Pharmaceutical Manufacturing Quality Assurance Programs: Transitioning from Research and Development to the ClinicPharmaceutical Manufacturing Quality Assurance Programs: Transitioning from Research and Development to the Clinic

On average it can take or even exceed US$1 billion to get a pharmaceutical product to market, and nine out of 10 products developed never make it to commercialization (1). As technology advances, more potential therapies and preventatives are being developed and optimized by virtual companies. They are typically small, newly formed organizations that build their momentum on programs for novel products. Because many of the program activities are outsourced, virtual start-up companies developing pharmaceutical products raise concerns about ensuring product quality and regulatory compliance. Below, we analyze attributes to phase-appropriate quality assurance programs during research and development (R&D) into clinical studies. We focus on quality requirements needed to manufacture a compliant product at the appropriate phase of development for that product. Finally, a few case studies show how quality assurance has supported virtual and/or start-up companies.

Starting Points

Developers of new technologies or products can be uncertain about the critical steps needed to move a product to the next phase of development. Many start-up managers are uncertain about how to support their advancing programs, such as through regulatory interactions and clinical studies. A company might have completed a few preliminary nonclinical (animal) studies demonstrating product efficacy, or it might have a successful investigational new drug (IND) application but no quality system in place. Such common starting points represent a normal progression for incorporating phase-appropriate quality systems.

Herein, we discuss key elements for a small or virtual company attempting to further a pharmaceutical product from development to clinical phase 3. To help resolve questions about which regulatory requirements apply to phase 1 clinical studies, we also outline phase-appropriate quality controls that take priority during creation of a quality system. One of our case studies illustrates progression of a quality- management system (QMS) following a clinical-phase–based approach. The other two cases illustrate how ad hoc quality support can help keep your company and product compliant with US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) requirements and how that can be more broadly applied. By analyzing needs based on phase, we can outline key requirements, common successes, and areas for improvement when establishing phase-appropriate quality controls enable clinical-subject (human) safety and regulatory compliance.

Product Life Cycles

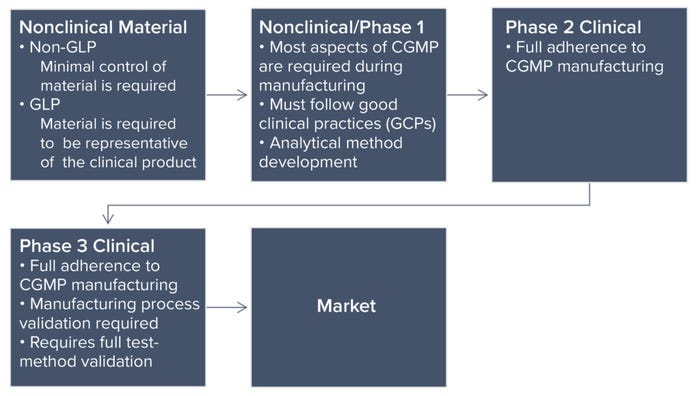

Phase-Appropriate Controls: Each phase of a product life cycle requires a different level of control. The most rigorous level is for marketed products. Typically, pharmaceutical companies require the involvement of quality professionals beginning with data reviews for nonclinical test results. Following nonclinical studies, a company progresses to managing development batches and engineering runs, a process in which the organization tests systems and equipment by running a manufacturing process to make production-scale material. Analytical methods also undergo method development to achieve qualification (phase 1) and validation (phase 2) later on. Once successful, the company proceeds to current good manufacturing practice (CGMP) operations and ultimately secures a move to clinical trials with the end goal of a marketable product. Manufacturing requirements and quality controls become progressively more stringent because of the numbers and health conditions of people receiving a drug (Figure 1: Phases of pharmaceutical product development and quality assurance control differences).

Figure 1: Phases of pharmaceutical product development and quality assurance control differences.

R&D Through Nonclinical Studies: Although we focus herein on development of QMSs and the quality controls surrounding them, different manufacturing standards apply to test articles used in nonclinical development. Early stage animal studies typically are conducted without compliance with good laboratory practice (GLP), often using different variations of a product to support an ultimate selection of the version that will go forward. Material used in current GLP (CGLP) studies — later-stage animal studies — must represent the phase 1 clinical trial material. In a CGLP study, the material must be consistent with what is proposed for clinical use. In addition, its manufacturing process must be similar or identical to that used for producing clinical material.

Quality oversight must ensure that a test article is suitable and released for use in both non-GLP and CGLP studies. R&D and nonclinical studies focus on current good documentation practice (CGDP), which is an FDA requirement (see the “General Requirements” box). The quality department works in tandem with process scientists to verify that items (e.g., logbooks, protocols, and reports) have documented all actions and activities fully.

Phase 1 Clinical Studies: As companies progress into phase 1 clinical trials, controls surrounding test materials (drug, therapy, or preventative product) must increase. The requirements are detailed in the Code of Federal Regulations (CFR) part 211 (2), which implements section 501(a)(2)(B) of the Food, Drug, and Cosmetic (FD&C) Act. However, those regulations are directed at the commercial manufacture of products typically characterized by large, repetitive, commercial-scale batch production and warehousing. Regulations that address validation of manufacturing processes (§211.110a) apply to the former, and §211.142 applies to the latter (2). Thus, those regulations may be inappropriate to the manufacture of most investigational drugs used for phase 1 clinical trials.

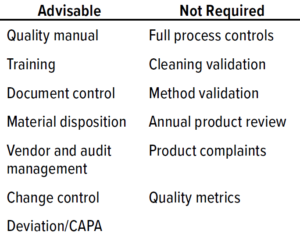

Table 1: Phase 1 quality-management system (QMS) documentation (CAPA = corrective and preventive actions).

