inhibit intracellular signal transduction. |

Bind a cell-surface antigen and induce antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity (ADCC) or complement-mediated cytotoxicity (CMC) through Fc-domain interaction with effector cells and/or molecules. |

Bind immune-cell–activating surface (co)receptor and retarget it to cell-type expressing a specific surface antigen. |

Deliver a covalently bound payload (e.g., cytotoxins, cytokines, enzymes, or drug-filled micelles/nanoparticles) to target cells. |

Bispecifics can target similarly localized cell surface proteins and functionally crosslink them. Chugai Pharmaceutical’s ACE910, an IgG-like bsAb that has completed clinical phase 1–2, was developed for treatment of hemophilia A. It has been shown to crosslink activated factor IX and factor X in vitro, thus mimicking the cofactor activity of factor VIII. Binding of the first antigen by a dual-armed IgG-like bsAb can increase the rate of the second antigen-binding event in a phenomenon known as cross-arm binding efficiency (2, 3).

Many bsAbs are designed to “redirect” immune cells. This subset of bsAbs simultaneously binds an immune cell target-activating complex and a cancer cell surface antigen. For example, Fresenius Biotech/Trion Pharma’s catumaxomab (anti-EpCAM × anti-CD3) targets tumor cells expressing human epithelial cell adhesion molecule (EpCAM) and CD3+ T-effector cells (4). Many bsAbs use CD3 as a target for effector T-cell recruitment and activation, NKp46 or CD16 for NK cells (5), and CD64 for monocytes/macrophages (6). Activating isolated T-cells and NK cells before infusion with bsAbs can further increase target cell cytotoxicity (7).

T-cell activation through CD3-binding can lead to anergy if costimulatory pathways are not also activated. That problem has been circumvented by engineering T-cells to express a chimeric receptor target that activates them independent of the major histocompatibilty complex (MHC).

Note that a potential safety risk in activating immune-effectors with MAbs is the release of proinflammatory cytokines — and bsAbs are not exempt from this phenomenon. The response has been observed in several bsAb clinical trials: e.g., for ertumaxomab (intravenous administration of anti-HER2 × anti-CD3 rat–mouse hybrid bsAb) (8), catumaxomab (intraperitoneal administration of anti-EpCAM × anti-CD3 rat–mouse hybrid bsAb) (9), and blinatomomab (intravenous administration of anti-CD19 × anti-CD3 non–IgG-like bsAb, a T-cell engager) (10). Administration of fever reducers, antihistamines, or corticosteroids can mitigate this response, as can incremental increase in dosage (11, 12).

Administration of a bsAb designed to target a cancer-specific epitope and a peptide such as histamine-succinyl-glycine (HSG) hapten–peptide can be used to increase the total delivered dose of radioimmunotherapeutics while reducing off-target effects (13–16). Patients first are infused with these specially designed bsAbs to bind the cancer epitope. After a short delay for clearance of unbound excess bsAb, the patients then are infused with a radiolabeled HSG peptide. This can be used for molecular-imaging purposes or, depending on its number of HSG-binding domains, a bsAb can deliver a higher radiation dose to a tumor than can a directly labeled monoclonal Ab. Off-target damage is reduced significantly because nonbound radiolabeled peptide is cleared rapidly by a patient’s kidneys.

Bispecifics also can block multiple surface virulence factors present on infectious agents or their targets. For example, a dual variable domain (DVD)-bsAb currently being tested for treatment of dengue fever binds and blocks two surface epitopes involved in host-cell binding and endosomal translocation of the virus (17). With a similar mechanism, a different DVD-IgG bsAb slows the progression of Ebola by binding a glycoprotein on the viral surface. Upon entering an endosome, the bound bsAb also blocks viral interaction with NPC1 endosomal host-cell receptors, inhibiting release of viruses into the cell’s cytosol (18).

Some bsAbs have been designed to translocate across the blood–brain barrier (BBB). Although the BBB can block penetration by even the smallest Fv and Fab fragments, researchers at Genentech have developed a knob-in-hole (KiH)–based IgG-like bsAb that binds with low affinity to the transferrin receptor, allowing it to be transported across the barrier. The low affinity allows it to dissociate and bind a second target such as β-secretase 1, which is part of the metabolic pathway that produces amyloid proteins in human brains (19–20). With the exception of lipid-soluble small molecules or those capable of carrier-mediated transport, achieving similar concentrations of therapeutics in the brain previously has required complex or invasive techniques such as osmotic BBB modification or direct infusion into cerebrospinal fluid (21–23).

