How Project Management Fits into the Drug Development ContinuumHow Project Management Fits into the Drug Development Continuum

Once upon a time, this was the way of things: Most projects happened in-house, or at least locally, and the activities they required weren’t very complicated. In today’s global business environment, however, the days of such simplicity are gone. Instead, now the “+1” person in the N + 1 equation (see the box at right) is the glue that holds complex, global activities together for a company. That person is the project manager.

Simply stated, project management (PM) is the management of people, activities, time, and money toward the successful completion of a stated goal. That sounds easy, and we do it all the time in our daily lives. But it is imperative in the complex world of biopharmaceuticals to have a single point person responsible for ensuring that all the pieces of a project come together efficiently, effectively, and on schedule.

Picture This: First, consider the management of people. Imagine you are team leader of a group responsible for delivering a phase 1 clinical trial antibody product. You’re excited to be chosen as a team leader because it is an excellent chance to develop your career. Of course, it comes in addition to your regular technical responsibilities. You are also personally responsible for the expression, filtration, and purification of the antibody.

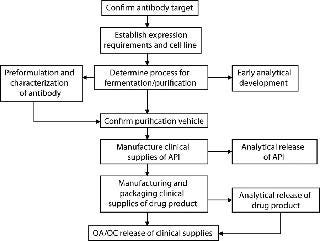

As team leader, you need to coordinate with various functional groups including analysts, formulators, and clinical manufacturing personnel — and even clinicians — to outline the activities that must be accomplished to get the product to the clinic. To that end, you create a flow chart like that in Figure 1. You meet with your team every week to discuss the status of the program, going through the chart step by step to ensure that everyone is working together to meet an impossible timeline. The work is hard, intense, and time-consuming, but progress is made. You have a cohesive team progressing at an acceptable pace.

THE CLASSIC VIEW

Q: How many technical personnel does it take to complete a project?

A:N + 1 (“We’ll throw in as many as it takes to get the product out the door.”)

Q: How many project managers does it take to complete a project?

A: Zero (“They don’t do anything really meaningful, anyway.”)

Figure 1: ()

Now the antibody is purified, and it’s passed off to the analysts and formulators. They work with the clinical manufacturing group to scale up and make the full formulation batches. The finished product goes to release testing laboratories at the same time it goes to the clinical packaging group for labeling. Then the drug is found to be within specifications and can be released for shipping to the appropriate test sites for clinical trials — just as the f low chart says, and just in time.

But someone forgot to include shipping personnel in the project team so they would know that this particular antibody had to be kept cold. Neither were they told that the product couldn’t be shipped on Fridays because no one would be at the clinic to receive it over the weekend and store it at the necessary 5 °C. So the precious drug was shipped at ambient summer temperatures and sat on a loading dock for nearly 48 hours. Oh no!

You get a call on Monday morning and find out that whole clinical program is now delayed by months because no one managed the shipping department. And this is the moment when you, as team leader, wish that you’d had a project manager on the case.

Doing Something Meaningful: Among other things, a project manager’s role and responsibility is to ask the right questions of the project team to ensure all the appropriate steps are taken and the program is executed as expected. This person’s role also includes outlining all pertinent operations, keeping track of how they interact with one another, and making sure all appropriate people are included and informed — and have approved — of the process. For example, the project manager would have apprised the shipping department of that hypothetical drug’s logistical issues.

PM activities extend not only to the team responsible for tactical operations (e.g., scientists, manufacturing, and shipping personnel), but must also include management (strategic operations). Upper/executive managers typically establish a program definition in the first place. Their strategic vision needs to be translated and communicated to the tactical team so all involved are clear about expectations. It is a project manager’s responsibility to take that vision and track it for the team to ensure that the members stay true to its intentions. A project manager can also help them prepare and present their strategy for the overall plans and mitigation of risks to upper management through well- crafted and well-placed questions. Finally, if something goes wrong — and it inevitably will — the project manager is often faced with tempering the expectations of upper management so that they understand what has happened and why.

