In Search of a CMO for My Biotechnology Startup: How to Navigate a Journey Without Process MapsIn Search of a CMO for My Biotechnology Startup: How to Navigate a Journey Without Process Maps

HTTPS://STOCK.ADOBE.COM

An innovative biopharmaceutical product can transform from an abstract idea at small scale into the basis of a burgeoning startup company. At that point, company leaders seek ways to ensure that a biologic will scale up in a quality-controlled, professional, and sustainable environment. That involves refining a research-stage prototype into a product that will be consistent and reproducible for research and development (R&D) and manufacturing and that will meet all relevant regulatory standards in specified target markets. Within the constraints of a small, early stage company with limited resources, however, making such refinements might be difficult or impossible.

To develop a product that meets the above standards, biomanufacturers are required to demonstrate critical quality attributes (CQAs) and critical process attributes (CPAs) for their manufacturing processes. Those concepts provide data-rich frameworks that can be monitored and maintained to ensure that end-product safety and efficacy (therapeutics) and safety and equivalence (devices) are controlled and recorded. In general, a manufacturing process (including characterization, validation, ancillary testing, and final product development) must advance into an industrial standard.

To use an everyday example, imagine an amateur baker who makes pizzas in a domestic kitchen but then starts selling homemade goods to neighbors. The word spreads of the high quality of the goods. The production capacity of the home kitchen is quickly exhausted, so the amateur — now turned semiprofessional pizzaiolo/a — seeks to move into a small industrial unit with large-scale equipment, industrial food hygiene standards, packing lines, and so on (1). That transition from research to industrialization also is required in biopharmaceutical development, with the equipment, documentation, personnel, and facility standards required to make a product for investigational use in a clinical study as described by good manufacturing practice (GMP).

In the example above, the pizzaiolo/a needs consistent access to a manufacturing facility because products must be made daily to meet the rate of consumption and/or spoilage. Conversely, most biopharmaceutical startup companies seek to manufacture a single product to support a phase 1 clinical trial. The product is made in a single batch and cryopreserved or lyophilized for storage. Thus, it is cost prohibitive to build a manufacturing facility, which will require significant operational and capital expenditures (OpEx and CapEx). That facility will be used to produce only three batches of a product for clinical trials — one batch each for an engineering run, a demonstration run, and a final GMP run. Contract manufacturing organizations (CMOs) and contract development and manufacturing organizations (CDMOs) support the increasing need for GMP manufacturing from startup companies and provide vertical integration and outsourcing in the biopharmaceutical industry (2, 3).

After developing a biologic, a startup company needs to make that product to a professionally acceptable standard. At that point, should the company sign a contract with a CMO or CDMO and leave the product with that organization to achieve that standard? Based on our experience and observations, that is not the optimal approach. CMO selection, relationship maintenance, and delivery can be intricate processes. When performed well, they are a studied and practiced. Often such processes can be improved with the help of experience, and they are always improved with diligence. Both the startup company and outsourcing provider must be prepared for a marathon rather than a sprint, engaging with both human factors and technical processes (4).

What Do CMOs Do?

Typically, a startup company develops a breakthrough therapeutic in a small laboratory after resource-intensive input yields promising results and diligently kept records. A CMO can help the company crystallize its processes. That is done by evaluating every step with the company, refining and streamlining processes, ensuring that steps to production are as efficient and safe as possible, and checking that procedures are reproducible by a third party.

A CMO will flag potential problems and work with a startup company to resolve manufacturing issues, whether such issues are caused by quality, regulatory, legal, safety, efficacy, cost, or other reasons. It is important that a startup company work closely with its CMO to keep a project on time and within budget.

If all goes well, the startup will be equipped with a final product that passes quality and regulatory requirements — characterized, validated, ancillary tested, and reproducible to an industrial standard. The product has been transformed from the artisanal to the professional. At that point, the startup company is ready to engage with regulatory authorities on later stage items, and the product can advance toward clinical trials.

Why Does a Startup Need a CMO?

