Won't Get Fooled AgainWon't Get Fooled Again

The world loves a winner, and no one wants to be linked to a failed endeavor that could stall or otherwise negatively affect his or her career. If you’re reading this magazine, you’ve probably been inspected or audited by regulators and/or customers at some point.

When it was finished, did your company compare favorably with expectations, or did the reports reflect a negative image?

Did they mirror management’s view of operations, or was there a disconnect with management perceptions?

Did the results generally show things in a worse light than what reasonable expectations would indicate?

Consider for a moment that regulatory inspections and corporate audits are somewhat like a high-school football game, one that regulated companies are obliged to play whether they want to or not. This game is always played on the inspected party’s “home field” and the auditors/inspectors are always the visiting team, but there is no home-team advantage. The date and time of the game is dictated by the visitors for their advantage, and the specifics and the length of play are entirely at their whim. Furthermore, the visiting team is allowed without announcement to bring as many players as they want to “the game” and wander through the home field without disclosing the specifics of their agenda until well after they have collected needed information. And there are no referees on the field.

Zero Sum

In an earlier work, we characterized regulatory compliance as a competitive team activity that created value reflected in the bottom-line accounting of company profitability (1). We observed that champions earn freedom to operate for their companies whereas losers are enjoined, have products seized, and/or are prosecuted for their (mis)deeds. We then described a systems approach to practices that could increase an inspected party’s preparedness to play.

I’ll tip my hat to the new constitution,

Take a bow for the new revolution,

Smile and grin at the change all around me,

Pick up my guitar and play

Just like yesterday,

And I’ll get on my knees and pray:

We don’t get fooled again.

—Peter Townsend

(The Who, Who’s Next)

The impression that we may have unintentionally left with the reader is that the “competition” was a game like baseball with winners and losers — or maybe combat, in which one fighter lives and the other dies. Indeed, our earlier references to Sun Tzu’s book, The Art of War, in regards to defense of the supply chain could lead to that conclusion (2). But that was not our intent. That would define a zero-sum game like poker, in which player A wins $5 and player B loses $5. If we add the two together, +$5 and –$5, we get a sum of 0. Any game with winners and a losers is most likely a zero-sum game.

Inspections on a level playing field need not be zero-sum games. After all, what is the inspector’s win or loss relative to the inspected? The regulator wants a safe, efficacious product with an appropriate pedigree coming from the plant; the company wants freedom to operate. If everything is in order, then the inspector says “Thank you” and leaves. The plant wins, but the regulator does not lose unless he or she faces some kind of directed outcome or quota of findings that must be met. When discussion ensues — and it always will — the conversation should be more of a learning experience in which an inspector becomes familiar with the application of technologies to specific product-related nuances, and the inspectee learns the nuances of regulatory (or other) expectations. Theoretically, both parties win when product for sale to the public is improved — and aren’t regulators members of the very same public that they serve? The truth is that one-sided wins and losses are generally the result of poor gamesmanship, either in preparation or in execution. The other type of game, the type we really play, is a nonzero-sum game. The sum of participant outputs does not equal zero, and both players may actually win something.

Ode to Math

Inspections can be considered a game in the mathematical sense. There is a conflict of interest among n individuals or groups (players), and there exists a set of rules that define the terms of their exchange of information and pieces, the conditions under which the game begins, and possible legal exchanges under particular conditions. The entirety of the game is defined by all moves up to that point, leading to an outcome. Consequently, game theory (mathematical analysis of a conflict of interest to find optimal choices leading to desired outcome under given conditions) can be a useful tool here.

Game theory is a complex assemblage of many branches of mathematics, including set theory, probability and statistics, and plain old algebra. Inspections are dictated by a given set of rules that can be used to outline a set of possible moves, which can be ranked according to desirability and effectiveness. With available information, such a set can be constructed for both player and opponent, thus allowing predictions about possible outcomes given a certain number of moves with a probabilistic accuracy.

Those “moves” are defined by the rules of the game and either can be made in alternating fashion, can occur simultaneously for all players, or can be made continuously by a single player until he or she reaches a certain state or declines to move further. Surprises that result in one-sided “wins or losses” (e.g., warning letters, consent decrees, recalls, and discontinuation of contracts) are generally the result of poor gamesmanship because some players are ill-prepared or not properly equipped for the game. Sometimes, surprises are less so than they are simply the result of risky bets.

