A Multistep Research Protocol to Develop and Implement Validated Guidelines for CMO RFI and RFP Processes: Biopharmaceutical Vendor Evaluation and Selection Minimum Standards (BioVesel)A Multistep Research Protocol to Develop and Implement Validated Guidelines for CMO RFI and RFP Processes: Biopharmaceutical Vendor Evaluation and Selection Minimum Standards (BioVesel)

WWW.ISTOCKPHOTO.COM

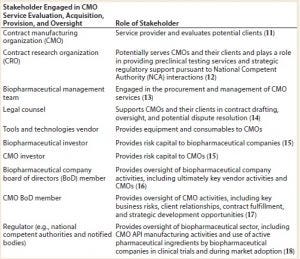

Pursuant to the proposal for validated minimum standards for biopharmaceutical contract manufacturing organization (CMO) request-for-information (RFI) and request-for-proposal (RFP) processes (biopharmaceutical vendor evaluation and selection minimum standards, BioVesel) (1), we propose herein a multistep research protocol to develop and implement the BioVesel standards. This proposal is intended as a basis for discussion among mulitple stakeholders. Detailed research protocols for each proposed stage in the development and implementation of BioVesel will be drafted and published separately. The context of the proposed research is an exercise to gather and synthesize the opinions of stakeholders involved in the evaluation, acquisition, provision, and oversight of biopharmaceutical CMO services (Table 1).

Table 1: Overview of stakeholders engaged in contract manufacturing organization (CMO) service evaluation, acquisition, provision, and oversight

Table 1 shows the many stakeholders engaged in a contract manufacturing lifecycle (evaluation, acquisition, provision, and oversight). You might be surprised by the breadth of stakeholder participation in the CMO lifecycle and reflect on your past experiences of CMO RFI/RFP processes in which a significant

number of those stakeholders may have been omitted a priori (2). In particular, the early engagement of CMO and biopharmaceutical company board of directors (BoD) members often is omitted from CMO tendering and management processes. BoD member engagement often is restricted to approval for management to enter into a master service agreement (MSA) with a CMO and in the event that something unfortunately goes wrong (3).

Proactive biotechnology corporate governance is essential at all stages of company and vendor contract lifecycles (1, 4). For example, biopharmaceutical company BoD members should be actively engaged in high-level evaluation, development, and implementation of RFP processes. That includes regular updates from management to ensure that managers have clear direction from directors and/or shareholders (5).

Such actions also will reduce the risk of BoD members — particularly those with a limited biotechnology background — of feeling “blindsided” by the process and experiencing “sticker shock” when asked by management to approve a final MSA and/or statement of work (SoW) (6). We suggest that CMOs communicate clearly with their internal executive management and BoD members as necessary to ensure clarity on resource and investment implications associated with new clients and contracts (7). Industry veterans unfortunately are hardened to stories in which CMOs enter into contracts they are subsequently unable to fulfill.

The scope of the protocol for BioVesel development is restricted to procurement of services according to the production of good laboratory practice (GLP) or good manufacturing practice (GMP) active pharmaceutical ingredient (API), which includes process development activities. Assay development, immunogenicity, external API and ancillary product testing, and standalone installation/operational/performance qualification (IQ/OQ/PQ) services are beyond the intended scope of BioVesel (8). BioVesel will apply to services in most jurisdictions and for procurement of services with a contract value that is of material risk to a tenderer (which naturally will vary by company size and development stage).

BioVesel objectives will be updated continuously based on interstakeholder feedback (9). We propose 19 potential objectives (see box, next page) for the BioVesel standard as a basis for discussion. They pertain to the BioVesel standard itself rather than to RFP processes that implement the BioVesel standard.

BioVesel Standard: Research, Development, and Implementation

Research, development, and implementation of the BioVesel standard will be driven by interstakeholders’ needs to maximize end-user utility and adoption (10). We are committed to ensuring that all aspects of the standard are grounded in robust research methods.