In addition to all those varied functions, bsAbs also can reduce development of resistance caused by upregulation of alternative signaling pathways. Bispecifics require no additional clinical testing to determine compatibility with additional MAbs if multispecific treatment is necessary. The design flexibility of bsAbs opens up new therapeutic options that have been impossible with MAbs.

IgG-Like bsAbs Manufacturing: Upstream

Producing structurally complex molecules at commercial scale always is difficult. As with MAbs, however, many pitfalls associated with IgG-like bsAb production can be prevented through careful consideration during the design phase.

Design Considerations: We have shown that bsAb design formats can vary widely. However, the practical requirements of production scale-up create constraints in manufacturing some of these formats. In general, the more complex the molecular design, the less practical it will be for commercial production. Many of the IgG-like bsAb formats are designed to facilitate manufacturing and reduce the amount of mispaired molecules produced. During the product design phase, research teams must consult with their development colleagues to determine whether equipment required to produce their bsAb will be available at commercial scale — and whether the process can be performed at reasonable cost. Even the most promising therapeutic may not reach market if it cannot be manufactured.

Also, if a contract manufacturing organization (CMO) is to be a partner for clinical production, it will be important for the product sponsor to design (at bench scale) a process that will be easy to implement and transfer. A complex or esoteric process makes technology transfer difficult, and few CMOs will be competent to execute such a process. Demonstrated experience with bsAbs should be a major criterion for choosing a specific partner for outsourcing.

Selection of Cell Lines: The choice of cell line to use for IgG-like bsAb production depends on each product’s unique physical characteristics. Commercial MAb production primarily begins with stably transfected mammalian cell lines such as Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells or the NS0 and Sp2/0 murine lymphoid lines. Those cell lines can produce and secrete proteins with similar glycosylation to naturally occurring human immunoglobulins (24).

The CHO line is the current workhorse of the therapeutic MAb industry, producing most MAbs that are currently on the market. Using state-of-the-art methods, CHO cells grown under appropriate culture conditions can express antibodies at >5 g/L. These cells have been used to produce Genentech’s CrossMAb bsAbs (25). In recent years, NS0 and Sp2/0 cell lines have been chosen less frequently than CHO because of potential product safety concerns: Both murine lines integrate glycans with higher immunogenic potential into proteins than do CHO cell lines (24, 26–28).

Human-derived cell lines also are available for protein-based therapeutic production. Such cells do not incorporate immunogenic glycosylation structures; however, a major safety concern is susceptibility to adventitious and endogenous viruses. HEK293 and Cevec Pharmaceuticals’s CAP-T cells are two human lines that have been used early in bsAb development — e.g., of CrossMAb (Creative Biolabs), DuetMab (29, 30), and dual-action Fab (DAF) (31) formats — but they are best suited for transient expression. The Per. C6 cell line could offer improved utility for commercial bsAb production; however, it is proprietary to Janssen Pharmaceuticals and is no longer accessible for general use (32, 33).

Microbial cells such as Pichia pastoris (34, 35) and Escherichia coli have been used to generate Ab fragments, half-Abs, non–IgG-like bsAbs, and MAbs and can be used to create IgG-like bsAbs that lack glycosylation. E. coli is used mainly in production of non–IgG-like bsAbs or IgG-like bsAbs used for epitope neutralization (for which effector functions are not required). E. coli can produce aglycosylated IgG heavy chains and light chains identical to the glycosylated forms in antigen-binding affinity, stability, pharmacokinetics, and biodistribution. But production in microbial cells can be hampered by their lack of protein-folding chaperones, making protein aggregation with sequestration of product in inclusion bodies a common issue (36–38). Spiess et al. generated human IgG1-based KiH bsAbs by producing half-Abs in two separate E. coli cultures, then purifying and combining them subject to the appropriate redox conditions to assemble the final bsAbs (39).

