Accelerated Pathways for Authorization of Medicines in Europe and the United StatesAccelerated Pathways for Authorization of Medicines in Europe and the United States

December 17, 2020

Before a medicinal product can be considered suitable for patients, it must go through laborious testing and cost-effectiveness analysis. In addition, all medicinal products must be authorized before they can be sold on the market and thus made available to patients (1). This is the case in the European Union (EU) and European Economic Area (EEA) countries as well as in the United States (US).

Before a medicinal product can be considered suitable for patients, it must go through laborious testing and cost-effectiveness analysis. In addition, all medicinal products must be authorized before they can be sold on the market and thus made available to patients (1). This is the case in the European Union (EU) and European Economic Area (EEA) countries as well as in the United States (US).

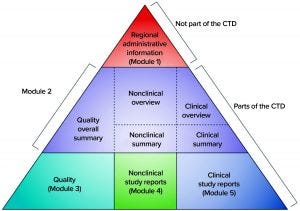

Every year, a number of medicines receive marketing authorization. In their wake, however, several thousand drug candidates fall by the wayside (2). The discovery and development journey through to approval and marketing (Figure 1) of successful candidates takes over 12 years (often much longer) and costs about US$2.6 billion (3–5). In fact, for every 25,000 molecules that start in drug-discovery laboratories, only 25 will be tested in humans, and only five will make it to market, with just one drug recouping its development costs successfully (1).

Figure 1: Drug development overview

Both the EU and US regulatory bodies require preclinical testing of drugs followed by three clinical trial phases and a final approval process. However, that process is expedited in the United States for some novel medicinal products through one of the US Food and Drug Administration’s (FDA’s) expedited programs (6–8). The expedited pathway applies only to certain therapies that treat severe or life-threatening illnesses and that are considered to offer potential therapeutic benefits beyond those of currently approved medicines. These US programs are

priority-review designation (PR) launched in 1992

accelerated approval (AA) launched in 1992

fast-track designation (FTD) launched in 1997

breakthrough-therapy designation (BTD) launched in 2012.

By contrast, the European Medicines Agency (EMA) has created five regulatory initiatives that expedite the approval process of such medicinal products in Europe (8–10):

conditional marketing authorization (CMA) launched in 2006

adaptive pathway, a pilot project that ran between March 2014 and August 2016

priority medicines scheme (PRIME) launched in 2016

accelerated assessment

authorization under exceptional circumstances.

Below, I review the types of therapeutics that are eligible to go through the US AA pathway and the EU CMA and adaptive-pathway approval processes, then provide an outline of the approval strategies for those programs. I focus solely on the processes that have been adopted in Europe and the United States. All other regions and approval pathways are outside the scope of this review.

Marketing Authorization Overview

All medicinal products need regulatory approval before they can be made available to patients. To that end, drug sponsors must apply for marketing authorization or product licensure — referred to in Europe as a marketing authorization application (MAA) and either a biologics license application (BLA) or new drug application (NDA) in the United States (6, 7, 11). The application includes information proving that the medicine has safety, quality, and efficacy characteristics that make it suitable for its envisioned use. Additional documents, samples of final product, and/or associated materials needed for final-product review may be included as well and described in the submitted application dossier.

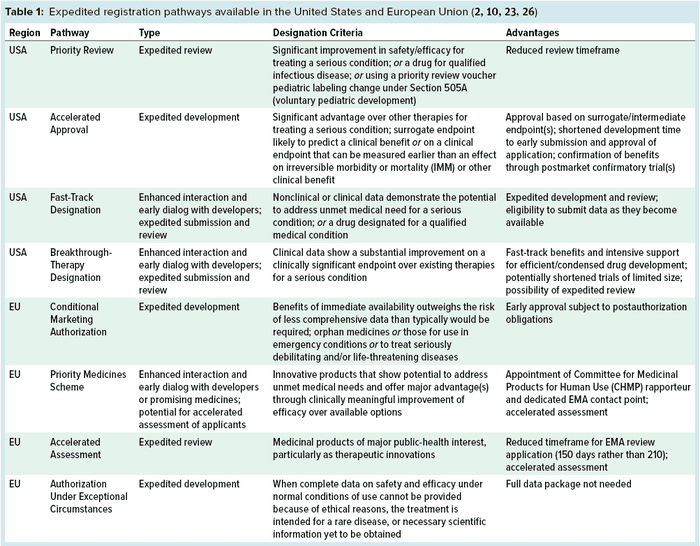

Figure 2: The five modules of the common technical document (CTD) (12)