A small startup company often cannot afford the large infrastructure costs related to building a development and manufacturing facility and hiring enough fully qualified and experienced skilled professionals for that facility. Consider also the low use rate of building a manufacturing facility that has use for limited output at this stage of the enterprise (5).

Two other factors have driven the need for CMO partnerships. The first is the increasing complexity of investigational medicinal products (IMPs), leading to increased interdependencies among manufacturing processes and CQAs. Consequently, process characterization and development expertise is critical for drug-candidate development programs, and a great deal of that expertise is concentrated in CMOs. The second factor is the need to fulfill imperatives from key stakeholders. Both large biopharmaceutical and small startup companies receive the same mandate from investors: Maximize both the rate of progress toward clinical trials and the return on capital employed (ROCE). Thus, having significant CapEx and OpEx for a manufacturing facility sitting on a company’s balance sheet is not an attractive financial proposition (6).

How Do You Select a CMO?

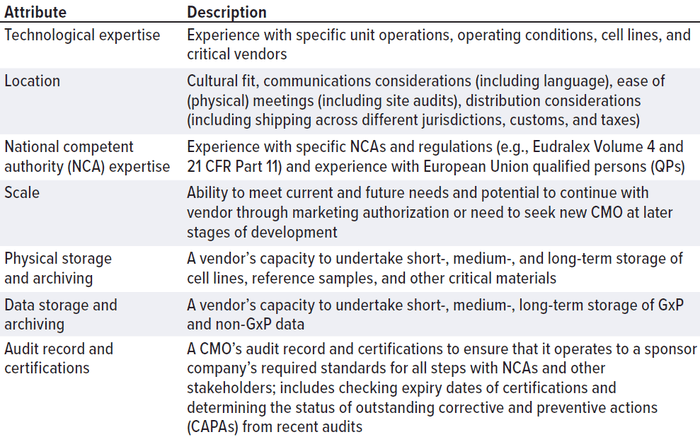

CMOs come in all sizes, jurisdictions, and specializations. They might have long lead times caused by international shortages in equipment, consumables, personnel, and/or facility availability. CMOs are a significant item of expenditure. If your startup company were to buy an expensive car, you would carry out appropriate due diligence, check its specifications, compare the make and model with those of other competitors on the market, and carry out a road test. Approach the search for a CMO in the same way. Don’t be afraid to assess the market thoroughly, carry out a price comparison, and check details thoroughly. Define your CMO “search space” (Table 1) in the same way that you would define the design space for an experiment.

Table 1: Contract manufacturing organization (CMO) differentiators can be used when

defining a “CMO search space.”

Define your requirements clearly. Formalize them and undertake a full request for quote (RfQ) and/or request for proposal (RfP) exercise with potential suppliers. Ask the difficult questions about their qualifications and expertise before you sign an agreement. Remember to evaluate a CMO beyond its sales team. You are unlikely to work with sales-team members after contract execution.

Although startup companies are experts in their own technologies, they are unlikely to know how to manufacture biologics to meet GxP requirements at different scales and with an acceptable cost of goods (CoG). Startups also lack experience in interpreting the specific “language” of CMOs and in distinguishing among CMOs. Most startup companies also do not understand the differences among multiple quotes, which often are written in a CMO’s own template and in a way that can be difficult to compare with quotes from other CMOs. Startup companies might not understand associated procurement rights, including carefully written legally binding agreements for large-ticket items. As such, only in rare cases, a small startup is best placed to coordinate a CMO RfP and selection process itself.

The appointment of a CMO is the most important vendor selection that a preclinical biopharmaceutical company undertakes, and often it is the largest budgetary commitment. We strongly recommend appointing independent consultants with expertise in CMO sourcing, evaluation, and management to coordinate that process and confer objectivity. Ultimately, using experts to help appoint a CMO will save a company time and money.

What Does a CMO Need to Get Started?

In life, it is rare that things fall neatly into place without a significant amount of hard work beforehand. Getting the paperwork, knowledge transfer, and flow of communications right at the beginning of a startup’s relationship with its CMO will pay dividends.