Cell-free expression systems based on purified E. coli cellular components also have been used to produce aglycosylated MAbs. Such systems avoid some complications otherwise associated with whole-cell E. coli–based production — e.g., sequestration of product in inclusion bodies and production of endotoxin (40, 41). It may be possible to incorporate glycosylation pathway enzymes into cell-free translation systems to produce glycoproteins, but doing so has yet to be assessed (42).

Production Bioreactor and Harvest: Despite best molecular design efforts to promote correct chain pairing, side products are still produced: e.g., covalent and noncovalent aggregates, mispaired product, partial product, and other variants. Because they can affect final-product efficacy and safety, those side products should be removed. Certain approaches during vector design, cell-line development, and cell culture production phases can limit the presence of side products and significantly reduce their burden on downstream processing.

With bsAbs, it is advisable to express heavy chains (HC) and light chains (LC) on separate plasmids because optimizing the plasmid ratio during transfection can be the single most important factor to promote proper assembly of desired products. Other upstream factors that can influence product quality are bioreactor type and culture mode (e.g., perfusion or fed-batch), culture duration, supply of metabolic precursors, accumulation of metabolic waste products, concentration of gases, and culture temperature. Developers can monitor the formation of aggregates, noncovalent misformed and partial products, and fragments using size-exclusion high-performance liquid chromatography (SE-HPLC).

Monitoring to Understand the Process: Many of the IgG-like bsAbs have complex oligomeric structures and are prone to misassembly. So it is important to ensure that aggregation and misformed products be identified and monitored throughout the production process. Haberger et al. developed a method to identify size variants accurately during CrossMAb production. After first identifying the fragment and aggregate variations present in their samples using native electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (ESI-MS), the investigators coupled a size-exclusion–based ultrahigh-pressure liquid chromatography (SEC-UPLC) with UV detection method to the native ESI-MS for monitoring alternate size variants during upstream and downstream processing (44). That methodology can be applied at both early and later process stages for other complex bsAbs.

Optimization of Culture Conditions: As with MAbs, cultured cells producing high quantities of bsAbs will have changing metabolic needs during culture. Assessing their metabolism by measuring consumption of media components over the culture duration is an excellent way to guide timing and composition of feeds. In CHO cell cultures, for example, amino acids such as cysteine and serine can become rate limiting for production of glutathione (44). Medium additives with limited stability can be replaced with more stable precursors such as N-acetyl-l-cysteine or S-sulfo-l-cysteine for cysteine (45) and alanyl-l-glutamine or glycyl-l-glutamine for glutamine. Lipoic acid can become rate limiting for vitamin C (ascorbate) and E (tocopherol) cycling. One or a combination of those could be added as supplements to reduce cell stress in production.

Medium composition also can influence product quality. Purdie et al. from Eli Lilly identified medium components — cysteine and ferric ammonium citrate — as contributors to aggregate formation in their culture system, prompting the team to refine their use of a chemically defined medium and supplements (46). Luo et al. from Genentech found that metal ions of copper and zinc in the medium can increase variability in C-terminal lysine through effects on CHO intracellular carboxypeptidase activity (47). Monitoring those medium components and elements during development could help in controlling partial product, aggregate, or product variant levels in harvested material.

Culture Duration: Stability of a bsAb product in culture can vary and will affect the type of cell culture process to be used. If a bsAb (or product intermediate) is not stable for the basic 14-day fed-batch culture, then switching from fed-batch to a perfusion mode may be necessary. Perfusion culture systems regularly remove product with spent media, limiting exposure to cell waste products that accelerate degradation. That way, bsAbs are harvested and purified more quickly, which is helpful for unstable products.

bsAbs Manufacturing: Downstream

The platform downstream processes commonly used for MAbs today depends on three biophysical characteristics: Fc-enabled capture using a protein A affinity chromatography column, stability at low pH (for protein A column elution and viral inactivation), and a basic pI (>7) to enable efficient removal of impurities (including host cell proteins, DNA, and endotoxin) using ion-exchange chromatography (IEC). In IgG-like bsAbs, those three characteristics generally are retained. However, product-related impurities are a more significant issue, and downstream operations may be less consistent in separating bsAbs from partial products and mispaired species.