In many companies, team leaders double as project managers. Sometimes this works, especially if those people are well versed in the entire chain of events from start to finish of a program, including events outside their own areas of expertise. Often, however, a team leader also has his or her own activities to address, which can consume a lot of time and effort beyond project management.

It can help a team tremendously to have one person who is fully and completely responsible for managing all activities and communications through meetings, minutes, and other interactions. An assigned project manager can also track the details of all resources — personnel and otherwise.

Managing Resources

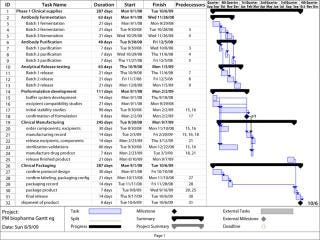

Credit for the introduction of current project management practices goes to Henry Laurence Gantt, an industrial engineer who introduced the Gantt chart (Figure 2) nearly a century ago. Further advancements in project management and control produced other PM tools such as the program evaluation and review technique (PERT) and critical path management (CPM) tools. Now computer simulation models are available. But the ubiquitous Gantt chart is probably the most commonly used method of managing the multitude of events that make up a program. Gantt charts track more than just activities; they track activities, time, and resources all together.

Figure 2: ()

Communication is key to all that, and Gantt charts are only a means to the end. They can track just a few tasks or delineate a plethora of tasks. The number of tasks included should reflect only those needed to ensure proper communication and effective execution. At critical junctures, some detail may need to be added (such as shipping in the above example). If that improves performance, then do it. If you find, however, that your team spends more time updating its Gantt chart than doing the actual work it’s meant to track, then use some other tool.

Utility of a Gantt Chart: In a Gantt chart, activities are listed down one side (typically the left) with their time frame listed across the top. The body of the chart depicts the length of a given activity by placing a bar along its row. As an activity progresses, its bar changes color depending on the percentage that is complete.

Software Gantt charts can be very helpful because dependency of one activity on another can be electronically established. For example, release testing of a drug substance can’t happen until the drug is made. So release testing would begin at the end of drug substance manufacture (“finish to start” as in Figure 2). Once all dependencies are established in the electronic Gantt chart, the overall rate-limiting steps (the critical path) toward the goal can be observed with the click of a button at any time, even in the most complicated of programs.

Gantt charts can also help project managers flesh out the resources required for each activity, sometimes by attaching a person’s name to each activity. The benefit of such an apparently small step is that the entire team then knows who is accountable for what. So each team member can track activities as they relate to his or her part of the process, which encourages “buy-in.” This also means that each team member can keep others abreast of changes in a plan that may seem tiny at first, but that could have great impact down the line.

Another way resources can be tracked in a Gantt chart is by assigning equipment or facilities to specific tasks. This can ensure that no two activities requiring the same resource are scheduled at the same time. For example, when only one fermentor is used for production of a specific drug substance, but five lots of the same substance are required. The specific fermentor can be listed on a Gantt chart for each batch, so the software warns users who try to schedule other production lots at the same time. This technique works for all resources, including personnel. It can also be used to justify more resources of any kind (such as people when the chart shows that a team is already working at 300%).

Project Management in Biopharmaceutical Development

A biopharmaceutical project manager is best served with a good working knowledge of the drug development process. Such knowledge will help him or her map goals — and understand what they mean to the company as well as what resources are required to reach each goal — and estimate how much time and money will be required to attain those goals. Each company has its own estimates, but the types of tasks are the same for all biopharmaceutical development.

For an innovator company developing a new antibody, for example, the starting point is identifying the target gene sequence for the therapeutic indication in question. Once a promising sequence is identified, the next step involves getting that target DNA structure into an appropriate cell line and using that cell line to express a needed protein in commercially feasible amounts. All this appears to be straightforward, but it usually takes years.

Once expression is confirmed, process engineers scale up production and purification to a level that’s appropriate to make toxicological evaluation supplies. The engineers determine parameters for production and work with protein formulators to confirm a final vehicle that will provide the best product stability. Along the way, bioanalytical chemists work out appropriate tests to confirm that the protein is correct, present at the necessary concentration, and functioning as needed.