We propose the following key aspects and methods of a multistep research protocol to develop and implement the standard for the development and implementation of BioVesel:

Systematic review of RFI and RFP processes and standards with specific reference to healthcare

Meta-analysis and systematic review of RFI and RFP processes and standards stratifying between pharma and nonpharma

Semistructured interviews with exemplar stakeholders (Table 1) to determine potential stages and documentation in RFP processes

Delphi study of draft BioVesel RFP processes and templates

Pilot study using draft BioVesel RFP processes and templates

Meta-analysis of end-user feedback of draft BioVesel RFP processes and templates

Evaluation study deploying updated draft BioVesel RFP processes and templates

Meta-analysis of end-user feedback of updated draft BioVesel RFP processes and templates

Update and issue of V1.0 BioVesel RFP processes and templates

Implementation of processes for continuous review and revision of processes and templates

Implementation of BioVesel audit process through a recognized independent third party (e.g., notified body).

Clarity, Competition, and Completion

The BioVesel objective and concept remain crystalline: Provide a simple, adaptable, and transparent framework for CMO service procurement and delivery. However, the route to implementation is complex. In particular, we highlight the need for BioVesel to prompt and support resource requirement planning within CMOs, supported with communication with their senior management and BoD members. That is a multiparty challenge that requires a multiparty solution.

Reflecting on the methods proposed here and in discussions with potential standard codevelopers and adopters, we highlight the criticality of three “watchwords” set forth in the BioVesel context, scope, and objectives: the need for clarity, competition, and completion. This trinity encapsulates neatly the three main failure modes of current relationships between CMOs and biopharmaceutical sponsor companies. We hope that through BioVesel, these three areas can represent heuristics for success. Currently, although the biotechnology industry develops and evolves at the speed of a bullet, some of the supportive framework is moving at the pace of a mammoth. Now is the moment to catapult our efforts into the 21st century, with standards fit-for-purpose to ensure that our businesses do not go extinct.

Potential Objectives for the BioVesel Standard |

|---|

Transparency: All aspects of the standard must be transparent among all stakeholders, including processes for development, implementation, and revision of the standard. |

Integrity and Traceability: The standard shall be subject to clear and appropriate controls in regard to issue, revision, and validation. |

Enforceability: Efforts shall be made to adopt the standard incrementally on a communitywide voluntary basis. |

Adaptability: Processes and procedures shall be developed for adaption of BioVesel to accommodate short-term nuances of specific RFP processes or technologies and long-term technological and business environment changes. |

Use of Existing Best Practices: BioVesel shall seek to learn from and implement existing best practices from within and outside the biopharmaceutical space, including ISO standards and other standards set forth by professional and/or trade organizations. |

Framework for negotiation processes shall be defined to support the management of interstakeholder expectations and standardization of all aspects of the RFP process, subject to overarching legal or regulatory requirements. |

Framework for Resolution of Conflicts: Frameworks for negotiation processes shall be defined to support the management of interstakeholder expectations and standardization of all aspects of the RFP process. This will be subject to overarching legal or regulatory requirements. |

Vendor Validation/Prequalification: Vendors shall undergo a (pre)qualification process before participating in RFP processes. |

Tenderer Validation/Prequalification: Tenderers shall undergo a (pre)qualification process before participating in RFP processes. |

Clearly Define Documentation Required: Any and all mandatory documentation required during the procurement process shall be defined in advance. |

Clearly Defined Parties and Their Respective Roles: The roles and responsibilities of all parties participating in RFP processes shall be defined in advance of the process commencing and updated throughout as required. |

Transferability: Insofar as possible, BioVesel shall be applicable and transferable to the maximum range of technologies, vendors, tenderers, and jurisdictions. |

Auditable: Alignment with the standard must be auditable by first-, second-, and third-party auditors. |

Permit Comparison and Contrast of Potential Service Providers/Vendors: The standard shall propose data and tools that should be collected and applied to support comparison and contrast of potential service providers and vendors by clients. |

Permit Comparison and Contrast of Potential Clients: The standard shall propose data and tools that should be collected and applied to support comparison and contrast of potential clients by service providers/vendors. |

Encourage Competition: BioVesel shall encourage and promote competition among service providers and potential clients. |

Encourage Completion: BioVesel shall encourage and promote completion and delivery of mutual commitments among service providers and potential clients. |

Risk Identification and Management: The standard shall proactively seek to identify and manage stakeholder risks on a continuous basis. |

Minimize Risk of Effort Duplication: All efforts will be made to ensure that the development, implementation, and revision of the standard shall not impart significant additional burdens on stakeholders. In particular, it should prevent duplication of effort and processes. |

References

1 Carter A, Meinert E, Brindley D. Proposing a Systematic QbD Approach Toward Validated Guidelines for CMO RFI and RFP Processes: Biopharmaceutical Vendor Evaluation and Selection Minimum Standards (BioVesel). BioProcess Int. 16(10) 2018: 22–26.