Skilled inspectors can pick-up on mendacity and distrust at companies from ordinary observation and social cues — such as interpretation of body language, confidence, and the quality of answers — to gauge the relative strength of their defensive positions and focus efforts specifically on the weakest areas. Likewise, skilled managers will pick up on duplicity in an inspectors approach when an inspection goal is different than stated. Astute players can apply game theory to verify the level of trust and/or strength in an opponent. Using a familiar construct, a variation on the classical “prisoner’s dilemma” can be easily configured and inserted into the dialogue to evidence cooperation or lack thereof.

The Prisoner’s Dilemma: Two suspects are arrested by the police, but the police have insufficient evidence for a conviction of either. Having separated the prisoners, they visit each one to offer the same deal. If one testifies for the prosecution against the other (defects) and the other remains silent (cooperates), then the defector goes free and the silent accomplice receives the full 10-year sentence. If both remain silent, both prisoners will be sentenced to just six months in jail for a minor charge. If each betrays the other, then each receives a five-year sentence. So each prisoner must choose whether to betray the other or remain silent. Each is assured that the other will not know about the betrayal before the end of the inv

estigation. What do they do?

If we assume that each player cares only about minimizing his or her own time in jail, then the prisoner’s dilemma forms a nonzero-sum game in which two players may each either cooperate with or defect from (betray) the other player. As in most game theory, the only concern of each individual player (prisoner) is maximizing his or her own payoff, without any concern for the other player’s payoff. The unique equilibrium for this particular game is that a rational choice leads both players to defect, even though each one’s individual reward would be greater if they played cooperatively. Skilled players, however, always consider the overall impact of their actions.

Rules of the Game

The very first rule of all competitions is etiquette. Even prize fighters shake hands before pummeling one another. Good manners breed cooperation; bad manners force individuals into distinct roles. On television, Detective Columbo (Columbo) never threatened or forced information from his suspects, and Jim Phelps (Mission Impossible) always accomplished his impossible mission by letting the bad guys make their own mistakes. Even Andy and Barney (The Andy Griffin Show) caught bad guys while keeping their bullets in their pockets.

The most important rule in the inspection game is ethics, which constitutes a conundrum on this particular playing field. Despite corporate codes of conduct designed to prevent, detect, and punish legal violations, many managers still place ethics in the personal conduct domain. They remain a confidential matter between individuals and their consciences unless unethical conduct could somehow receive public disclosure. Individual ethics, in such cases, have nothing to do with management beyond abstaining from illegal practices.

In truth, however, ethics has everything to do with management, especially for the pharmaceutical industry, in which personal responsibility is a hallmark of the Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act (3) and reflects a core value of FDA compliance and enforcement policy. In the agency’s eyes, individuals actively participate in unlawful conduct, allow it to happen by passively tolerating violations, or fail to take steps to learn that violations are occurring. Strict liability ensues when the law presumes that an inspectorate is acting in good faith. In some cases, however, courts allow regulators to engage in “sting” operations and use entrapment as a tool while mandating good faith of the inspected under penalty of law. To the FDA’s credit, this falls well outside of routine and would conceivably only be used when conduct is egregious and/or public safety is truly deemed at risk. And court supervision is mandated to guide the process because public confidence is too important to risk for inconsequential gains.

Most managers are compelled from time to time, in the interests of their companies or themselves, to practice some form of deception when negotiating with customers, unions, government officials, or even other departments within their companies. By conscious misstatements, concealment of pertinent facts, exaggeration, or bluffing they seek to gain advantage. It is probably fair to say that if someone refuses to bluff and feels obligated to tell the truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth, then that person is ignoring certain opportunities permitted under the rules and is thus at a heavy disadvantage in the business environment.

Regulators have a clear advantage in bluffing or even threatening as a strategy. They do, after all, hold the trump card when it comes to sanctions. They have an established hierarchy with a large enforcement wing to coerce cooperation. If that fails, then they have the direct line to district attorneys and US marshals. It thus becomes necessary to evaluate threats as either plausible or implausible. Game theory again offers a model: a mad bomber confronting someone in an elevator.