Before 2003, dossiers for MAAs were structured according to different regional or country-specific specifications. However, since then, the US and EU regulatory bodies have requested that the format and contents of submitted dossiers follow the common technical document (CTD) format of the International Council on Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for the Registration of Pharmaceuticals for Human Use (ICH). The electronic Common Technical Document (eCTD) is a more recent electronic version (12), and Figure 2 illustrates its format. According to EU regulation, processing a submitted valid standard application takes 210 days: “The Agency shall ensure that the opinion of the Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use is given within 210 days after receipt of a valid application” (6). Moreover, clinical studies in Europe are conducted by EU member states, and drug-marketing authorizations follow a centralized, decentralized, or a mutual-recognition pathway. Meanwhile, clinical studies and marketing authorization in the United States are performed under observation of the FDA (13).

Before 1995, medicines were authorized in Europe through the 15 individual EU member states. For a company to obtain a marketing authorization, it had to submit an application to each member state where it wanted to market a given product. Drugs had to go through 15 separate review processes and receive 15 marketing authorizations (in the required languages) if they were to be sold throughout the European Union. The modern EU review and authorization process goes through a combination of federal bodies: the European Medicines Agency (EMA), national authorities of the EU member states, and the European Commission (EC). Both EU and national authorization systems are available, and the EMA sends recommendations to the EC (14).

Use of the EU authorization system is essential for a drug to achieve marketing authorization, whether in one or more member states or throughout the EU. Companies choose from three routes — decentralized, centralized, and mutual-recognition procedures — and selection depends on several factors, such as the type of drug to be marketed and the desired marketing strategy. But all US medicines are reviewed and authorized by the FDA (14).

Europe’s centralized pathway permits applicant drugs to be reviewed by the EMA and recommended to the EC for authorization. This route is necessary for medicinal products that address uncommon illnesses; widespread conditions such as diabetes and cancer; and infectious diseases such as acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) associated with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). Through the decentralized procedure, submissions for marketing authorization by the EC can be demanded by every member state concurrently. And in the mutual-recognition procedure, a drug is evaluated and assessed initially by one member state, the results of which can be used later to attain marketing authorization in additional member states. The latter pathway is standard for approval of generic medicinal products. Once a medicine is on the market, its safety will be monitored throughout the product’s lifetime through the pharmacovigilance system.

Expedited Access to Medicinal Products

The EMA and FDA share the same general goals of promoting public health, assessing the efficacy and safety of drugs, and working with specialists to improve product development. With those in mind, assessing the clinical benefits and potential threats of a novel drug can take many years (14). Mindful of that fact, the EU and US regulatory bodies have launched several initiatives to expedite the approval process for certain medicinal products. Table 1 summarizes these initiatives.

Europe’s adaptive-pathways route initiated through a pilot project that ran between March 2014 and August 2016. It is based on the EU approval methods described above, specifically the CMA approach that has been in operation since 2006.

The FDA Accelerated Approval Pathway: In 1992, the FDA launched its AA pathway to advance the approval process of certain treatments that would fill unmet medical needs and “that treat a serious or life-threatening condition and provide therapeutic benefit over available therapies” (6). This methodology permits authorization of a drug that exhibits an effect on a “surrogate endpoint” that can predict a clinical advantage or on an intermediate clinical endpoint that might arise sooner than the desired clinical effect. Those endpoints, however, may not be as solid as the endpoints used for routine drug approvals.

