A Product–Packaging Interaction Study to Support Drug Product DevelopmentA Product–Packaging Interaction Study to Support Drug Product Development

June 1, 2018

ADOBE STOCK (HTTPS://STOCK.ADOBE.COM)

Drug packaging is subject to a number of regulatory requirements, including those for product containers and packaging. For example, according to the federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (FD&C) section 501(a)(3), a drug is considered adulterated “if its container is composed, in whole or in part, of any poisonous or deleterious substance which may render the contents injurious to health.” And 21 CFR states that drug packaging “shall not be reactive, additive, or absorptive so as to alter the safety, identity, strength, quality, or purity of the drug beyond the official or established requirements.”

Such requirements are enforced by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA). The agency has produced guidance on submitting an application for a new drug product, focusing specifically on the information required about the packaging materials: Guidance for Industry: Container Closure Systems for Packaging Human Drugs and Biologics (1). It states that an application must show through analytical review and evaluation that a drug’s proposed container and its components are suitable for intended use. Along with the FDA, the Consumer Product Safety Commission (CPSC) and the United States Pharmacopeial Convention (USP) set standards and enforce regulatory requirements for the control of drug packaging and delivery systems.

When considering a drug’s packaging, a company must assess both the packaging as a whole and its components. FDA’s guidance defines a packaging component as any single part of a packaging that contains and protects a drug product, including containers (e.g., vials and bottles), closures (e.g., screw caps and stoppers), and container labels (1). The sum of the packaging components is referred to as the container closure system or packaging system.

Extractables and Leachables

A leachable is a chemical compound that migrates into a drug formulation from a material that is in direct contact with a drug (e.g., plastic, glass, and stainless steel) under the recommended conditions for use and storage. An extractable migrates from a direct-contact packaging material when exposed to a solvent and to exaggerated time and temperature conditions. Thus, leachables typically are considered a subset of extractables.

A leachable can affect both the safety and efficacy of a drug. By first examining the extractable compounds of a drug’s packaging under exaggerated conditions, a company can identify possible targets for leachables studies (2). Extractables and leachables (E&Ls) studies are important both to protect patients and to comply with regulatory requirements.

Product–Packaging Interactions

Studying interactions between a drug product and its packaging is crucial because of the complex nature of such interactions. A number of materials are used in drug packaging, and the variations in active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs), excipients, and solvents in drug dosage forms are many. In each case, the combination of product and packaging and thus their interactions will be different, creating unique problems and issues to consider (3).

If the packaging of a drug is changed, a manufacturer should conduct product–packaging interaction (PPI) studies to assess the effect that change might have and to ensure continued regulatory compliance.

Regulatory History and Degree of Concern

The study of leachables in drug products first came about as a result of cases of patient sensitivity and other related safety concerns caused by leachables in the 1980s (4, 5). This is the point at which the FDA began to address leachables in drug products formally and comprehensively. Since then, our knowledge and understanding of E&Ls has continued to grow.

In 2015, USP published two general chapters on E&Ls (6): USP <1663> on extractables (7) and USP <1664> on leachables (8). These chapters provide an update to the existing regulations and guidances, presenting a framework for the design, justification, and execution of E&L studies. Although the chapters do not outline specific experimental conditions or tests, they establish critical dimensions that should be considered during assessment of E&Ls, discussing practical and technical aspects of each dimension.

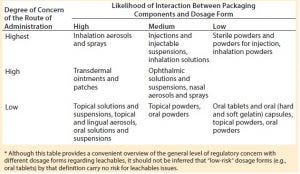

Table 1: Examples of packaging concerns for common classes of drug products* (8)

The amount of information about a drug’s packaging system required in a regulatory process depends on a product’s dosage form and route of administration. A liquid dosage form is more likely to interact with packaging components than is a powder or a solid. Drug products that are administered directly (e.g., those delivered straight into a patient’s lungs through a spray) will pose more safety risks of adverse interactions than those that are not. Thus, more detailed information usually is required about packaging for an injectable drug product or for an inhalation product than for that of a solid oral dosage form (Table 1) (1).

Extractables and Leachables Studies

Leachables from a drug-packaging system can pose considerable safety risks to patients. In some cases, they can cause toxicity, carcinogenicity, immunogenicity, and endocrine dysregulation (2, 9). Interactions among a leachable, an API, and excipients in a product vehicle can alter a product’s physicochemical properties, thus affecting the drug’s quality and efficacy (2). Evaluation of leachable compounds in drug packaging components is a critical stage of drug development. To assess E&Ls in a packaging system, it is important both to identify the source of E&Ls and to have analytical tools with which to detect them.

An E&L study begins with an extractables study to determine (under exaggerated conditions) the extractable compounds present in packaging components. This serves as a screening method to identify targets for leachables analysis. Once targets are identified in an extractables study, they can be monitored over extended periods of time in a subsequent full leachables analysis.

A wide range of analytical tools and technologies can be used in E&L studies. Although generic screenings are a great starting point, test methods must be tailored to focus specifically on the intended use of a drug packaging system and to determine appropriate sensitivities based on the exposure of patients to the final drug product. Technologies selected in E&L studies can differ depending on materials used, their intended purpose, and the appropriate sensitivities.