Product Capture: The primary method of capture for Fc-containing MAbs and bsAbs (with the exception of IgG3) is protein A affinity chromatography. The high specificity and affinity at neutral pH of protein A for residues in the Fc domain can be used to isolate these products directly from clarified harvest, removing most host-cell proteins (HCPs) and residual DNA. In high-density cultures, HCPs may bind nonspecifically to product or resin, but a wash step after binding (or pretreatment of clarified harvest) can eliminate that problem.

Altered Protein A Binding Affinity: In Part 1, we discussed bsAb formats that used protein engineering methods such as protein A binding ablation in one of two HCs to shift the elution pH of a correctly paired product for improved capture selectivity, reducing the burden on subsequent polishing steps. Rat/mouse hybrid bsAbs such as catumaxomab use innate differences in protein A binding of rat and mouse HCs: Rat-derived Fc domains cannot bind to it, whereas mouse-derived HCs have a strong affinity for protein A. So the rat parental Ab is not retained by a protein A column, the rat/mouse bsAb can be eluted from it at a pH of ~5.8, and the mouse parental elutes at a pH of ~3.0 (4, 48).

Modifications to protein A binding also can be engineered into one of the two HC CH3 domains, as shown by Tustian et al (49). These investigators exploited a histidine residue in the CH3 domain of IgG1 that is critical for protein A binding. Replacing that residue at position 435 with arginine in one of the two heavy chains (H435R) alters the elution pH of HC heterodimers in relation to that of homodimers (49). The arginine residue at position 435 occurs in the IgG3 subclass that cannot bind to protein A, making this amino acid replacement nonimmunogenic.

High-Capacity Cation-Exchange Chromatography: High-capacity cation-exchange chromatography (HC-CEX) can be a cost-effective alternative for capture of bsAbs that cannot tolerate the acidic elution conditions required for protein A affinity–based capture. CEX is most often used as a polishing step because of its conductivity limitations; however, increased salt tolerance and binding capacity in newly developed CEX resins make this method a viable alternative for capture of both MAbs and bsAbs.

CEX has been tested as a capture method for MAbs with a pI range of 6.5–8.7, and product yield was high (dynamic binding capacities of >100 grams of protein per liter of resin) depending on the resin used and the characteristics of the MAb. Both Capto S (GE Healthcare) and Toyopearl GigaCap S-650M (Tosoh Bioscience) resins have been tested as capture methods for MAbs, and both can be scaled-up. However, as noted above, HCP clearance efficiency in CEX depends on the productt’s pI (50–52).

Figure 1: Quantitation of mispaired light chains — even with engineered modifications to direct correct chain pairings, mispaired light chains are difficult to eliminate entirely. Quantifying their abundance in a mixture can be difficult, especially for isobars (mispaired products of molecular weight identical to that of the desired product). Here, the desired product is H1L1/H2L2 (red box). Lysyl-C digestion releases Fab fragments from all assembled forms, which then can be isolated and analyzed. With relative quantities of mispaired nonisobars (H1L1/H2L1 and H1L2/H2L2) measured using LC/MS, the isobar percentage (H1L2/H2L1) can be calculated. Thus, components of the Fab mixture can be used to calculate the abundance of correct LC-paired product.

Additional Capture Steps for Product Selection: Kappa (κ) and lambda (λ) light-chain bsAbs require three sequential affinity chromatography methods in their downstream processes to select for the correct HC–LC pairing. Starting with a protein A affinity method to capture HC-containing structures, sequential κ and λ affinity chromatography steps then select for structures containing those light chains. These combined affinity methods are efficient in removing most mispairs; they cannot remove product isobars (Figure 1: H1L2/ H2L1).

Low pH Instability — Effect on Protein A Elution and Low pH Hold for Viral Inactivation: Bispecifics are prone to aggregation. Three major factors contributing to protein aggregation are salting out, isoelectric precipitation, and acid sensitivity. Some bsAbs may not withstand the low pH required for protein A capture and viral inactivation.

For those that are sensitive to the protein A elution condition, a change of elution buffer (to citrate, acetate, or succinate) could improve product stability, as might adding a stabilizing excipient such as arginine (0.5–2 M), NaCl (>1 M), or glycerol (20%) to the elution buffer (53). Keep in mind that such modified elution conditions may affect viral inactivation.