For a phase 1 clinical study, test materials must comply with CGMP requirements to ensure human subject safety but do not need to comply with all CGMP requirements (Table 1: Phase 1 quality-management system (QMS) documentation (CAPA = corrective and preventive actions) 1). Although a full QMS is not required for phase 1, a virtual company must ensure that procedures are in place to dictate how to manage outsourced activities and safeguard data integrity. Table 1 suggests advisable processes that are not comprehensive starting points for phase 1 procedures and documentation.

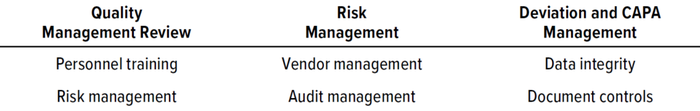

At this phase, having a quality manual is not a requirement, but it is an industry standard. The manual can contain many stated requirements that will be refined further and broken out into detailed individual procedures further along the product-development pathway. Table 2 lists examples of responsibilities within a QMS for a virtual company. In addition to the elements listed, clinical procedures are needed to support a sponsor’s clinical activities and level of involvement.

Table 2: Phase 1 QMS (CAPA = corrective and preventive actions).

Phase 2 Clinical Studies: The QMS will continue to evolve if a company chooses to move to the next stage, a phase 2 clinical study. About 70% of products from phase 1 go into phase 2 clinical studies (1). Upon successful transition into phase 2 studies, the key difference in requirements is a need for validation of systems and analytics.

At this stage of product development, companies should be working to finalize manufacturing processes. The QMS will be enhanced further at this phase by adding elements for safety reporting, stock recovery, and retrieval of unused product (if not already addressed in phase 1). At this point some sections of a quality manual can be pulled out and defined into standalone procedures. Depending on the time span between studies, some or most procedures will have had at least one review cycle to develop and be fine-tuned. A fully qualified list of vendors should be chosen based on potential risks.

Phase 3 Clinical Studies: About 3% of products transition from phase 2 to phase 3 (1). Manufacturing processes for phase 3 materials are consistent with those indicated above for phase 2. Methods and analytics require full validation, with release tests and specifications set in place. The QMS at this point should be fully mature, with additions such as annual product reviews and quality metrics.

Quality deviations such as serious adverse events, rejections, or product recalls can incur significant costs. At this point in a process, it is crucial for senior management and executive teams to prioritize the QMS. In addition, quality-system protocols and procedures should be implemented companywide. Quality is not just a checked box, but rather a holistic system that can lead to success or failure for a drug company. Thus, being educated about and mindful of quality requirements and regulatory expectations at each phase is critical to position your company for success.

Case Studies

Full Company Involvement to a Successful IND: A virtual cancer therapeutics company was finishing nonclinical (animal) toxicology studies and beginning to draft an IND submission. The company employed a small group of scientists but had no in-house quality-assurance employees. With no QMS in place, the organization required experienced oversight of its outsourced activities as it built one from the ground up.

Solution: By working with consultants on the big-picture quality issues, the company was able to respond to inquiries from a pre-IND meeting and incorporate basic procedures to govern critical ongoing quality activities. Specifications were formalized to inform and assist with the writing of the IND. Disposition procedures were implemented to ensure that when the IND was active (safe to proceed), the drug product would be released and ready for labeling and shipment. With a phase-appropriate QMS and ongoing vendor management and audit support, the company was prepared to move into phase 1.

Audit Support and Vendor Management: A virtual vaccine company with a global presence had four vaccines at different phases of clinical trials. It had limited staff and outsourced all operations. Although the company had an established quality team and QMS, it needed to outsource vendor audits ad hoc to a third-party supplier because of bandwidth limitations.

Solution: Consultants managed the client’s audits to ensure compliance with applicable regulations. The lead auditor contacted the supplier to request an audit, drafted an audit agenda, reviewed requested documents, and traveled to conduct the audit on site. Afterward, the team drafted a comprehensive audit report and signed off on an approved auditor cerificate. The consultants managed all mitigations of identified deficiencies. The sponsor was able to continue operations with no lapse in approved suppliers.

Document Transition to an Electronic QMS: A virtual drug company had an established QMS compliant with CGMP regulations. As this sponsor approached phase 1 clinical trials, its QMS consisted of a growing list of standard operating procedures (SOPs) and training programs. This resulted in the company choosing to migrate its existing QMS to an electronic quality management system (eQMS).

Solution: Consultants helped the company identify a user-friendly product that met its current needs, with 21 CFR Part 11-compliant signatures built in, and that allowed room for growth as a product moved toward commercialization. Following selection of the eQMS, advisors offered continual support by attending vendor demonstrations and helped the client beta-test the system before going “live.” Additionally, consultants created step-by-step training documents to help introduce the new eQMS to the entire sponsor organization and provide training. Due to the support provided, the client was able to make a seamless transition to electronic documentation and maximize the capabilities of the new system to meet all its quality needs.

References

1 Phase Appropriate GMP for Biological Processes: Pre-Clinical to Commercial Production. Deeks T, Ed. Davis Healthcare International Publishing: Bethesda, MD, 2018.

2 Current Good Manufacturing Practice for Finished Pharmaceuticals. Code of Federal Regulations Title 21, Part 211. US Food and Drug Administration: Rockville, MD; https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cdrh/cfdocs/cfcfr/CFRSearch.cfm?CFRPart=211.

Lauren Schoukroun-Barnes, PhD, is a senior consultant; Dianne Cantara and Sarah DeDonder, PhD, are consultants; and corresponding author Dawn Speidel is a director, all at Latham BioPharm Group, a part of SIA Partners, 6810 Deerpath Road, Suite 405, Elkridge, MD 21075; [email protected]. The authors contributed equally to the development and technical acumen of this publication.

You May Also Like