Surrogate endpoints are markers that directly determine beneficial outcomes of drugs. These include physical signs of how patients feel, function, or survive; laboratory measurements; radiographic images; or other supplementary measurements that are assumed to indicate a clinical benefit but do not measure it directly. Intermediate clinical endpoints are quantifications of therapeutic outcomes that are likely to predict clinical benefit, such as the influence of a drug on irreversible morbidity or mortality (IMM). Other therapeutic effects can be measured sooner than IMM effects, and drugs relying on those would go through traditional MAA procedures.

One example surrogate endpoint that proved successful in backing accelerated approval processes was elimination of bacteria from a patient’s bloodstream (as demonstrated by a laboratory measurement of bacteria in the blood) as a suitable measure to predict clinical determination of infection. With certain cancer types, radiographic imaging evidence was considered to be a suitable measure for predicting advancement in overall survival. An example intermediate clinical endpoint was implemented successfully in an AA process of a treatment for preterm labor. The drug was approved because it demonstrated a delay in delivery. In that case, postmarketing studies were required to prove enhanced long-term postnatal outcomes.

Adapting intermediate clinical or surrogate endpoints can save valued time in a drug-authorization process. The accelerated pathway is beneficial particularly when a drug proposes to treat a long-term illness that requires a long time for measuring its effectiveness. To date, in fact, this pathway has been used predominantly in cases when a targeted disease would have a long course, requiring an extended duration to assess and quantify the medicinal product’s clinical benefit. Instead of waiting to determine whether a medicine prolongs the life of cancer patients in clinical trials, for example, the US regulatory body can approve that drug based on an indication that it does diminish the size of a tumor, which can be assumed to predict the likelihood of an actual clinical benefit. Waiting to determine whether patients live longer would take much longer than waiting for tumors to shrink in size.

Since the AA pathway was introduced, several drugs have made it to market using this route. Between 2009 and 2013, the FDA approved 22 medicinal products for 24 indications through this pathway. Nineteen of those products were for oncology indications (15).

Every new drug in the United States since 1938 has been the subject of an approved NDA or BLA. When submitting the application, companies also must submit data collected during preclinical and clinical studies of the investigational new drug (IND). Part of the application to market a new medicinal product is conducted through form FDA-356h, “Application to Market a New Drug, Biologic, or an Antibiotic Drug for Human Use.” Expedited development approaches such as AA permit earlier submission and approval with datasets that may be less complete than those associated with standard development programs. Because the AA pathway affects clinical trial design and postmarket planning, drug sponsors are advised by the FDA to discuss the process with agency representatives during development (16).

Once a medicinal product receives market authorization and can be sold, the manufacturer must perform postmarketing (phase 4) clinical trials to monitor and corroborate its benefits. For example, oncology drug sponsors perform studies to prove that tumor shrinkage truly predicts extended life span for patients. The FDA will withdraw marketing approval if any of the following events occur (6, 7):

Trial outcomes fail to confirm the predicted clinical benefit

Evidence indicates that the drug is unsafe under its conditions of use

Product benefits are outweighed by potential risks

The manufacturer/applicant does not conduct required studies with due diligence or fails to abide by the postmarketing restrictions agreed upon

The medicine’s promotional materials (e.g., labeling and/or advertisements) are ambiguous or untrue.

Alternatively, the FDA no longer will require postmarket studies and/or will dismiss them if trials are deemed satisfactory for verifying a product’s clinical benefit. The medicinal product then would be considered suitable for approval under traditional procedures (6).

EMA Conditional Marketing Authorization: Under the CMA, drug candidates with promising but incomplete efficacy data are granted market authorization on the condition that they will be evaluated further while on the market (17, 18). In addition, specific obligations are imposed regarding collection of pharmacovigilance data (9, 19, 20). But this authorization is not intended to remain conditional indefinitely. The CMA is effective for only one year. Upon review of information collected during the conditional approval period, a drug could be withdrawn from the market, granted traditional standard approval, or continue to be marketed conditionally, depending on the results obtained during that period (17). The limit for submitting a renewal application is six months previous to marketing authorization expiry. Applicants are informed of the decision within 90 days of the EMA’s receipt of their renewal applications (21).