Alternatives to low pH hold are available for viral inactivation. Solvent detergent treatment using 0.15% tri-N-butyl phosphate (TnBP)/0.5% Triton X-100 has been demonstrated as effective against a range of enveloped viruses, even at 4 °C (54). The fatty acid caprylate also can be effective for virus inactivation (55).

Product Polishing: Protein A and CEX capture methods are effective for reducing nonproduct (process-related) impurities, but product-related impurities (e.g., mispaired products, fragments, and aggregates) contained in postcapture bsAb mixtures must be removed by polishing steps. Such operations should be tailored to each bsAb and the specific product-related impurities that will be present with it. Many bench-scale processes involve SEC, but this mode of chromatography is difficult to scale and cannot remove mispaired products.

The most difficult type of mispaired product to remove is an “isobar”— a molecule with the same mass as correctly paired products but including mispaired LCs. Isobars can be minimized by producing half Abs in separate cell lines, then combining them under the appropriate redox conditions. But in bsAbs produced in a single host-cell line, lysyl endopeptidase digestion combined with LC-MS can be used to identify and quantify LC mispairs (Figure 1), including product isobars (56). Although they are of similar mass as that of the desired product, isobars may have subtle physicochemical differences that can be exploited using cation-exchange (CEX), anion-exchange (AEC), or hydrophobic interaction chromatography (HIC). Liu et al. detail how to use these tools for MAb purification (56).

Variation and Versatility

Bispecific antibodies represent an exciting new drug class that is expanding the clinical use of MAbs. Advancements in genetic engineering and mastery of large-scale MAb production have given this field a secure foundation on which to build for the future. The ability to bind two or more unique epitopes gives bsAbs greater versatility than MAbs in their ability to

target multiple pathways

block multiple virulence factors

crosslink cell surface receptors

pretarget oncological epitope-containing cell types

deliver payloads with reduced off-target damage • redirect FcR and non-FcR expressing immune cells to kill target cells.

Although bsAb manufacturing can be complex because of the range and variety of product-related impurities that can be present, the impact of those complications can be minimized if such issues are considered early in development.

Acknowledgment

We are grateful to Laura Shih for her contribution in preparation of the figures presented in this review.

References

1 Bratt J, et al. Therapeutic IgG-Like Bispecific Antibodies and Their Manufacturing Challenges, Part 1. BioProcess Int. 15(11) 2017: 38–45.

2 Fitzgerald J, Lugovskoy A. Rational Engineering of Antibody Therapeutics Targeting Multiple Oncogene Pathways. MAbs 3(3) 2011: 299–309; doi:10.4161/mabs.3.3.15299.

3 Harms BD, et al. Understanding the Role of Cross-Arm Binding Efficiency in the Activity of Monoclonal and Multispecific Therapeutic Antibodies. Methods 65(1) 2014: 95–104; doi:10.1016/j.ymeth.2013.07.017.

4 Linke R, Klein A, Seimetz D. Catumaxomab: Clinical Development and Future Directions. MAbs 2(2) 2010: 129–136.

5 Bispecific Antibodies Technology: NK Cells Engagers. Innate Pharma: Marseille, France, 2017; www.innate-pharma.com/en/pipeline/bispecific-antibodies-technology-nk-cells-engagers.

6 Curnow RT. Clinical Experience with CD64-Directed Immunotherapy. An Overview. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 45(3–4) 1997: 210–215.

7 Gleason MK, et al. Bispecific and Trispecific Killer Cell Engagers Directly Activate Human NK Cells through CD16 Signaling and Induce Cytotoxicity and Cytokine Production. Mol. Cancer. Ther. 11(12) 2012: 2674–2684; doi:10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-12-0692.

8 Kiewe P, et al. Phase 1 Trial of the Trifunctional Anti-HER2 X Anti-CD3 Antibody Ertumaxomab in Metastatic Breast Cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 12(10) 2006: 3085–3091.

9 Heiss MM, et al. Immunotherapy of Malignant Ascites with Trifunctional Antibodies. Int. J. Cancer. 117(3) 2005: 435–443; doi:10.1002/ijc.21165.