Paperwork: Three main contracts should be in place before a company and CMO begin detailed technical discussions and/or material transfer: a master service agreement (MSA), a quality agreement, and an initial statement of work (SoW) (3). It is often also helpful to have separate terms of reference documents agreed between the parties regarding communication methods, dispute escalation, and resolution procedures (at a more operational level than what is covered in the MSA), and a high-level project plan. The last should include approximate timelines and costs — including for SOWs yet to be signed between the parties. It is helpful to ensure clear expectation and interdependency management.

Knowledge and Material Transfer: Early in the partnership, working groups of key technical representatives from the startup company and from the CMO should convene to exchange product- and process-related knowledge. Such meetings should be minuted with clear actions identified. Where possible, data transfer should go through a central data room, including clear access logs and permissions. Similarly, all material transfer should be completed swiftly to minimize the risk of critical path delays, and a formalized register of any materials should be transferred prepared and regularly reviewed by the parties.

Culture and Communication: Although clear communication, objective setting, and monitoring are cornerstones to all vendor relationships, it is essential to to set the right tone and cadence for the collaboration at the beginning of those relationships. Both parties should be honest about personal communication style preference. If they are incompatible, both parties should be willing to exchange team members for those with a better cultural fit. Ultimately, better working relationships will lead to smoother and more successful projects for all parties.

What Is Key in the Management of a Startup–CMO Relationship?

The need for effective management of a CMO relationship is driven by two factors. First, effective project management and communications should maximize the efficiency of a CMC program and minimize execution risks. Second — and in our experience something that has proven to be an unpopular suggestion with some sponsors — startups engaging in CMC activities to produce materials for GxP nonclinical or clinical purposes must exercise GxP vendor oversight. Both requirements apply to all organizations engaging in GxP activities, regardless of the number of staff and the company’s funding stage and despite the resistance of a management team that might prefer to spend time and money on endeavors that seem at first glance to have a more direct bearing on breathing into life an innovative idea (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Regulatory requirements for sponsor oversight.

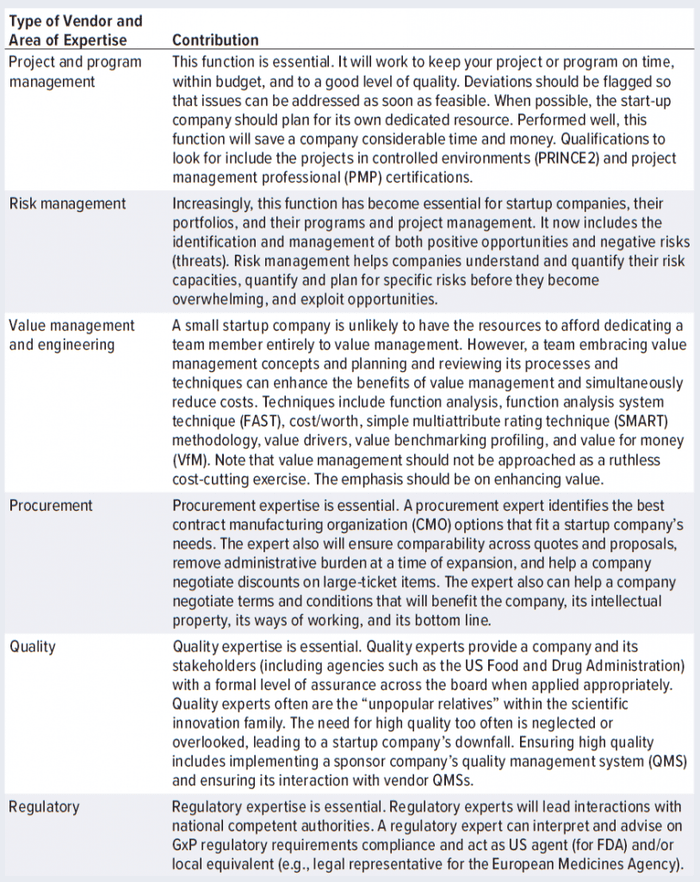

Which Vendors Can Help in the Startup–CMO Relationship?