Companies seeking this form of expedited approval are encouraged to seek scientific advice before applying for accelerated assessment (2).

Conditional approval pathways in Europe typically are reserved for medicinal products that address life-threatening or extremely debilitating illnesses and orphan diseases. The EMA introduced CMA procedures in 2006 to cover products for which (11, 21):

The risk/benefit balance is encouraging

It is probable that complete clinical data will be available at some point

Medical needs will be met for conditions that have no other current treatment options.

When a company decides to apply for a CMA, it is advised to seek scientific guidance or protocol support from the EMA. Protocol assistance is a distinct form of scientific advice accessible to developers of designated orphan medicines. Applicants are advised to discuss their proposed marketing plans with EMA representatives six to seven months before submitting a marketing authorization application. An applicant also must inform the EMA of the intention to request a CMA and then submit a formal request when applying for market authorization. Furthermore, the agency encourages applicants to apply for accelerated assessment of all medicinal products that are considered to be suitable for conditional marketing authorization (2, 21). The Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP) assesses these requests, which determine associated postauthorization activities.

The standard process for evaluating a CMA is represented in Regulation (EC) No 726/2004 (8). However, applications for CMA might be subject to an expedited assessment process in accordance with Article 14(9) of that regulation, which reduces the application processing time from 210 to 150 days: “If the Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use accepts the request, the time-limit laid down in Article 6(3), first subparagraph, shall be reduced to 150 days” (8).

If a CMA is granted, requests, conditions, and exact deadlines related to it will be specified in the marketing authorization. Those requirements also are published as part of the European public assessment report (9). When CMAs are granted, they are limited to conditions in which only the clinical part of the application dossier (CTD) is less complete than normal. Partial preclinical or pharmaceutical data are accepted only when medicinal products are to be used in emergency situations or in response to a public health threat such as the COVID-19 pandemic.

If a CMA is not possible because comprehensive data cannot be obtained even after marketing authorization approval, then an exceptional circumstances authorization is granted instead. In this case, the authorization route does not lead to a traditional standard marketing authorization (8, 21).

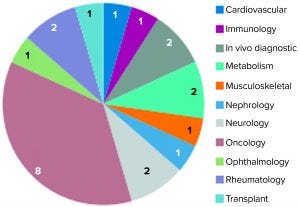

Figure 3: Unsuccessful conditional marketing authorization applications represented by therapeutic area (23)

In 2016, the EMA issued a report on 10 years of early access experience at the European Medicines Agency (22). According to this report, unsuccessful CMAs represented a diverse range of therapeutic areas, whereas the 30 successful candidates addressed just a handful of therapeutic areas — e.g., infectious diseases, neurology, oncology, and ophthalmology — and received CMA approval. Nearly three quarters (16) of 22 unsuccessful applications had orphan designations (22). In early 2017, and by the time that report had been published, 11 of the successful applications had been adapted into traditional standard marketing authorizations. Two were revoked for commercial reasons, and 17 remained as conditional approvals. Of all the CMAs granted, none were authorized for more than five years (23).

EMA Adaptive Pathways: This approach is not appropriate for all medicinal products. Specific preconditions must be met, such as the following:

• availability of precise endpoints for postauthorization decision-making of regulators and health-technology assessment (HTA) bodies — and, if relevant, fee payers

• limited access and control of prescriptions to ensure that a drug will be prescribed only to the patient population for which benefit/risk has been demonstrated

• specific checkpoints set throughout development for revision and adjustment of the process.

Figure 4: Eligibility requirements for medicinal products under EMA adaptive pathways (24); HTA = health-technology assessment; CMA = conditional marketing authorization

Figure 4 displays eligibility criteria set by the EMA for the adaptive pathway process. Through this program, a medicinal product follows an “iterative” process that is repeated until additional evidence can be collected and a desired outcome/endpoint is achieved. In such cases, the products are approved initially based on partial scientific evidence for use only in a limited group of patients who will benefit most from the treatment (10). Thereafter, and when more data become available, the product will be approved at a larger scale, both for the authorized indication and potentially further therapeutic uses. Note that the adaptive-pathways route is not a novel route of marketing authorization, but it in fact makes use of established regulatory tools.