10 Klinger M, et al. Immunopharmacologic Response of Patients with B-Lineage Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia to Continuous Infusion of T Cell–Engaging CD19/CD3-Bispecific Bite Antibody Blinatumomab. Blood 119(26) 2012: 6226–6233; doi:10.1182/blood-2012-01-400515.

11 Kroschinsky F, et al. Intensive Care in Hematological and Oncological Patients (iCHOP) Collaborative Group. New Drugs, New Toxicities: Severe Side Effects of Modern Targeted and Immunotherapy of Cancer and Their Management. Crit. Care 21(1) 2017: 89–99; doi:10.1186/s13054-017-1678-1.

12 Topp MS, et al. Safety and Activity of Blinatumomab for Adult Patients with Relapsed or Refractory B-Precursor Acute Lymphoblastic Leukaemia: A Multicentre, Single-Arm, Phase 2 Study. Lancet Oncol. 16(1) 2015: 57–66; doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(14)71170-2.

13 Bodet-Milin C, et al. Immuno-PET Using Anticarcinoembryonic Antigen Bispecific Antibody and 68Ga-Labeled Peptide in Metastatic Medullary Thyroid Carcinoma: Clinical Optimization of the Pretargeting Parameters in a First-in-Human Trial. J. Nucl. Med. 57(10) 2016: 1505–1511; doi:10.2967/jnumed.116.172221.

14 Sharkey RM, et al. Metastatic Human Colonic Carcinoma: Molecular Imaging with Pretargeted SPECT and PET in a Mouse Model. Radiology 246(2) 2008: 497–507; doi:10.1148/radiol.2462070229.

15 Clinical Trials: ImmunoTEP with 68-Ga in Metastatic Colorectal Cancer (NCT02587247); ImmunoTEP for Patients with Medullary Thyroid Carcinoma (NCT01730638); ImmunoTEP AU 68-Ga-IMP-288 for Patients with a Recurrence of HER2 Negative Breast Carcinoma Expressing CEA (NCT01730612); TF-2-Small Cell Lung Cancer Radio Immunotherapy (NCT01221675). US National Library of Medicine database: www.clinicaltrials.gov.

16 Schoffelen R, et al. Pretargeted ImmunoPET Imaging of CEA-expressing Tumors with a Bispecific Antibody and a 68Ga- and 18F-labeled Hapten-peptide in Mice with Human Tumor Xenografts. Mol. Cancer Ther. 9(4) 2010: 1019–1027; doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-09-0862.

17 Shi X, et al. A Bispecific Antibody Effectively Neutralizes All Four Serotypes of Dengue Virus by Simultaneous Blocking Virus Attachment and Fusion. MAbs 8(3) 2016: 574–584; doi:10.1080/19420862.2016.1148850.

18 Wec AZ, et al. A “Trojan Horse” Bispecific-Antibody Strategy for Broad Protection against Ebola Viruses. Science 354(6310) 2016: 350–354; doi:10.1126/science.aag3267.

19 Yu YJ, et al. Therapeutic Bispecific Antibodies Cross the Blood-Brain Barrier in Nonhuman Primates. Sci. Transl. Med. 6(261) 2014: 261ra154; doi:10.1126/scitranslmed.3009835.

20 Pardridge WM. Re-engineering Therapeutic Antibodies for Alzheimer’s Disease As Blood–Brain Barrier Penetrating Bi-Specific Antibodies. Expert Opin. Biol. Ther. 6(12) 2016: 1455–1468; doi:10.1080/14712598.2016.1230195.

21 Couch JA, et al. Addressing Safety Liabilities of TfR Bispecific Antibodies That Cross the Blood–Brain Barrier. Sci. Transl. Med. 5(183) 2013: 183ra57, 1–12; doi:10.1126/scitranslmed.3005338.

22 Pardridge WM. Transport of Small Molecules Through the Blood–Brain Barrier: Biology and Methodology. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 15(1–3) 1995: 5–36.

23 Neuwelt EA, et al. Osmotic BloodBrain Barrier Modification: Monoclonal Antibody, Albumin, and Methotrexate Delivery to Cerebrospinal Fluid and Brain. Neurosurgery 17(3) 1985: 419–423.