Some techniques and analytical methods used in E&L analysis include

Solvent extraction, including ultrasonication, microwave, automated solvent extraction (ASE), and Soxhlet extraction

Gas chromatography (GC) coupled to mass spectrometry (MS) or flame ionization detectors (FID)

High-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) coupled to diode array UV detector and tandem mass spectrometry (HPLC-DADMS/MS)

Spectroscopy with Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) and nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR)

Inorganic analysis with inductively coupled optical emission spectroscopy (ICP-OES), inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS), and atomic absorption spectroscopy (AAS).

Such techniques are used to analyze different drug delivery systems, including inhalers, injectables, medical devices, and blister packs. Choosing the most applicable methods and technologies and having an effective E&L program can save significant time and cost in a drug development process and can help manufacturers potentially avoid pitfalls, thereby reducing the overall time to market.

PPI Studies

Most studies of the interaction between a drug product and its packaging assess the effect of a change to a product’s delivery and storage devices. Such changes can include a simple modification to a component, a substitution of a component, or the implementation of a new device. Assessing the effect of a change is vital both for meeting regulatory requirements and for patient safety.

The approach to PPI studies is more concise than for a full E&L analysis. A PPI study protocol involves first subjecting packaging components to forced extraction under exaggerated conditions. Both organic extractable compounds (nonvolatile, semivolatile, and volatile) and inorganic extractable species are characterized through this method. Extractables detected in this analysis are used to determine potential target leachables.

The final drug-product formulation is analyzed for the presence of identified targets. This analysis is conducted under accelerated aging conditions to determine which targets affect a product. Product samples tested following this approach can include toothpastes, mouthwash, ophthalmic solutions, skin creams, and topical products, and so forth. Techniques used in a PPI analysis mirror those used in full E&L analysis (such as those in the E&L studies section above). Through a carefully designed and executed PPI study, concise and cost-effective evidence in support of product efficacy and regulatory compliance can be gained.

Importance of a PPI Study

With increasing regulatory pressure that has been developing since the 1980s, pharmaceutical companies are under considerable strain to investigate extractables and leachables as well as potential interactions between a dosage form and its packaging system. Thus, full E&L analysis are vital for applications for new drug products and PPI studies on changes to packaging components.

Tailoring such studies to fit the unique interactions between dosage form and packaging components is key. A bespoke E&L program will identify and quantify the compounds present in packaging components as well as the likelihood of clinical exposure to those compounds. A well-designed PPI study can help manufacturers minimize risks associated with changes in packaging components, providing concise and cost-effective evidence to support product efficacy and regulatory compliance.

An E&L program that is not fit for purpose can waste immense resources in terms of both time and budget. Hence, a carefully designed and implemented study can save significant time and cost in a drug development process and help manufacturers to avoid pitfalls, thus reducing time to market.

References

1 Guidance for Industry: Container Closure Systems for Packaging Human Drugs and Biologics. US Food and Drug Administration: Rockville, MD, 1999.

2 Markovic I. Evaluation of Safety and Quality Impact of Extractable and Leachable Substances in Therapeutic Biologic Protein Products: A Risk-Based Perspective. Expert Opin. Drug Saf. 6(5) 2007: 487–491; doi: 10.1517/14740338.6.5.487.

3 Annex 9: Guidelines on Packaging for Pharmaceutical Products. WHO Technical Report Series, No. 902. World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2002.

4 Leachables and Extractables Handbook. Ball D, et al. Eds. John Wiley and Sons: New York, NY, 2012.

5 Schroeder A. Leachables and Extractables in OINDP: An FDA Perspective. PQRI Leachables and Extractables Workshop, Bethesda, MD, 5–6 December 2005; http://pqri.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/pdf/AlanSchroederDay1.pdf.

6 ECA Academy. New USP General Chapters on Extractables and Leachables: <1663>, <1664>. GMP News 2015; www.gmp-compliance.org/gmp-news/new-usp-general-chapters-on-extractables-and-leachables-1663-1664.

7 USP <1663>. Assessment of Extractables Associated with Pharmaceutical Packaging/Delivery Systems. US Pharmacopeial Convention: Bethesda, MD, 2015; www.usp.org/sites/default/files/usp_pdf/EN/meetings/workshops/m7126.pdf (accessed 15.03.2017).

8 USP <1664>. Assessment of Drug Product Leachables Associated with Pharmaceutical Packaging/Delivery Systems. US Pharmacopeial Convention: Bethesda, MD, 2017; www.usp.org/sites/default/files/usp_pdf/EN/meetings/workshops/m7127.pdf.

9 Northup SJ. Assessing the Biological Safety of Extractable and Leachable Chemicals in Pharmaceutical and Medical Products. Am. Pharm. Rev. 8(4) 2005: 38–43.

Mike Ludlow is technical study manager for LGC’s CMC analytical services; 44-1638-720 500; [email protected]; www.lgcgroup.com.

You May Also Like