In this approach, a medicinal product can be approved (as in the FDA’s AA process) on the foundation of a surrogate endpoint based on early data that confirms the benefit/risk balance of the medicinal product following conditional approval based on early data. Those data would be considered predictive of significant clinical outcomes and would need to be confirmed later with more clinically important outcome endpoints (24). Note that the adaptive pathways route necessitates collection of real-world data along with clinical-trial data that reflect the everyday use of a drug and should include discussions with key stakeholders such as HTA bodies and patients (2, 10).

The EMA’s pilot project target was to take six products through the parallel EMA–HTA advice route. Ending in 2016, this project was successful. Six of the 62 applications received progressed to a parallel regulatory–HTA scientific advice stage; a seventh progressed to formal scientific advice. In addition, 18 others were chosen for in-depth face-to-face meetings with the contribution of other stakeholders (10). The pilot program illustrated that such an approach could bring multiple stakeholders together: regulators, healthcare professionals, HTA bodies, and patients. In particular, this approach demonstrated the feasibility of supporting development of medicinal products in therapeutic areas with limited data such as Alzheimer’s disease, degenerative diseases, infectious diseases, and rare cancers (10).

In a 2015 study, Leyens and colleagues concluded that between the years 2007 and 2015, 25 medicinal products had received accelerated approval from the FDA and 17 had received EMA conditional approval (25). In both jurisdictions, most such approvals were in the oncology area, and most of the products were designated as orphan drugs. The resulting therapies were made available to patients who had limited alternative choices.

Patients Are the Priority

The extensive costs of current drug development, along with a shift toward more complex medicine, might indicate that in the future we will see decreasing stringency in drug development regulation and approvals through expedited pathways. Note that the main complication from using the expedited approval pathways such as those discussed above is the possibility of patient exposure to medicinal products that are not yet proven to provide a definite clinical advantage. In addition, these pathways allow for shorter and smaller clinical trials than the standard marketing authorization route. That limits the information available about delayed and/or uncommon side effects.

Therefore, the expedited pathways are not appropriate for development of all types of medicinal products. Many will continue to go through the long, traditionally intensive approval route. Success with the expedited pathways has enabled collaborative engagements between government bodies and other stakeholders, however, which could benefit all in the long term.

From my review of some FDA and EMA options, I recommend a more in-depth review and comparison of all available approval strategies before choosing one pathway. The regulatory agencies should collaborate together to streamline and harmonize their expedited approval pathways, as has been seen with other regulatory requirements through ICH efforts. Doing so would provide applicants seeking expedited approval with more opportunities for submissions worldwide using only one set of materials — ultimately increasing access for patients around the globe to the medicines they need.

References

1 Torjesen I. Drug Development: The Journey of a Medicine from Lab to Shelf. Pharm. J. 12 May 2015; https://www.pharmaceutical-journal.com/publications/tomorrows-pharmacist/drug-development-the-journey-of-a-medicine-from-lab-to-shelf/20068196.article?firstPass=false.

2 Regulatory Initiatives to Accelerate Market Access: UK, Japan, and USA Edition. Valid Insight Blog 5 May 2016; https://www.validinsight.com/regulatory-initiatives-accelerate-market-access.

3 DiMasi JA, et al. Trends in Risks Associated with New Drug Development: Success Rates for Investigational Drugs. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 87(3) 2010: 272–277; https://doi.org/10.1038/clpt.2009.295.

4 DiMasi JA, Grabowski HG, Hansen RW. Innovation in the Pharmaceutical Industry: New Estimates of R&D Costs. J. Health Econ. 47, May 2016: 20–33; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhealeco.2016.01.012.