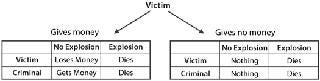

The (Mad?) Bomber: The criminal demands money, threatening to blow himself and the victim up unless he gets it. This game is reasonably straightforward: The victim has two options (pay or refuse to pay), so the game tree would look like Figure 1. In a rational scenario, the victim should choose to keep the money. The assumption is that the criminal is ultimately rational and will choose to live rather than die, thereby eliminating the detonation consequences and forcing a repetition of the demand such that successive iterations will produce the same result.

Figure 1: ()

No one should expect the ethical principles preached in churches to be applied in a game scenario. Indeed, it is right and proper in a game of poker to bluff a friend out of the rewards of being dealt a good hand. Players should have no remorse when — with nothing better than a single ace in hand — they take the pot from someone holding a superior hand. Bluffing is a form of lying, but characterizing that lie is subject to values, morals, and context. Would anyone believe, “Of course, I’ll respect you in the morning” to be an affirmation of undying love?

Typically, unethical practice involves tacit (if not explicit) cooperation of others and reflects the values, attitudes, beliefs, language, and behavioral patterns that define an organization’s operating culture. The basis of private morality is a respect for truth, so the closer someone comes to the truth, the more he or she deserves respect. Ethics in business are as much an organizational as a personal issue. Managers who fail to provide proper leadership or institute systems that facilitate ethical conduct share responsibility with those who conceive, execute, and knowingly benefit from corporate misdeeds. And managers exist both in corporations and in government.

The globalization of business complicates and exacerbates this field of play. Different cultures, societies, languages, and sometimes national objectives confuse perceptions and interactions between and among players. Sometimes politeness dictates that you agree with your distinguished visitor even if he is wrong. The lack of a plural you in English sometimes confuses the interpretation from collective to singular. Indeed, it even confuses Americans, or we wouldn’t have the collective y’all commonly used below the Mason-Dixon Line. The interpretation of a lie can vary depending on who you’re talking to and your reasons for misrepresenting the facts. Some religions even grant exceptions for individual circumstances, and not everyone believes in consequences such as eternal damnation as punishment for bad deeds in life.

The Playing Field

Regulatory inspections challenge everyone, including the inspectors. An inspector may know what the next question will be, but the multitude of answers and the permutations and combinations of responses ensure that no two inspections are ever the same. Despite their best intentions, inspection managers often end up managing the both inspectors and respondents when they should be managing the process itself (playing the game and strategizing the next move with mathematical risk analysis). A well-managed process seemingly makes an inspector more effective and more efficient, which makes the outcome more constructive for everyone. So the more effectively an inspe

ctor can perform his or her job, the faster he or she will finish, minimizing misunderstanding-based consequences to the company and making inspection results more predictable. And a well-managed process provides at least some control and advantage to the inspected party.

The biopharmaceutical industry works under the presumption that this game is fair, but we must recognize that regulators have resources, police powers, and nearly unlimited time. In theory, they could be arbitrary and capricious in their execution, if they so chose. Customers can also enter the game with predetermined outcome objectives. A government inspector has a predetermined strategic advantage in the opening volley. He or she starts the process and defines its parameters and scope within the boundaries of an interpretive set of rules, retaining the power to set the time/schedule and the ability to end the game at his or her discretion. A customer has some initial control but necessarily works within some constraints: a limited ability to see beyond the subject product and a limited time within which to work. Nevertheless, from that moment on, both teams will analyze every situation and effect an interplay to achieve similar, opposed, or mixed interests.

A critical task facing inspection managers is enabling and facilitating appropriate communication. This is where the proverbial rubber hits the road: the human interface. Typical inspection plans often include the use of a “shadow room,” where documents requested are reviewed and designated experts are prepared to go before an inspector. The efficiency and effectiveness of an inspection team and shadow room personnel ensures that order is brought to the inspection. A timely and accurate response creates a favorable impression of cooperation and well-controlled quality systems (4). But the process can quickly become unmanageable if an inspector’s request requires someone to run to the shadow room, order up some information, and return to the inspection team. If the shadow team has some problem finding that information, they have to run to the inspection team, talk to the person who requested the material, and coordinate an accommodation modality. All of that occurs under the watchful eyes of the inspector: people running back and forth, phones ringing, and so on, with everything being exacerbated by the internal mandate to accurately record and document the proceedings.