Finally the overall processes are established, and material is manufactured (and typically supplied to a sterile fill–finish operation) and then shipped to a toxicology group. If the drug is successful at that phase, work begins on scaling up for phase 1 studies in humans, then starts over for phase 2 studies, and finally full-blown phase 3 “pivotal” clinical trials that establish the overall efficacy of a new drug.

Throughout that process a company maintains contact with regulatory agencies and files appropriate documents at each stage. For example, the investigational new drug (IND) application is required before phase 1 (“first-in-human”) studies are initiated. And, of course, the biologics license or new drug application (BLA, NDA) is submitted for final approval.

PROJECT-RELATEDAND PROJECT MANAGEMENT CONSIDERATIONS

Project Definition: defined scope and timeline; modular approach to completion of tasks; include appropriate PM tools (e.g., Gantt chart), well-delineated resources and personnel, and flexibility in the mode of execution

Project Risk Analysis: appropriate risk assessment; mitigation plans to minimize risks; contingency plans to minimize impact of risks that may occur

Defined Communication Pathway: open communication channels throughout the project continuum; minimal hierarchy; team expectations clearly defined (results oriented rather than task oriented); team email/phone numbers and/or other contact information provided; regularly scheduled team and management meetings; commitment and accountability of team members and their management

Although obtaining regulatory approval is a major milestone, it is not the end of the road, but rather just the beginning of a new one. The project team then begins to work toward technical transfer and product launch activities. Those may include further scale-up work, additional refinements of analytical procedures, transfer of methods and processes to a final manufacturing site, qualification of equipment and processes, and so on. Activities such as shipping validations, supply chain development, and sales force training might also be part of this phase, depending on the nature of the team. Each activity can be broken down into as much detail as needed to ensure an effective execution.

Nonetheless, as a drug program moves toward commercial supply, the team cannot afford to forget the product’s end users. Often several items will change once a product reaches its eventual manufacturing site. Small matters include the color of the seal cap that goes onto each vial. The technical team may agree to use a different cap (with a different color) because it works with the production sealing and inspection equipment more efficiently. But the marketing group may have already published their materials for launch showing the original color. And that could cause trouble and even delay the launch.

Additional Challenges: Most of this discussion assumes that the team members are all employed by the same company. Often, however, they are not, even though they may share the same overall goal. Even so, savvy project managers know that their companies may not share quite the same interests. This is especially true when contract research organizations (CROs) and contract manufacturing organizations (CMOs) are involved. Project managers in all companies share the same challenge in ensuring that all their team members work toward the common goal despite uncommon interests.

This is even more of a challenge in acquisitions and mergers. Managing a program when a company is being taken over and its personnel aren’t certain of their personal and financial future changes from simply tracking activities and resources into coaching each member toward the goal based on personal integrity. The politics of a merger can either energize or denigrate the energy and synergy of a project team.

In the end, communication and commitment are key for all teams. A project manager’s dream is to lead team members who communicate and perform, even when it is personally inconvenient, for the benefit of the team and its goal.

Whose Side Are You On Anyway? In today’s business environment, companies often outsource their work to optimize materials, equipment, and time. When a program moves outside the company, its project team relies on outside team members to engage and execute toward the goal with the same level of commitment as internal team members.

Although the goal is the same (to get the product out the door), the agenda of one side in a contract arrangement doesn’t always match the other. For example, consider you decide to expand your fermentation capability through a toll manufacturer when you recognize that you have only three in-house fermentors but need six to meet the timelines. You also want the contract manufacturer to purify the product by ultrafiltration rather than ship unpurified material back to your facility and risk deactivation of the antibody.

You and the other members of your team perform due diligence at the CMO’s plant site. It seems to have the necessary equipment, its staff seems to understand good manufacturing practice (GMP), and their documentation appears acceptable. So you negotiate terms and sign a contract with milestones your project manager has outlined in the Gantt chart for completion.