5 Sullivan T. A Tough Road: Cost to Develop One New Drug Is $2.6 Billion; Approval Rate for Drugs Entering Clinical Development Is Less Than 12%. Pol. Med. 21 March 2019; https://www.policymed.com/2014/12/a-tough-road-cost-to-develop-one-new-drug-is-26-billion-approval-rate-for-drugs-entering-clinical-de.html.

6 Accelerated Approval of New Drugs for Serious or Life-Threatening Illnesses. Code of Federal Regulations Title 21, Part 314, Subpart H. US Food and Drug Administration: Rockville, MD, 1 April 2019; https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cdrh/cfdocs/cfcfr/CFRSearch.cfm?fr=314.500.

7 Accelerated Approval of Biological Products for Serious or Life-Threatening Illnesses. Code of Federal Regulations Title 21, Part 601, Subpart E. US Food and Drug Administration: Rockville, MD, 16 April 2019; https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cdrh/cfdocs/cfcfr/CFRSearch.cfm?CFRPart=601&showFR=1&subpartNode=21:7.0.1.1.2.5.

8 Commission Regulation (EC) No 726/2004 of 31 March 2004 Laying Down Community Procedures for the Authorisation and Supervision of Medicinal Products for Human and Veterinary Use and Establishing a European Medicines Agency. OJ L 136, 30 April 2004: 1; https://ec.europa.eu/health/sites/health/files/files/eudralex/vol-1/reg_2004_726/reg_2004_726_en.pdf.

9 EMEA/357981/2005. Guideline On Procedures For The Granting Of A Marketing Authorization Under Exceptional Circumstances, Pursuant To Article 14(8) of Regulation (EC) NO 726/2004. European Medicines Agency: London, UK, 2005; https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/regulatory-procedural-guideline/guideline-procedures-granting-marketing-authorisation-under-exceptional-circumstances-pursuant/2004_en.pdf.

10 EMA/276376/2016. Final Report on the Adaptive Pathways Pilot. European Medicines Agency: London, UK, 2016; https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/report/final-report-adaptive-pathways-pilot_en.pdf.

11 Directive 2001/83/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 6 November 2001 on the Community Code Relating to Medicinal Products for Human Use. OJ L 311, 28 November 2001: 67–128; http://data.europa.eu/eli/dir/2001/83/oj.

12 ICH M4(R4). Organisation of the Common Technical Document for the Registration of Pharmaceuticals for Human Use. US Fed. Reg. 82(190) 2017: 46078–46079; https://database.ich.org/sites/default/files/M4_R4__Guideline.pdf.

13 Kashyap UN, Gupta V, Raghunandan HV. Comparison of Drug Approval Process in United States. Europ. J. Pharm. Sci. 5, 2013: 131–136; https://www.hilarispublisher.com/open-access/drug-review-differences-across-the-united-states-and-the-european-union-2167-7689-1000e156.pdf.

14 Sifuentes MM, Giuffrida A. Drug Review Differences Across the United States and the European Union. Pharm. Reg. Affairs. 4, January 2015: e156; https://doi.org/10.4172/2167-7689.1000e156.

15 Naci H, Smalley KR, Kesselheim AS. Characteristics of Preapproval and Postapproval Studies for Drugs Granted Accelerated Approval By the US Food and Drug Administration. JAMA 318(7) 2017: 626–636; https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2017.9415.

16 Accelerated Approval. Friends of Cancer Research: Washington, DC, 2017; https://www.focr.org/accelerated-approval.

17 Gulfo J. The FDA Needs a Conditional Approval System. Forbes 5 May 2016; https://www.forbes.com/sites/realspin/2016/05/05/the-fda-needs-a-conditional-approval-system/#17ae3f349c7f.

18 Bonanno PV, et al. Adaptive Pathways: Possible Next Steps for Payers in Preparation for Their Potential Implementation. Front. Pharmacol. 8, 2017: 497; https://dx.doi.org/10.3389%2Ffphar.2017.00497.

19 Troncoso A, Diogene E. Dabigatran and Rivaroxaban Prescription for a Trial Fibrillation in Catalonia, Spain: The Need to Manage the Introduction of New Drugs. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 70(2) 2014: 249–250; https://doi.org/10.1007/s00228-013-1593-6.