Table 2 summarizes the types of experts who can help a startup company achieve a productive relationship with a CMO and who will be helpful during scale-up. A company already might have those specialisms on its team, but if not, it would be wise for the company to train existing team members, hire new staff, or work with consultants or relevant organizations with the appropriate expertise and experience.

Table 2: The relationship between a startup biopharmaceutical company and a contract manufacturing organization (CMO) includes many critical functions.

What Lessons Have Been Learned?

We hope that we have provided a good beginner’s guide to navigating the CMO journey. To conclude, we underline key lessons learned from experience in terms of behaviors and pitfalls that startup companies should avoid.

Don’t underengage and leave the work in the hands of a CMO, “hoping for the best” and believing that the service provider will understand the cutting-edge ideas in your head without translation or written formulation. Remember that you need to explain and monitor each step.

Don’t disengage if the relationship starts to go awry and a CMO does not meet your initial timelines. Instead, seek to understand why that has happened and find a solution together with the CMO.

Don’t overengage and attempt to micromanage people who have more expertise that you do in manufacturing. Understand, respect, and learn from each other’s skills.

Don’t close your mind to your own potential standard operating procedures (SOP) errors. Your CMO can help make your idea and processes work.

Remain mindful that GxP vendor oversight is not optional. Sponsors might delegate certain obligations to CMOs and contract research organizations (CROs), but they never delegate complete responsibility.

Plan, ask questions, and be prepared. Don’t get caught out by false and unresearched assumptions (e.g., false lead times).

Most important, remember to enjoy the broader travels with your CMO and other key providers as they help your idea take flight and move closer to realization.

References

1 Agnew H. Paris Entrepreneurs Tap into Millennials’ Taste for Italy. Financial Times 15 August 2017; https://www.ft.com/content/f9ae713a-80d3-11e7-94e2-c5b903247afd.

2 Carter A, Meinert E, Brindley D. Proposing a Systematic QbD Approach Toward Validated Guidelines for CMO RFI and RFP Processes: Biopharmaceutical Vendor Evaluation and Selection Minimum Standards (BioVesel). BioProcess Int. 16(10) 2018: 22–26, 52; https://bioprocessintl.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/16-10-Carter-Focus.pdf.

3 Brindley DA, Meinert E, Carter A. A Multistep Research Protocol to Develop and Implement Validated Guidelines for CMO RFI and RFP Processes: Biopharmaceutical Vendor Evaluation and Selection Minimum Standards (BioVesel) BioProcess Int. 16(11–12) 2018: 12–15; https://bioprocessintl.com/manufacturing/manufacturing-contract-services/a-multistep-research-protocol-to-develop-and-implement-validated-guidelines-for-cmo-rfi-and-rfp-processes-biovesel.

4 Bag S. Supplier Management and Sustainable Innovation in Supply Networks: An Empirical Study. Global Business Review 19(3 suppl) 2018: S176–S195; https://doi.org/10.1177/0972150918760051.

5 Yang O, Qadan M, Ierapetritou M. Economic Analysis of Batch and Continuous Biopharmaceutical Antibody Production: A Review. J. Pharm. Innov. 14, 2019: 1–19; https://doi.org/10.1007/s12247-018-09370-4.

6 Siganporia CC, et al. Capacity Planning for Batch and Perfusion Bioprocesses Across Multiple Biopharmaceutical Facilities. Biotechnol. Prog. 30(3) 2014: 594–606; https://doi.org/10.1002/btpr.1860

Corresponding author Alison R. Carter ([email protected]) is senior partner, and David A. Brindley is managing partner at Biolacuna, Belsyre Court, 57 Woodstock Road, Oxford, OX2 6HJ, UK; 90 Canal Street, 4th Floor, Boston, MA02114, USA.

You May Also Like