24 Durocher Y, Butler M. Expression Systems for Therapeutic Glycoprotein Production. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 20(6) 2009: 700–707; doi:10.1016/j.copbio.2009.10.008.

25 Schaefer W, et al. Immunoglobulin Domain Crossover As a Generic Approach for the Production of Bispecific IgG Antibodies. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 108(27) 2011: 11187–11192.

26 Dumont J, et al. Human Cell Lines for Biopharmaceutical Manufacturing: History, Status, and Future Perspectives. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 36(6) 2016: 1110–1122; doi:10.3109/07388551.2015.1084266.

27 Ghaderi D, et al. Implications of the Presence of N-Glycolylneuraminic Acid in Recombinant Therapeutic Glycoproteins. Nat. Biotechnol. 28(8) 2010: 863–867; doi:10.1038/nbt.1651.

28 Li F, et al. Cell Culture Processes for Monoclonal Antibody Production. MAbs 2(5) 2010: 466–477; doi:10.4161/mabs.2.5.12720.

29 Mazor Y, et al. Insights into the Molecular Basis of a Bispecific Antibody’s Target Selectivity. MAbs 7(3) 2015: 461–469; doi:10.1080/19420862.2015.1022695.

30 Mazor Y, et al. Improving Target Cell Specificity Using a Novel Monovalent Bispecific IgG Design. MAbs 7(2) 2015:377–389; doi:10.1080/19420862.2015.1007816.

31 Lee CV, et al. High-Affinity Human Antibodies from Phage-Displayed Synthetic Fab Libraries with a Single Framework Scaffold. J. Mol. Biol. 340(5) 2004: 1073–1093; doi:10.1016/j.jmb.2004.05.051.

32 Jones D, et al. A High-Level Expression of Recombinant IgG in the Human Cell Line PER.C6. Biotechnol. Prog. 19(1) 2003: 163–168; doi:10.1021/bp025574h.

33 Kuczewski M, et al. A Single-Use Purification Process for the Production of a Monoclonal Antibody Produced in a PER.C6 Human Cell Line. Biotechnol. J. 6(1) 2011: 56–65; doi:10.1002/biot.201000292.

34 Hamilton SR, Gerngross TU. Glycosylation Engineering in Yeast: The Advent of Fully Humanized Yeast. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 18(5) 2007: 387–392; doi:10.1016/j.copbio.2007.09.001.

35 Li H, et al. Optimization of Humanized IgGs in Glycoengineered Pichia pastoris. Nat. Biotechnol. 24(2) 2006: 210–215; doi:10.1038/nbt1178.

36 Ju MS, Jung ST. Aglycosylated FullLength IgG Antibodies: Steps Toward NextGeneration Immunotherapeutics. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 30, 2014: 128–139; doi:10.1016/j.copbio.2014.06.013.

37 Chan CE, et al. Optimized Expression of Full-Length IgG1 Antibody in a Common

E. coli Strain. PLoS One 5(4) 2010: e10261; doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0010261.

38 Graumann K, Premstaller A. Manufacturing of Recombinant Therapeutic Proteins in Microbial Systems. Biotechnol. J. 1(2) 2006: 164–186; doi:10.1002/biot.200500051.

39 Spiess C, et al. Development of a Human IgG4 Bispecific Antibody for Dual Targeting of Interleukin-4 (IL-4) and Interleukin-13 (IL-13) Cytokines. J. Biol. Chem. 288(37) 2013: 26583–26593; doi:10.1074/jbc.M113.480483.

40 Xu Y, et al. Production of Bispecific Antibodies in “Knobs-into-Holes” Using a Cell-Free Expression System. MAbs 7(1) 2015: 231–242; doi:10.4161/19420862.2015.989013.

41 Goerke AR, Swartz JR. Development of Cell-Free Protein Synthesis Platforms for Disulfide Bonded Proteins. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 99(2) 2008: 351–367; doi:10.1002/bit.21567.

42 Guarino C, DeLisa MP. A ProkaryoteBased Cell-Free Translation System That Efficiently Synthesizes Glycoproteins. Glycobiology 22(5) 2012: 596–601; doi:10.1093/glycob/cwr151.

