Lean Six SigmaLean Six Sigma

December 1, 2012

About 10 years ago as a vice president of Avecia Biologics, I wrote an article for an early issue of BioProcess International looking ahead at likely changes in biomanufacturing (1,2,3). For the best part of the intervening period, Avecia Biologics and Diosynth slugged it out in the marketplace, each trying to grow its contract manufacturing business at the expense of the other. But in a life-altering two-year period between 2009 and 2011, both companies saw their realities and perspectives change:

Schering Plough acquired Organon, the corporate owner of Diosynth.

Merck/MSD acquired Avecia Biologics.

Merck/MSD and Schering Plough merged, bringing Avecia Biologics and Diosynth under the same corporate ownership.

Fujifilm acquired the two CMO businesses from Merck/MSD, brought them together, and challenged them to operate as a single truly global contract manufacturing organization (CMO).

Thus in April 2011 Fujifilm Diosynth Biotechnologies was born, with the Diosynth name retained to reinforce Fujifilm’s long-term commitment to the CMO business. It has been an interesting experience to bring two similar competitors together and get them to operate as one effective business. Faced with the question of how to bring this about, we decided to seek some common denominators. Both businesses had already adopted the “lean six sigma” (LSS) concept as a catalyst for driving business change and improvement, so we had our first point of overlap.

A Decade of Change

The past 10 years has seen many changes both in the biopharmaceutical marketplace and in biotechnology, which has proposed continual challenges for all companies seeking to create and operate manufacturing processes that enhance value rather than detract from it. Much commentary has been given to monoclonal antibodies (MAbs), but the world outside MAbs has some fresh challenges as well.

First, the markets and diseases targeted by biologics are becoming more tightly defined and focused, which enables the exquisite specificity of biology to be fully exploited. As a result, smaller volumes of product are needed. The personalization of medicines is widely discussed, with many new products complemented by diagnostic tests, so the move to lower product volumes is almost certain to continue.

Similarly, biopharmaceutical products themselves seem to be getting more potent. This trend has two effects: a reduction in expected volumes needed and an increasing need to show complete cleaning of multiproduct facilities. With the exception of some very large-volume biologics, multiproduct facilities appear to be the growing norm. Indeed, this is one area in which regulators in both Europe and the United States are showing increasing focus. The next few years are likely to reveal new insights and approaches to managing the change from one product to another.

The advent of disposable, single-use bioreactors is having a transformational effect on products derived from mammalian cell culture and provides a neat solution to some related issues. I expect the impact on microbial-derived biologics to be much smaller, however, if the cost-of-goods benefits derived from intensive microbial processes are to be retained.

Avecia 2004 ()

Business strategies of companies developing biologics have also evolved. Ten years ago, for those of us selling CMO services, price wasn’t seen to be a major question. How things change! In the biotechnology community, for which funding is tight and often provided in small increments, timely delivery of programs has become vital, with drug developers increasingly seeking options to shave even a few days off their product timelines. So CMOs need to focus on aspects such as the time from completion of manufacture to quality assurance (QA) release of product.

The current financial climate presents another difficulty for this sector in the need to offer ever more flexibility in program management. Stop-and-start is a frequent requirement, so being able to introduce a new process quickly into a current good manufacturing practice (CGMP) asset with short notice is becoming a necessity. So often in such situations, the supply chain is rate limiting. It can be quite surprising how long procurement of resins and some other commonly used raw materials can take, adding noticeably to an overall program timeline. Although MAb manufacturers can delight in a commonality of materials used, the sheer diversity of microbially derived biologics can make each new product bespoke. So it’s a brave (and probably unemployed) supply chain manager who holds sufficient inventory for all eventualities.

Considering all those issues together brings up two simple questions: How do we achieve more flexibility with faster program delivery? And how can we develop and operate complex processes cost-effectively?

As a CMO, Fujifilm Diosynth Biotechnologies relies on winning business from often hard-pressed customers. The company has been addressing change as a fundamental business reality from its early days, when Avecia and Diosynth operated separately with LSS in their respective tool kits. Fujifilm itself is justly proud of its high-quality manufacturing heritage, in which lean methodology has been (and remains) central to continuous improvement. So the Fujifilm ownership has served to redouble our efforts to reinforce this lean approach. A couple of positive developments and improvements are worth highlighting below. It’s often simple things that make the biggest difference.

Communication Is Key

Recognizing that a problem exists is one thing, but then communicating that problem to the right people is quite another. In a complex CMO business, priorities can change from day to day. As mentioned above, customer needs can also change daily. Cross-functional input and effort is almost always needed, yet there are many ways by which information can be passed or missed: hallway conversations by the coffee machine, monthly meetings, and the ubiquitous emails that so often can be overlooked in our daily inundation of data.