After the kickoff meeting, you begin regular meetings and activities as outlined on the Gantt chart. But you realize that the CMO’s timelines seem to be slipping. Your company’s agenda is to get its product out the door and start clinical trials as soon as possible. The CMO wants to fulfill your contract while maintaining its overall bottom line. Even though the two teams are aligned regarding the stated goal and associated milestones, the CMO’s internal list of activities contains much more than just your work.

A good project manager knows up front how such activities can affect results and watches for them as a program begins off-site. Fortunately, your project manager has run into this type of situation many times before. Based on previous experience, she has already contacted the other company’s project manager and expressed concern over the trend in delays. Not only that, but the CMO’s culture identifies its project manager assigned to you as a champion for your program. Thus, when your project manager talks with the other, that person starts immediately (behind the scenes) at the CMO to realign resources internally and ensure that the CMO doesn’t lose track of your timelines. You exhale a sigh of relief because someone is taking care of the program, which allows you to focus on your technical and team leader responsibilities.

Crisis Management

Your program proceeds along the Gantt chart that you developed at the start. Potential delays due to misalignment of the CMO’s resources and efforts have been averted. Smooth sailing, right? Not necessarily.

Material is manufactured and purified at the CMO and released for shipment based on methods that it has transferred into its facility from yours. Now the material arrives at your site and is retested for acceptance. And it fails — miserably.

How can this be? Your company developed and validated the methods. They were duly transferred from one site to the other following a proper protocol-driven procedure. What could have gone wrong?

An investigation ensues. You are concerned because you know how long investigations can last. You need to mobilize yourself and your technical team immediately. As team leader, you are immediately relieved that you have an excellent project manager on the case. She brainstorms along with you and your team, and she takes the lead in setting up meetings and communication lines between the two companies’ management, technical staff, and quality units.

Because the project manager can provide the necessary assistance, you can provide the salient points at management communication meetings as needed, with minimal interruptions as you apply yourself to resolving the technical problem. The project manager helps to organize and run your technical meetings too, providing agendas and meeting minutes so that all activities are documented for the investigation. Similarly, she ensures that your quality unit remains up to speed on the developments at hand. That helps your team ensure that quality requirements for documentation and investigation are all met adequately and on time according to the standard operating procedure (SOP).

Eventually, through detailed discussions with all parties on both sides of the table, the team discovers that a well-meaning purchasing agent at the CMO had recently ordered a “similar” column because it was less expensive than the originally validated model. You have all learned the hard way that similar is not necessarily the same. Because of efficiencies that your project manager has provided, however, coming to this conclusion and completing the associated documentation were timely.

The Best “+1” People

The “Considerations” box lists the basic attributes of good project management — and, by extension, a good project manager. A highly complex project needs a defined scope with definite deliverables; without those, it constitutes an operational activity (work continuum). Projects are usually modular in design to facilitate their completion. Proactive project managers must be clear about program goals and have an appropriately charted plan to achieve them. Even with that plan, good project managers recognize the importance of flexibility and always have risk mitigation plans in mind — as well as possible contingency plans to address unavoidable perturbations that inevitably occur to bring the project back under control.

A project manager should have a long-range perspective of the entire project, so he or she is not only anticipating the next hurdle, but also ensuring that the team negotiates all relevant hurdles. The project manager needs to be strong and directive, but restrained in decision-making, allowing the project team to weigh in and create a path forward to ensure a fully developed response to issues that may arise. Lines of communication must be open, and a healthy dialogue among team members is essential. When a project is well managed, its goal is met on-time and within budget. The results will be of a quality that does credit to the entire team.

About the Author

Author Details

Leonore Witchey-Lakshmanan, PhD, is senior director of GeneraMedix Inc., where she is directly responsible for drug development from API characterization to drug product launch. Dr. Witchey spends a considerable amount of time managing projects and working with project managers across companies and cultures. Corresponding author Hazel Aranha, PhD, RAC, is president of GAEA Resources Inc., PO Box 428, Northport, NY 11768; 1-631-261-4665; [email protected]; www.gaeainc.com. Her company focuses on regulatory and compliance consulting and medical communications.

You May Also Like