43 Haberger M, et al. Rapid Characterization of Biotherapeutic Proteins By Size-Exclusion Chromatography Coupled to Native Mass Spectrometry. MAbs 8(2) 2016: 331–339; doi:10.1080/19420862.2015.1122150.

44 Lu SC. Glutathione Synthesis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1830(5) 2013: 3143–3153; doi:10.1016/j.bbagen.2012.09.008.

45 Hecklau C, et al. S-Sulfocysteine Simplifies Fed-Batch Processes and Increases the CHO Specific Productivity via AntiOxidant Activity. J. Biotechnol. 20(218) 2006: 53–63; doi:10.1016/j.jbiotec.2015.11.022.

46 Purdie JL, et al. Cell Culture Media Impact on Drug Product Solution Stability. Biotechnol. Prog. 32(4) 2016: 998–1008; doi:10.1002/btpr.2289.

47 Luo J, et al. Probing of C-Terminal Lysine Variation in a Recombinant Monoclonal Antibody Production Using Chinese Hamster Ovary Cells with Chemically Defined Media. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 109(9) 2012: 2306–2315; doi:10.1002/bit.24510.

48 Lindhofer H, et al. Preferential SpeciesRestricted Heavy/Light Chain Pairing in Rat/Mouse Quadromas: Implications for a Single-Step Purification of Bispecific Antibodies. J. Immunol. 155(1) 1995: 219–225.

49 Tustian AD, et al. Development of Purification Processes for Fully Human Bispecific Antibodies Based Upon Modification of Protein A Binding Avidity. MAbs 8(4) 2016: 828–838; doi:10.1080/19420862.2016.1160192.

50 Tao Y, et al. Evaluation of High-Capacity Cation-Exchange Chromatography for Direct Capture of Monoclonal Antibodies from High-Titer Cell Culture Processes. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 111(7) 2014: 1354–1364.

51 Miesegaes GR, et al. Monoclonal Antibody Capture and Viral Clearance By Cation Exchange Chromatography. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 109(8) 2012: 2048–2058; doi:10.1002/bit.24480.

52 Lain B, et al. Development of a High-Capacity MAb Capture Step Based on Cation-Exchange Chromatography. BioProcess Int. 7(5) 2009: 26–34.

53 Arakawa T, et al. Elution of Antibodies from a Protein A Column by Aqueous Arginine Solutions. Protein Expr. Purif. 36(2) 2004: 244–248; doi:10.1016/j.pep.2004.04.009.

54 Roberts PL. Virus Inactivation By Solvent/Detergent Treatment Using Triton X-100 in a High Purity Factor VIII. Biologicals 36(5) 2008: 330–335; doi:10.1016/j.biologicals.2008.06.002.

55 Korneyeva M, et al. Enveloped Virus Inactivation By Caprylate: A Robust Alternative to Solvent-Detergent Treatment in Plasma Derived Intermediates. Biologicals 30(2) 2002: 153–162; doi:10.1006/biol.2002.0334.

56 Yin Y, et al. Precise Quantification of Mixtures of Bispecific IgG Produced in Single Host Cells by Liquid Chromatography–Orbitrap High-Resolution Mass Spectrometry. MAbs 8(8) 2016: 1467–1476; doi:10.1080/19420862.2016.1232217.

Further Reading

Canfield SM, Morrison SL. The Binding Affinity of Human IgG for Its High Affinity Fc Receptor Is Determined by Multiple Amino Acids in the CH2 Domain and Is Modulated by the Hinge Region. J. Exp. Med. 173(6) 1991: 1483–1491.

Li T, et al. Modulating IgG Effector Function by Fc Glycan Engineering. Proc Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 114(13) 2017: 3485–3490; doi:10.1073/pnas.1702173114.

Liu HF, et al. Recovery and Purification Process Development for Monoclonal Antibody Production. MAbs 2(5) 2010: 480–499.

Jennifer Bratt and Angela Linderholm are consultants, Bryan Monroe is a senior consultant, and Steven Chamow is principal consultant at Chamow and Associates, Inc. in San Mateo, CA 94403; 1-650-345-1878; [email protected]; www.chamowassociates.com.

You May Also Like