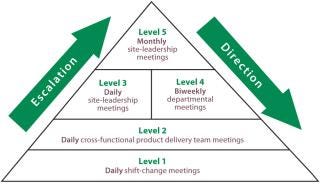

A structured and visual communication process is essential. It was certainly transformational for our CMO business when the company adopted metrics and charts that make issues visible. A tiered series of meetings — from daily cross-functional product and milestone delivery teams up to the monthly business leadership (Figure 1) — enables common understanding and provides visibility of issues to those people best able to address them, who can be at very different levels in an organization. This may not always be an easy message to receive, but involvement of senior management can sometimes exacerbate a problem rather than help to provide a solution.

e=’float:left;margin-left:0px;margin-top:5px;margin-right:0px;margin-bottom:7px;background-color: #f7f7f7;width:auto;’>

Figure 1: ()

Shortening Manufacture-to-Shipment Timelines

An important change came in our business when it began to focus on reducing the time from a product’s date of manufacture to shipping a released active pharmaceutical ingredient (API). One specific product was averaging over 200 days, but with wide variability. That had negative consequences for timely delivery and inventory management. It seemed that the only way the company could achieve a 100-day average would be through making overtime work routine, which was often vital to hitting critical deadlines.

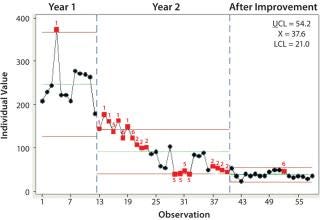

Using lean methods, the problem was analyzed — with much-appreciated help from “sticky notes” and brown paper as well as engagement of all practitioners. The team highlighted areas in an 83-step process for batch release with rework loops, multiple hand-offs, and information arriving out of sequence (making people wait before they could act). A redesign resulted in a 62-step process — 30% fewer steps — with sequenced information flow and elimination of document bundling through the review process. Critically, this was a joint exercise with the customer. Over a 12-month period, we drove the average time down to a consistent 38 days (Figure 2).

Figure 2: ()

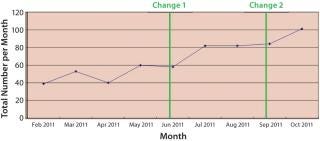

Figure 3: ()

LSS in R&D?

A major challenge for CMOs is rapid translation of a manufacturing process from research and development (R&D) to CGMP compliance. This was a particular issue in 2010 for one very complex process in which the standard work sequence we used involved a two-month delay beyond the target fill–finish date for start of a phase 3 clinical trial. Analysis of the problem highlighted how, over time, our drive to improve quality compliance had led to incremental changes that created a complex vortex with poor sequencing of activities, multiple hand-offs, too many steps, and too many different groups involved. The LSS approach brought high process visualization, better sequencing, more parallel activities, and better communication — with a subsequent 50% reduction in duration for introduction and qualification lead time. That enabled our customer to hit its milestone for beginning the phase 3 study in 2011, which is still under way.

Manufacturing is a natural place for LSS approaches. Applying them in an R&D environment is an altogether different challenge in which, to be polite, the cultural fit with such methods is not quite so obvious. Developing microbial fermentation processes does demand use of expensive equipment, and we need to match the intensity of Escherichia coli with our own resource use.

In 2011, we faced demand that outstripped capacity in our development fermentation facility, which could have delayed programs and reduced revenue. The traditional approach to buy more fermentors would not appeal to us even without the long nine-month lead time. So we applied the same approach as above for manufacturing operations, but with the extra need in R&D to reinforce a “burning platform” mentality and belief in a need to change. R&D staff do respond to business challenges, so implementing tier meetings and visual management were the first changes made — and that gave immediate results. Next, the company focused on addressing change-over times with a much better approach to planning. The outcome: a step change over a six-month period from 40–50 runs/week to 80–100 runs/week. Output performance has continued to improve over time.

Coming Together As One

Those three examples show how LSS has helped our CMO business to improved, increased its ability to respond flexibly and provide benefits to its customers. LSS continues to be a bedrock of our business, with a business objective for >80% of all staff to be involved in LSS activities (including commercial groups, who can present an even bigger challenge than R&D).

And one other vital benefit has come from this work. It’s about bringing together two former competitors and getting them to work as one. Both Fujifilm Diosynth businesses and sites — in Billingham, UK, and Research Triangle Park, NC — speak the same LSS language, share training and development, and address similar problems. And we have found the engagement and marriage to be happy and productive. This allows the experiences and track records of both sites to combine and enhance the company’s ability to continue to change and meet the evolving expectations of regulators and customers alike.

About the Author

Author Details

Dr. Stephen C. Taylor is commercial vice president of Fujifilm Diosynth Biotechnologies, Belasis Avenue, Billingham, TS23 1LH, United Kingdom; 44-16423-64001, fax 44-16423-64463; [email protected]; www.fujifilmdiosynth.com.

REFERENCES

1.) Taylor, SC. 2003. The Real Biomanufacturing Capacity Crisis: Stainless Steel or Flesh and Blood?. BioProcess Int. 1:30-34.

2.) Taylor, SC. 2005. We Need to Get on Their Radar. BioProcess Int. 3:88.

3.) Taylor, SC. 2006. The Development Journey: CMOs As Traveling Companions. BioProcess Int. 4:S18-S20.

You May Also Like