20 Godman B, et al. Are New Models Needed to Optimize the Utilisation of New Medicines to Sustain Healthcare Systems? Expert Rev. Clin. Pharmacol. 8(1) 2015: 77–94; https://doi.org/10.1586/17512433.2015.990380.

21 Commission Regulation (EC) No 507/2006 of 29 March 2006 on the Conditional Marketing Authorization for Medicinal Products for Human Use Falling Within the Scope of Regulation (EC) No 726/2004 of the European Parliament and of the Council. OJ L 92, 30 March 2006: 6–9; http://data.europa.eu/eli/reg/2006/507/oj.

22 Messmer K, Hurley P. PRIME Turns One: PRIME and Other Early Access Tools. Evidence Forum 2017; https://www.evidera.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/PRIME-EMA-HTA-and-Early-Access-Initiatives.pdf.

23 Ribeiro S. Conditional Marketing Authorisation: Report on Ten Years of Experience at the EMA. European Medicines Agency: London, UK, 14 March 2017; https://ec.europa.eu/health/sites/health/files/files/committee/stamp/stamp6_cma_10_year_report.pdf.

24 Adaptive Pathways. European Medicines Agency: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/human-regulatory/research-development/adaptive-pathways.

25 Leyens L, et al. Available Tools to Facilitate Early Patient Access to Medicines in the EU and the USA: Analysis of Conditional Approvals and the Implications for Personalized Medicine. Pub. Health Genom. 18(5) 2015: 49–259; https://doi.org/10.1159/000437137.

26 CDER. Expedited Programs for Serious Conditions: Drugs and Biologics. US Food and Drug Administration: Rockville, MD, May 2014; https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/expedited-programs-serious-conditions-drugs-and-biologics.

Further Reading

A Look at the European Medicines Agency. US Food and Drug Administration: Rockville, MD, 9 August 2018; https://www.fda.gov/AnimalVeterinary/ResourcesforYou/AnimalHealthLiteracy/ucm246776.htm.

CDER/CBER. Guidance for Industry: Expedited Programs for Serious Conditions – Drugs and Biologics. US Food and Drug Administration: Washington, DC, May 2014; https://www.fda.gov/media/86377/download.

Chandanais R. A Look at the FDA’s Accelerated Approval Program. Pharmacy Times 16 November 2017; https://www.pharmacytimes.com/contributor/ryan-chandanais-ms-cpht/2017/11/a-look-at-the-fdas-accelerated-approval-program.

Development and Approval Process: Drugs. US Food and Drug Administration: Rockville, MD, 28 October 2019; https://www.fda.gov/drugs/developmentapproval

process/default.htm.

Eichler HG, et al. Adaptive Licensing: Taking the Next Step in the Evolution of Drug Approval. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 91(3) 2012: 426–437; https://doi.org/10.1038/clpt.2011.345.

EMA/531801/2015: Early Access to Medicines: Development Support and Regulatory Tools. European Medicines Agency: London, UK, 2016; https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/other/development-support-regulatory-tools-early-access-medicines_en.pdf.

Fast Track, Breakthrough Therapy, Accelerated Approval, Priority Review. US Food and Drug Administration: Rockville, MD, 23 February 2018; https://www.fda.gov/forpatients/approvals/fast/default.htm.

Sipp D. Conditional Approval: Japan Lowers the Bar for Regenerative Medicine Products. Cell Stem Cell 16(4) 2015: 353–356; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stem.2015.03.013.

Smith JA, Brindley, DA. Conditional Approval Pathways: The “Special” Case of Global Regenerative Medicine Regulation. Rejuven. Res. 20(1) 2017: 1–3; https://doi.org/10.1089/rej.2017.1932.

Shada Warreth is senior bioprocessing trainer and training coordinator at the National Institute for Bioprocessing Research and Training (NIBRT), Foster Avenue, Mount Merrion, Blackrock, Co. Dublin, Ireland; [email protected]; https://www.nibrt.ie.

You May Also Like