2 Shelton LM, Minniti M. Enhancing Product Market Access: Minority Entrepreneurship, Status Leveraging, and Preferential Procurement Programs. Small Bus. Econ. 50(3) 2018: 481–498.

3 Crispeels T, Willems J, Brugman P. 2015. The Relationship Between Organizational Characteristics and Membership of a Biotechnology Industry Board-of-Directors-Network. J. Bus. Ind. Market. 30(3/4) 2015: 312–323.

4 Carter A, Meinert E, Brindley D. Biotechnology Governance 2.0: A Proposal for Minimum Standards in Biotechnology Corporate Governance. Rejuvenation Res. 24 August 2018.

5 Bjornali ES, Knockaert M, and Erikson T. The Impact of Top Management Team Characteristics and Board Service Involvement on Team Effectiveness in High-Tech Start-Ups. Long Range Planning 49(4) 2016: 447–463.

6 Liptsitz YY, Timmins NE, Zandstra PW. Quality Cell Therapy Manufacturing By Design. Nature Biotech. 34(4) 2016: 393.

7 Knockaert M, Bjornali ES, Erikson T. Joining Forces: Top Management Team and Board Chair Characteristics As Antecedents of Board Service Involvement. J. Bus. Ventur. 30(3) 2015: 420-435.

8 Ott D, et al. Life Cycle Analysis Within Pharmaceutical Process Optimization and Intensification: Case Study of Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient Production. ChemSusChem 7(12) 2014: 3521–3533.

9 Wellman K, Molinari C. Biotechnology Research: Raising the Stakes for Governance. Academy of Management Proceedings. 2015(1) 2015: 10398.

10 Engeli I, Rothmayr AC. When Doctors Shape Policy: The Impact of Self‐Regulation on Governing Human Biotechnology. Reg. Govern. 10(3) 2016: 248–261.

11 Coombs J. How a Large Biotechnology Company Teamed with a Translation Service Provider to Define Best Practices. J. Com. Biotech. 20(1) 2014: 49–53.

12 Bailey AM, Mendicino M, Au P. An FDA Perspective on Preclinical Development of Cell-Based Regenerative Medicine Products. Nature Biotech. 32(8) 2014: 721.

13 Sanderson J, et al. Towards a Framework for Enhancing Procurement and Supply Chain Management Practice in the NHS: Lessons for Managers and Clinicians from a Synthesis of the Theoretical and Empirical Literature. Health Services and Delivery Res. 3(18) 2015.

14 Block MJ. The Benefits of Alternative Dispute Resolution for International Commercial and Intellectual Property Disputes. Rutgers Law Rec. 44, 2017.

15 Sundaramurthy C, Pukthuanthong K, Kor Y. Positive and Negative Synergies Between the CEOs and the Corporate Board’s Human and Social Capital: A Study of Biotechnology Firms. Strategic Management J. 35(6) 2014: 845–868.

16 Wang X, Rivière I. Clinical Manufacturing of CAR T Cells: Foundation of a Promising Therapy. Mol. Ther. Oncolytics 3, 2016: 16015.

17 Taylor J, Vithayathil J. Who Delivers the Bigger Bang for theBuck: CMO or CIO? J. Strategic Information Systems 27(3) 2018: 207–220.

18 Davis BG, Serpell CJ. Editorial Overview: Nanotechnology and Biotechnology: Two-Way Traffic. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 46, 2017: vi–viii 2017.

Alison R. Carter is a research fellow, Edward Meinert is Sir David Cooksey research fellow, and David A. Brindley is senior research fellow in Healthcare Translation and group lead at the University of Oxford, Healthcare Translation Research Group, Department of Paediatrics, Oxford, UK; corresponding authors: [email protected] and [email protected].

You May Also Like