Humans are generally not very good at solving nonzero-sum games when an optimal strategy requires more than one action. We usually tend to regard our opponents as enemies until proven otherwise, which restricts our strategy. That can hinder our understanding of the cooperative intentions of other participants. Even if one player thinks of the cooperative strategy, it is difficult to communicate that by actions (plays) alone. There many hills to be climbed for these dilemma problems to be overcome. Winning — or not losing — requires intimate knowledge of the rules, insight into the psychology of the other players, Oscar-winning acting skills, total self-discipline, and the ability to respond swiftly and effectively to opportunities provided by chance.

It’s About Trust

Inspections and audits are a game that industry can’t afford to lose. Although the game is stacked in favor of the opposing side, measures must be taken to play your best. Athletes train hard to prepare themselves for events. Teams train together and practice to achieve a level of optimal performance. Coaches work with their players and strategize: Good ones know how to pit their players and teams against the opposition by playing strengths to weaknesses and massing strengths at appropriate times. They adapt to the dynamics of the moment. Coaches must focus on the players and plays rather than underlying facilities, systems, and activities that make up the playing field.

BEFORE, DURING, AND AFTER

Before the Inspection

Study the rules of the game. Fouls and penalties can be found in other companies’ records (e.g., 483 observations, warning letters, and consent decrees), at meetings and seminars, and in the press.

Review past game records. Weaknesses from your last game with this particular group can and will be exploited in your next game.

Don’t disable your players with unrealistic objectives such as “no observations.” This precipitates a variable play that detracts from the real objective.

Have your team members’ options and roles predetermined and prerehearsed.

Know your weaknesses and limitations, and work on strengthening them.

Practice what you will be playing (mock FDA audits, follow-up lists, and so on).

Ensure that everyone understands this will be a team win or loss. Outstanding individual performances on their own cannot preclude a loss.

Get coached. Consultants should be called to preclude problems rather than fix them after the fact.

During the Inspection

Play both defense and offense. Inspectors and auditors can make wild requests, and if you accede to them completely, you open the door to inquiry beyond what is required.

Document — with a noninvolved scribe if possible.

Be ready to substitute new players to key positions and special teams.

Wrap up each day by reviewing accomplishments/discoveries and planning for subsequent activities. This ensures readiness and precludes miscommunications.

Meet for prearrival readiness and postdeparture wrap-ups with extended home-team staff.

Involve and debrief top management.

After the Inspection

Consider responding early.

Fix cited problems and report.

Hire consultants or new staff if local resources are insufficient.

Plan and perform lessons-learned exercises.

Falsehood ceases to be falsehood when it is understood on all sides that the whole truth is not expected. So we must not let inspections devolve to the analogy of the criminal court, in which a criminal is not expected to tell the truth when he pleads “not guilty.” Everyone from the judge to the jury to the court reporter takes it for granted that the job of the defendant’s attorney is to get his client acquitted, not to reveal the whole truth, and this is considered ethical practice. We shouldn’t be looking for the kind of technicality that sets a criminal free.

Lastly, all people involved in an inspection should always remember that their livelihood and the livelihood of their industry is based on trust. The simple idea that you can buy a relatively nondescript white tablet that when taken will actually make your health better is somewhat a matter of faith in itself. Customers must believe that everyone involved in the chain of research, production, distribution, and regulation of those pills (patches, inhalers, or injections) has done his or her job well. Consumers typically have no personal way to verify that a medicine is what it is purported to be rather than a life-threatening poison. In an inspection, if either the inspectors or the inspected fail that consumer trust, it places the entire industry at risk. On a personal level, we all know someone who requires the benefits of the drugs we make.

About the Author

Author Details

Corresponding authors Joseph F. Noferi Esq. and Ralph L. Dillon are managing directors at Compliance Surety Associates, [email protected]. Internationally they have been managing groups, projects and portfolios to mitigate quality and regulatory risk for over 30 years. Success is measured by non-events in inspections.

REFERENCES

1.) Noferi, J, and R. Dillon. 2008. Effect-Based Compliance: The Next Frontier in

Strategic Management. BioProcess Int. 6:18-23.

2.) Noferi, J, and R. Dillon. 2009. Defending the Supply Chain: Lessons from Sun Tzu. BioProcess Int. 7:10-17.

3.)US Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act: www.fda.gov/RegulatoryInformation/Legislation/FederalFoodDrugandCosmeticActFDCAct/default.htm.

4.) 2003. Managing the Inspection: Exploring New Technologies. Focus 8:26-28.

You May Also Like